Notes on the Hockney-Falco Thesis, and “Tim’s Vermeer”

In one recent week, three separate people recommended the movie “Tim’s Vermeer” to me, so I finally watched it. Then I finally got around to reading David Hockney’s Secret Knowledge (well, just the first half), which my co-advisor Ken Perlin had generously given me as a graduation gift twenty years ago. As I’ve dug deeper into the question of whether the Old Masters “cheated,” the literature and the topic seem complex, and I don’t care enough to study it enough to form a serious opinion. But there are some fascinating aspects that connect to ever-interesting questions about the relationship between painting and photography, both visually and historically.

Here are few thoughts on the Hockney’s Secret Knowledge and “Tim’s Vermeer.”

Is Hockney right? And did Vermeer paint like Tim?

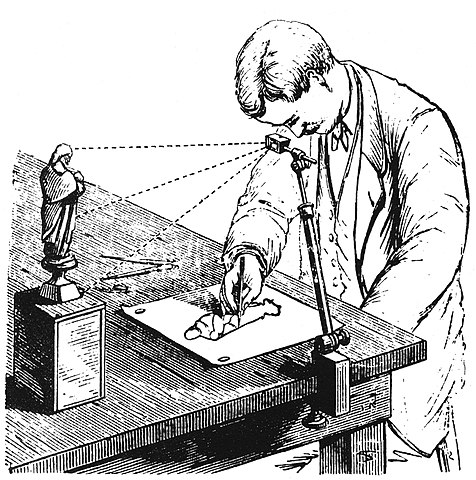

It’s now called the Hockney-Falco Thesis: the Old Masters used optical aids to help painting, and that these aids have been largely unknown or secret over the centuries. Hockney often discusses the camera lucida, which uses a mirror to superimpose an image of a scene with a paper or canvas, and spent a year drawing portraits with one. (You can buy modern versions online.)

The consensus of the art historians I’ve read seems to be that this thesis could be true in some cases, but, as there is no primary evidence whatsoever, it’s unverifiable at best. It’s more plausible for more-recent artists, as optics improved and became more widespead. It’s very likely that, in the 19th century, Ingres used photographic and optical techniques (a claim made by Aaron Scharf long before Hockney), whereas it’s much more that iffy whether Vermeer did, since he worked at a time when optics were rare and primitive.

I think Hockney makes some persuasive arguments, but his claims are not particularly scholarly; he cherry-picks information wildly, and makes wildly overconfident assertions that some bit of drawing “must” have been done optically. He’s better at proposing an intriguing hypothesis than at evaluating it rigorously.

Likewise, “Tim’s Vermeer” throws around all sorts of questionable assertions, like the inane one (included in the trailer above) that “this falloff of light is something that an artist cannot see.”

For some reading on the Hockney-Falco Thesis, check out this debunking of “Tim’s Vermeer” by Stork et al., this 2001 discussion site, and the book Hockney’s Eye. And there’s also this upcoming Dutch reality TV show in which amateurs and experts compete to recreate Vermeer paintings.

Can you tell if a drawing came from a photo?

Hockney’s theory began when he attended an exhibition of Ingres drawings, which struck him as looking like drawings made from photographs. He points to many other examples of artworks, arguing that they show telltale signs of optical assistance.

In a sense, he is saying that: a picture made from a photograph (or other optical aid) looks different from a drawing made from life. And, you can tell by looking at it. This, to me is a fascinating claim. Can you tell if a picture was made from a photograph? If so, how?

Few of the historians I’ve read spend much time on this part of his argument. Which seems natural, since it seems so hard to tell just by looking, very hard to verify his claims.

Here’s a separate blog post about the question of whether you can tell.

Backlash

When he introduced his thesis, Hockney received some backlash from those who revere the Old Masters. In part it challenges the notion of the Old Masters as artistic geniuses, giants who walk the Earth no more. But it also reflects the kind of backlash given to all technologies that automate some aspect of art; the only difference is that it’s retrospective. That is, it’s a form of the myth that great art requires great skill, and that, somehow, pointing out techniques that these artists used is an attack on their skill.

I appreciate Tim’s idea that Vermeer was more of a tinkerer than “just” an artist, like many other significant artists throughout history who tinker and experiment with technology, and ignore artificial distinctions between art and science.

Hockney mentions that Michaelangelo thought the then-new technology of oil painting was for “amateurs,” because it wasn’t as difficult as fresco. Status Quo bias seems to be a constant in how people view new kinds for art.

