Learning from Painting, Part 2: The Goal

This is the second part of a series of blog posts about my recent experience in digital painting and drawing. Click here for the first part. The images on this page were drawn between

When starting to draw or paint a picture, I had to have some goals. My high-level goals were easy: to learn things and enjoy myself. But an individual painting requires some kind of more concrete goal at the outset. What is this picture about? What am I trying to do here? I didn’t have anyone to give me goals. I had no teacher, no mentor, no job or school requirements to give me direction.

One of the most important things I realized was how better how to think about my goals in painting.

Aiming for realism

I started out solely painting from life, without photography, in order to better develop my skills.

Usually I aimed to make pictures look as realistic as possible. Here’s an example, from a side-trip from Oxford:

This doesn’t look very realistic. Does that make it a failure? Obviously not, because I was happy with it, and I got good comments from friends.

Here’s one out the window of a train, which forms an “impression,” which is a sort of subjective realism:

Of course, if you really want something as realistic as possible, there’s no need to paint; you might as well just take a picture.

Reference photos

At some point, I started to take photographs along with my drawings. For one thing, having a photo helped if in case I wanted to finish the painting later on.

And I noticed two things. First, putting the photograph next to the painting made the painting look “wrong.” Side-by-side, I could see all the technical flaws in the painting, all the ways I failed to capture reality.

Second, I didn’t care. I still liked the painting more.

I concluded I could solve this “problem” by not showing these photographs publicly.

I’ll make an exception to this rule, to show one example:

I like the paintings, but I think that seeing it next to the photo makes it worse.

In the words of Julia Child, “Whatever happens in the kitchen, never apologize.” Or, as Amanda remembers it: “Never tell your guests what your dish was supposed to be like.”

Eventually, I reached a point where I often think my paintings often think they look pretty good even next to the photograph. But I still don’t show the photographs. I’ll let my drawings be appreciated or not appreciated on their own, without this distraction.

The real goal

This seemed like a contradiction: I wanted to make images look as real as possible, yet, I didn’t want to duplicate photographs, and I was quite happy when my pictures were not photographic.

I thought back to a book I’d read the previous month, which (in my memory anyway) explained that Matisse and Picasso liberated painting from a focus on representation. Even though their paintings clearly represented real scenes and objects, their paintings are really about beauty, abstraction, design, and other visual qualities, not about reality. Reality provided them a starting-off point for art, not a goal.

In short, after Matisse and Picasso, a picture is a picture; how well it depicts the real world is often not important at all.

These thoughts led me to the following realization, which seems completely obvious, even vacuous, but is really quite important:

What is a “good” picture? Well, there are lots of ways that a picture can be “good.” For me, “good” does not mean photorealistic. It means that I like looking at it, that other people like looking at it. Depicting reality can be part of it. Or perhaps the picture conveys something about my subjective experience. Or maybe it just looks nice.

To some extent, this answers some of my confusion from college: why not draw that street sign? Because drawing that street sign served no purpose in that picture; it didn’t make it better.

As described previously, when I start a new picture, I don’t know what I’m going end up with. I start out with some goals, like capturing lighting, but the goals might change along the way. In advance, I don’t know what—if anything—my picture will be “good” at: will it be a nice composition? Will it convey the space? Will it fail at all of these things but achieve something different?

I always start out with some kind of a concrete goal. But, ultimately, I seek only a picture that somehow achieves something.

Using photography

Once I’d gotten more practice with drawing from life, I experimented with drawing directly from photographs. At first, these drawings looked dull and lifeless:

It was like the photograph had lost something of the real experience, something that hadn’t been replaced.

Then I found a way to use photographs. One day, I had an image on a train platform that I wanted to try drawing. But I didn’t have time to stop, so I took a picture, and then drew a picture later, guided by my memory, but using the photograph as reference:

This seemed promising, so I kept doing it.

For example, walking down a dark street, this scene struck my fancy. I had a sense of the “body language” of the streetcars, but I didn’t have time to stop to draw. So I took a photo and drew this later:

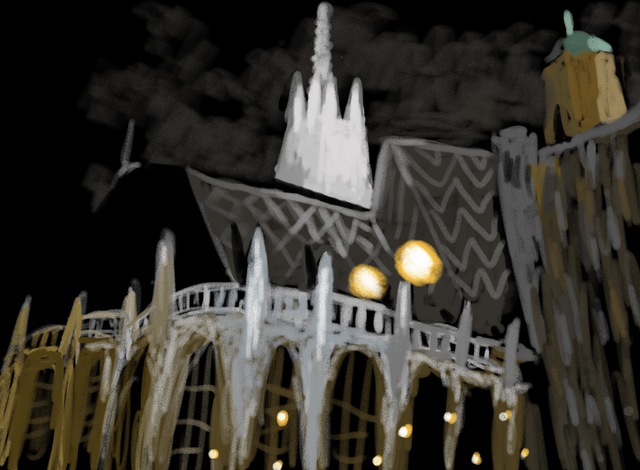

Here are a two more drawings from the same week after my sabbatical, also made using photographs as memory aid/references. The first explored the gesture of a church pointing upward in dramatic night lighting:

And, in the second, I was thinking of the hyperreal perfection of “photorealistic” painters like Richard Estes:

If I’d been able to stop at these spots and draw, the results would have looked different. Like the other choices mentioned in my previous post, choosing to draw from a photo is one more choice that leads to different styles, different outcomes, not better or worse than the alternatives.

The next post in this series is here.

The images on this page were drawn in August and September 2019.