Learning from Painting, Part 1: Art is a Process

In July 2019, I got a new iPad and Apple Pencil, and experimented with some drawing apps. In college, I had studied art (and computer science), but I stopped painting after I graduated. This digital drawing on the iPad was my first real attempt at painting in more than 20 years:

and I was hooked. In the following nine months, I spent much of my time drawing and painting on the iPad, and I learned so much.

This is the first of a series of blog posts about these experiences. Some of these observations are things I’d wish I’d known when I first studied painting and drawing in college, and some inform my further thinking about these topics.

While my own art education gave me valuable experience, it gave me almost no conceptual framework for creating art, appreciating art, or making a career of art. I graduated entirely confused about what art is about. So I’ve recently been more actively educating myself, including reading extensively and talking to artists. But there’s no replacement for trying to create art.

I really dove into painting digitally last Fall, when I was fortunate to have a one-month sabbatical, most of which I spent in Oxford, England. An academic sabbatical is a chance to step back from one’s normal research and duties, and explore new directions. For this sabbatical, I decided to dive more seriously into painting and drawing, sometimes spending hours a day painting digitally, letting go of the usual feeling that I “should be more productive.” I told myself that painting was “my job.” (I did do a bunch of other professional and personal activities in this time as well.)

I’m not making much art these days; this stay-at-home pandemic seems to have ended whatever momentum I had. So I suppose it’s finally time to write down the reflections that have been brewing in my head over the past year. Some of these ideas have already led to new research projects, and others are still forming. I’m also writing these things down because they’re the things I wish I’d known a long time ago.

Art Comes From A Process

One important lesson that I kept relearning over and over is that art comes from a process.

My paintings often disappointed me, since they were far from what I’d intended in the first place; they showed my poor skills and lack of control over the outcome. I did get better at guiding this process. But that first meant learning that I can’t predict how a drawing is going to turn out, and that this is ok. It’s about following the process, not about trying to produce a specific result.

On my third day in Oxford, I decided to try digital watercolor simulation. After a few minutes of painting, I had this:

which I found unsatisfying, I was trying to draw so much detail that was too difficult to capture. So I decided to try drawing black outlines around it, producing this:

which was not what I’d intended at all; but I was pleased with it.

A few days later, I visited a new cafe, and decided to try digital pastels out while looking at some flowers on the table. Partway through, I thought the drawing was too messy, and so I decided to add outlines again, ending up with this:

It surprised me how recognizable the style seemed, like I’ve seen hundreds or thousands of other drawings in this style that I wasn’t thinking about at all.

An important thing to remember in these early drawings is: I was trying to make a very realistic picture. If I could have produced something that looked close to a photograph, perhaps I would have. And the ways I fell short weren’t failures; they were the artistic style. Nonetheless, I kept working to improve my depiction skills.

But the main lesson here is that you don’t decide the outcome in advance; you explore, and come up with something that you didn’t couldn’t have foreseen at all. I always have to start with some idea or goal for the picture. But I also have to be ready to shift or abandon that initial idea as the picture emerges. Researchers will recognize that many research projects are like this too: you can’t accurately predict what will be in the final paper when you are first brainstorming the project.

In my readings, I’ve come across numerous quotes from artists who say some version of the same thing, but I wouldn’t have appreciated these quotes had I not had the same experience. For example, the artist Francis Bacon: “one has an intention, but what really happens comes about in working … You are following this cloud of sensation in yourself, but don’t know what it really is. And it’s called instinct.”

This quote so richly describes the key facts of this process. I’ll have a lot more to say about it in future posts.

Initial choices make big differences

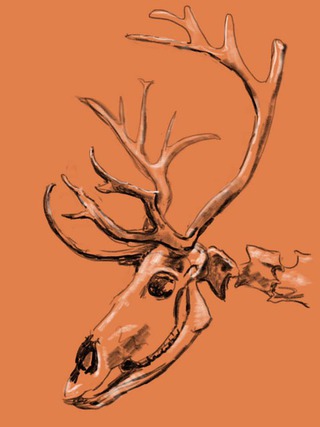

A few weeks later, after I’d had more practice, I went to the Natural History Museum to look for things to draw. I meant to select the oil paint brush, but forgot and accidentally started drawing with the pencil tool, which is the default in the app I use. I found that I liked it, and I ended up with these:

which are totally unlike what I would have drawn with the oil brush, and I probably would have been frustrated drawing this in oil anyway.

I found that picking the background color first completely changed the outcome. Originally I thought that I could draw the subject and pick the background later, but that doesn’t work. Here’s a California grizzly bear, at the same museum:

and here’s what happens if I later decided I wanted a different background color:

This isn’t the best example, but both the transparency and color/lighting don’t match any more.

Medium and background color are two choices that seem incidental, and yet completely change the outcome of the drawing. And the whole process is a sequence of these kinds of choices, each of which drives the painting toward a different final outcome. It’s like a Choose Your Own Adventure Novel or a chaos theory experiment where small decisions early in the process will lead to utterly different results in the end.

Making Art is An Emotional Roller Coaster

Here is the first painting I made in Oxford, at Keble College:

I was not happy with it; I’d tried to draw a very complicated and textured building and didn’t capture any of it. But I got nice comments on it on Facebook. And the second painting of the trip, from that same morning, got more positive comments.

I’ve always found art to be a highly neurotic process. My thought process, during any given drawing or painting, can be roughly summarized like “this doesn’t seem like it’s going to work…this seems hard…this isn’t working…this isn’t any good…hmm, maybe this isn’t so bad…this is coming together actually…maybe this is ok…is this ok?” When I’m done, I often go back and forth between being quite satisfied with what I’ve done and being disappointed by how amateurish it all is.

The thing that kept me going, especially early on when I was really struggling and unsure, was positive comments and encouragement from my friends in Oxford and on social media. And sometimes I was happy with how things went; here are a digital watercolor and a digital oil also from the first week in Oxford:

I think this neuroticism is normal in any creative activity. I know so many people who say “I’m bad at art” and give up even before they’ve begun. Unless you’re doing something very practiced and functional like certain kinds of professional illustration, making art is something new every time—at the very least, new to you—and it is normally full of uncertainty. Part of the practice of art is to learn to recognize, acknowledge, and set aside the anxiety of uncertainty. Embrace the uncertainty, and embrace the potential for “failure.” I made a lot of drawings that I think suck, and I’m ok with that. No one else has to see them, after all. As Ed Catmull says, “it’s only a failure if you don’t learn from it.”

The next post in this series is here

The images on this page were drawn in July and August 2019.