Artisans

This debate seems like a prime example of why it’s important to know why the pre-Romantic notion of “art” was very different from our own. Our modern concept of “artist” arose in the Romantic era of the 17th and 18th centuries. To put it in simple terms, people like Vermeer and Caravaggio wouldn’t think of themselves as “artists” in our modern sense, more like “artisans.” Their works were extraordinary, but our Romantic notions of artistic genius would have been foreign to them. Most famous pre-Romantic Western art was work-for-hire, commissioned by a church to fill a spot in a nave or by a wealthy person for a wall of their house. Workers hired to do a task aren’t going to get hung up on notions of “genius” and “cheating” the way a modern artist or critic might. Using optical devices likely wouldn’t have been “cheating.”

Moreover, it would have been common, for many older artists, to have assistants and apprentices in the studio help out with the painting. If you bought a painting from Raphael’s studio, there was no guarantee or expectation that Raphael painted every stroke; it’s not clear that anyone cared, as long as the painting did its job.

Stork and others question: why would Vermeer have undertaken such a laborious and difficult drawing procedure? One answer could be: because it’s easier to delegate work to apprentices. Tim’s process was pretty mechanical; it wouldn’t have been hard for him to sketch out the plan and then hire assistants to do a lot of the more repetitive work.

Hockney also doesn’t claim that these artists drew every stroke this way. For example, he suggests that Caravaggio sketched out the painting using an optical device, and then completed it at his leisure later. This makes a lot of sense to me and I’ve done often done something similar with my own experiments with photography.

Does it matter?

Who cares?

Personally, I find these ideas a little empowering.

When I started drawing and painting again, I had an idea that working from photographs was “cheating”. Making art is often an emotional rollercoaster, full of self-judgments and self-doubt. We’re taught to revere genius artists and to devalue our own work in comparison (“is it really art?”). Knowing that many of the Old Masters might have used optical technologies too just gives more reason to think that it’s “ok” to use whatever techniques you need to. There is no “cheating” (apart from actively deceiving an audience.)

I think that making art should be accessible to everyone. Putting the Old Masters on a pedestal, as supreme geniuses, impedes our appreciation for new forms of art, and prevents people from learning to make their own art. Lots of people say “I can’t draw” and “I haven’t got talent,” and understanding the processes and techniques involved can help.

In one video about Kehinde Wiley’s work, his colleague says: “Oftentimes I read ‘Wiley’s work reference master paintings.’ I think that’s actually wrong. I think Kehinde Wiley has mastered master painting.” The implicit stakes here are: is Kehinde Wiley as “good” as the old dead White Old Masters? More broadly, can people create art today that is as good as—or better than—what’s in the “canon”? While it’s impossible to know what will have long-term impact, I see no reason to elevate, say, Titian as intrinsically superior to Wiley. We can appreciate the old stuff while still making new stuff that’s vital and relevant to our current times. Provocatively, earier in the video, we see Wiley using a photographic reference.

Neil Cohn has provided lovely summaries about how a Western bias toward personal creativity and away from rote copying has prevented them from learning to draw, and I think this ties closely to Romantic notions of artistic genius.

Technology creates styles

Hockney makes another related claim that significantly complicates things. He points out that artists’ styles might have changed even when artists weren’t using optical aids. For example, perhaps some artists (such as Vermeer) used optical aids that gave their work a luminous, detailed look. Then, subsequent artists might have also adopted this look even if they weren’t using optical aids.

We’ve certainly seen this with photography, and later with computer graphics. In one presentation, when I showed this computer-generated rendering of a 3D model:

an art historian in the audience commented that this is viewpoint that you would never have seen in the entire history of classical painting. But now it seems so ordinary.

Whether you’re looking ancient Chinese scroll painting, Russian reverse perspective, or Renaissance Madonnas, generall all of the figures will be clearly framed and visible, seen from a few different viewpoints, with fairly balanced compositions. (I’m oversimplifying, obviously.) The Impressionsts were the first movement with visual styles influenced by the visual look of early photography; photographs could be suggestive even if they were blurry or low-quality, and, possibly, even more intriguing than all-in-focus imagery.

The invention of photography transformed the way people painted realistic pictures, in ways that are often very subtle. Many of my own paintings use crops and compositions that no classical painter would have used, but now seem commonplace in the age of ubiquitous photography.

Ernst Gombrich began his classic text Art and Illusion with the following question: why did different artists in different times in history use different styles? Why didn’t the ancient Egyptians or Renaissance Old Masters paint like Impressionists? The answer is that styles had to be invented. Styles don’t just exist. New technology is one of the tools that leads us to invent new styles.

Dichotomous thinking

In these debates, both Hockney and Stork get caught up in little details of whether, say, a particular sphere is too perfect or not perfect enough to be optical, which thus somehow conclusively proves or disproves his thesis. These examples are of limited usefulness in my opinion. I think there’s a limit to the value in judging just how “perfect” some perspective lines or spheres are. People might not have drawn perfect lines or curves for lots of reasons, whether or not they were using optical devices.

