Status Quo Bias

The effects of new technologies can be complex and nuanced. In the words of Kranzberg’s First Law, “Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral”. As he describes, the consequences of new technologies can be subtle, complex, and hard-to-predict, and vary depending on the context in which they’re deployed. There are legitimate criticisms to be raised against any new technology, but instead we often hear simplistic, knee-jerk responses. This post discusses some of where they come from.

This post began as a section in a much longer post on how technology changes art, but I decided to separate it out here. It’s not meant to be a complete discussion, just a few tidbits.

There are numerous famous examples of people condemning new technologies that we now take for granted. Plato bemoaned that invention of writing would ruin ruin peoples’ memories.

We often cite such naive initial responses to previous technologies, with the implication that modern critics are making similar mistakes. This is not to say that a new technology is above criticism, but that simplistic takes like “it’s not art because you just pressed a button” are just as short-sighted for “AI” art as they were for photography.

In a 1999 essay, the novelist Douglas Adams wrote:

- Anything that is in the world when you're born is normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works.

- Anything that's invented between when you're fifteen and thirty-five is new and exciting and revolutionary and you can probably get a career in it.

- Anything invented after you’re thirty-five is against the natural order of things.

This is now called Status Quo bias, an emotional preference for the current state of things. In one recent study, researchers’ found evidence supporting Adams’ description. They described a new technology to participants, and, for each participant, told them a different year of the technology’s invention. They repeated this for many technologies and participants, and they found that peoples’ judgments of whether a new technology is beneficial is best predicted by whether it was invented before or after they were born.

Another set of studies show that people have continually perceived morality to be in decline over at least the last 70 years, and that this is a psychological illusion.

| New technology can indeed have significantly negative impacts, but the initial backlash often gets it completely wrong. The consequences of new technologies are subtle and complex. The trick is to accurately judge the harms (and benefits) from the very initial stages of a thing. |

The author Raymond Williams traced complaints of a lost rural country life of the author’s childhood back from the 1970s to the 12th Century.

Sociologists and psychologists have several theories why some people tend to catastrophize about new technologies. One possible explanation is that, it’s hard to imagine the unexplored benefits of new inventions—which are diffuse and ambiguous—as compared to the very real prospect of losing something valuable that we have now.