In other situations, Hockney keeps a more flexible position, which I think makes more sense, although it also makes most of his claims really unverifiable. The hypothesis here can’t be all-or-nothing; the most likely thing is that these tools were useful in some ways, had some influence, and were part of practice, but not that they were used at all times for all things.

Overfitting

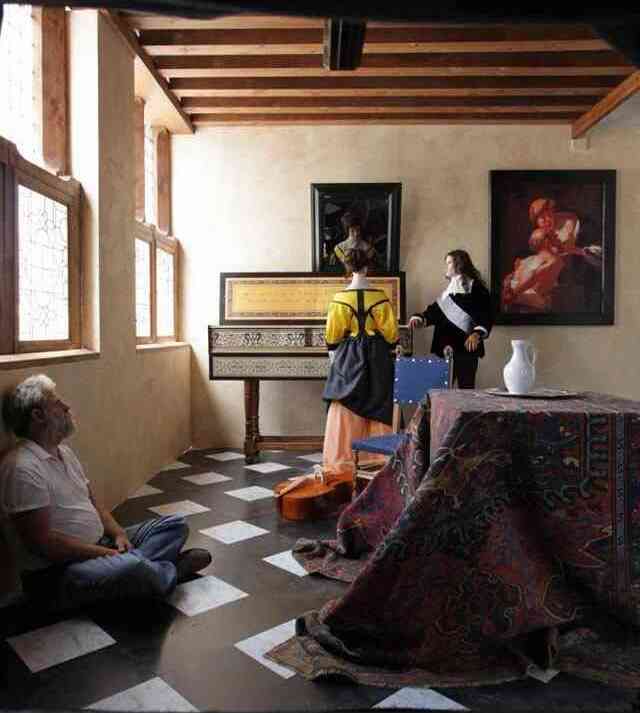

One minor point about Tim’s Vermeer: he recreated the music room to look just like the painting, since we don’t know what the actual music room looked like. There’s some danger of “overfitting” here.

Tim compares setting up the room to photography, which seems apt. He’s not simulating real natural light as it changes in the world, he’s constructing an environment that looks like a picture, akin to an Ames room. The colors and tones in the room match the picture, not whatever light Vermeer actually saw. Tim could have just as well put a Vermeer print on the wall and copied it that way.

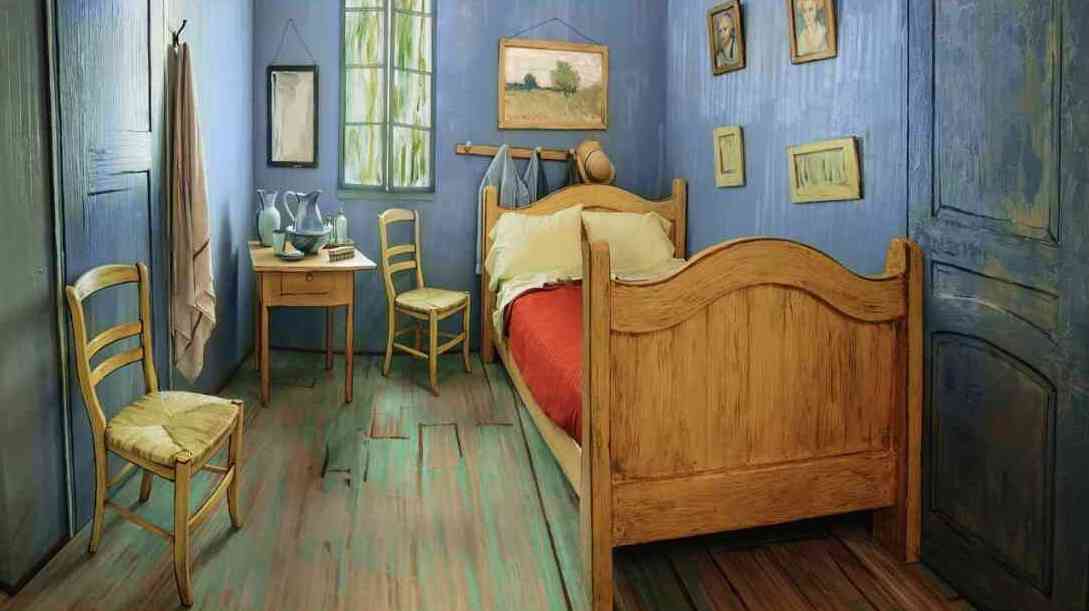

Still, his demonstration is still more persuasive than if, say, someone claimed that Van Gogh’s “Bedroom at Arles” is a photometrically-accurate depiction of what Van Gogh saw (and some have made related arguments).

A meditation on perspective

I conclude with this insightful clip from the brilliant “Cunk on Earth,” which made the Internet rounds recently:

Thanks to people who recommended Tim’s Vermeer: Daniel Ambrosi, Tzu-Mao Li, Robert Pepperell.