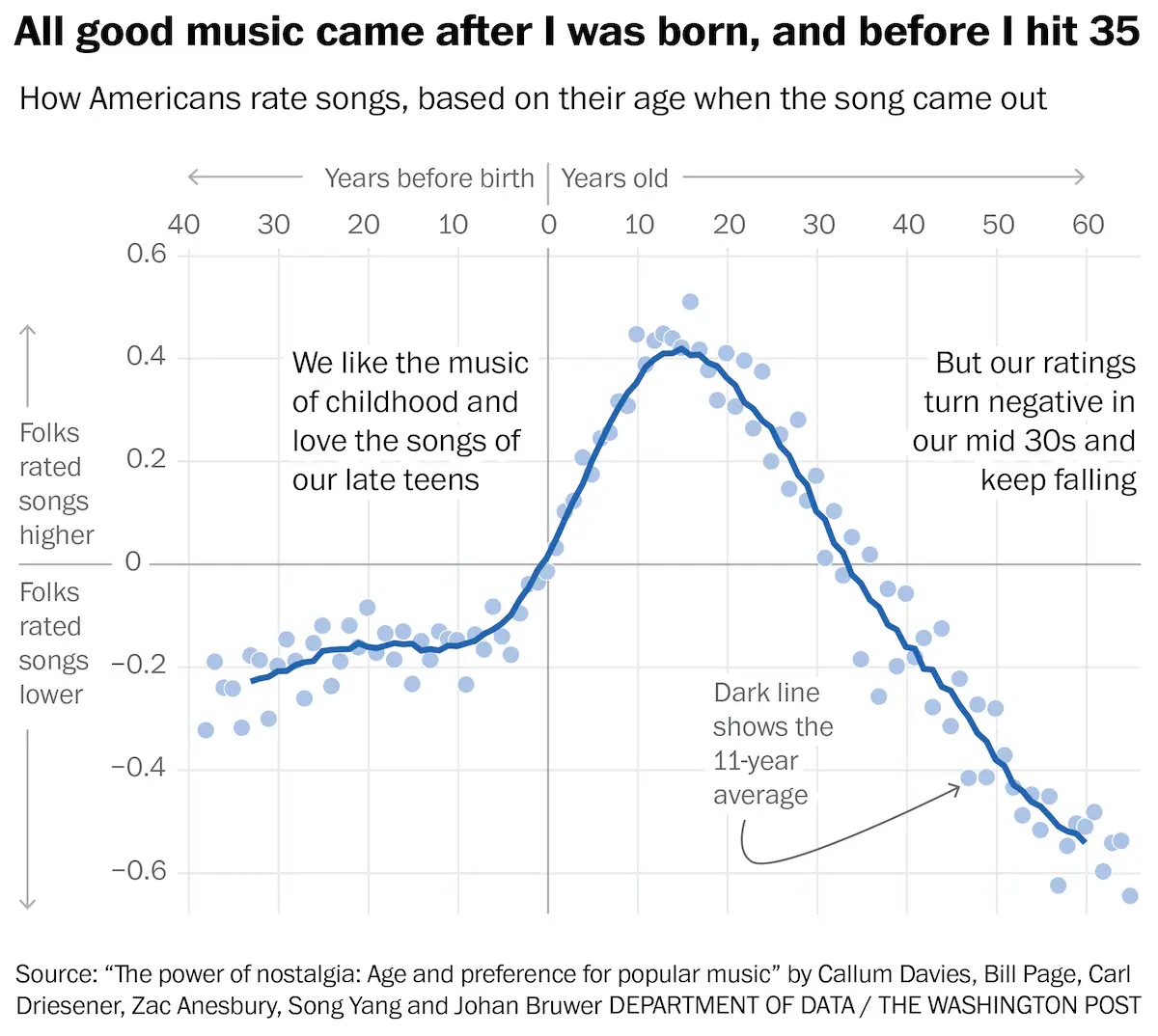

We prefer the music of our formative years

Something similar happens with artistic taste. So many times have I heard someone say “All of today’s music sucks, it was better in the 90s” or “the 80s” or in the days of The Beatles and Elvis. Somehow it has all gone downhill since the speaker came of age. Indeed, numerous studies show that people prefer the music from their youth. A more recent study reported by the Washington Post reached similar conclusions.

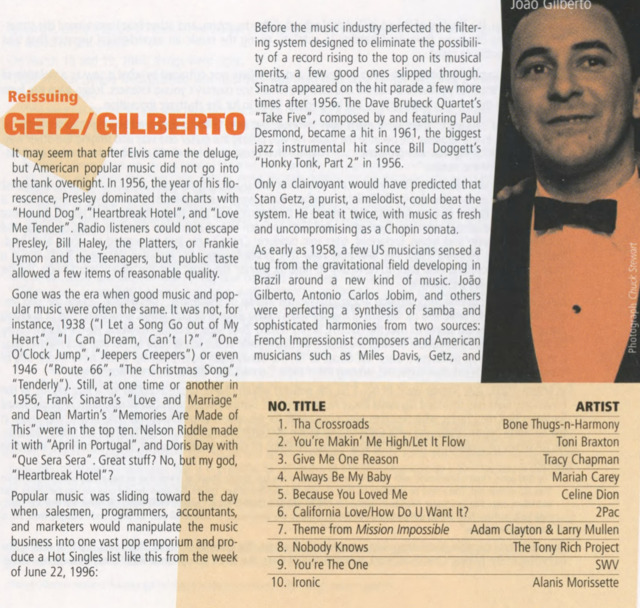

I found my favorite example years ago when I bought a CD reissue of “Getz/Gilberto,” which included these liner notes by a jazz critic:

For this critic, it was self-evident that pop music had become garbage by 1956, and was garbage ever since then.

More recently, here’s a video with a strong “they don’t make good music anymore” vibe:

While I’ve enjoyed a lot of his videos—and he clearly knows way more about music than I do—here he’s making a lot of snap decisions, out-of-context, comparing new songs according to some of his treasured, sentimental favorites of the 80s and earlier.

Notably, many of the comments agreeing with the video talk about childhood memories. The first comment that appears is “The problem is that everything sounds like an inferior copy of something better you’ve already heard.” Of course: if you’ve already formed your ideas of what good music is, then everything new can only be compared to what you’ve heard before, and it can never be as good.

But maybe this is a criticism of commercial, pushed-by-Spotify music, which might be a more legitimate concern.

In a subsequent video, he claims music is getting worse because music is too easy to make. Just like Michaelangelo, who painted in fresco, thought that oil paint was too easy.