Painting in Karies

I originally wrote this post in 2005, as I started to reflect more on my experience as an art student, how little I understood about art as a student, and how it relates to my research now.

In the Summer of 1994, I took a three-week intensive course in painting in Karies, a small village in Greece. One of my instructors in college, Bas Poulos, created and ran the program. Bas grew up in South Carolina, but his parents had emigrated there from Karies long ago, and he returned to his ancestral home every summer, and, more recently, begun this painting program. There were two other students in the program that Summer, Erik and Elaine.

We painted in watercolor for six hours a day: three in the morning, and three in the afternoon, including critiques. Bas told us many stories about the village, introduced us to Greek food and customs, and showed us around the vicinity, including Sparta and Monemvassia.

I finally got around to putting this stuff up on the web because of something I see often in non-photorealistic rendering research papers: typically, you will read something to the effect that “artists show important details while abstracting out unimportant details.” (Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics is often cited.) I’ve always been puzzled by this statement—it makes sense superficially, but what does it really mean? What makes one detail important and another unimportant? How do you define what a detail is? And how do you remove an unimportant detail without changing the meanings of the objects around it?

Thinking back to Karies, I realized that this is not the first time I was puzzled by this question.

Here are some paintings from that summer (which should make it clear why I didn’t become a professional artist), along with my memories from the program. I don’t remember the precise chronology, so, when in doubt, I’ve arranged them to tell a better story.

1.

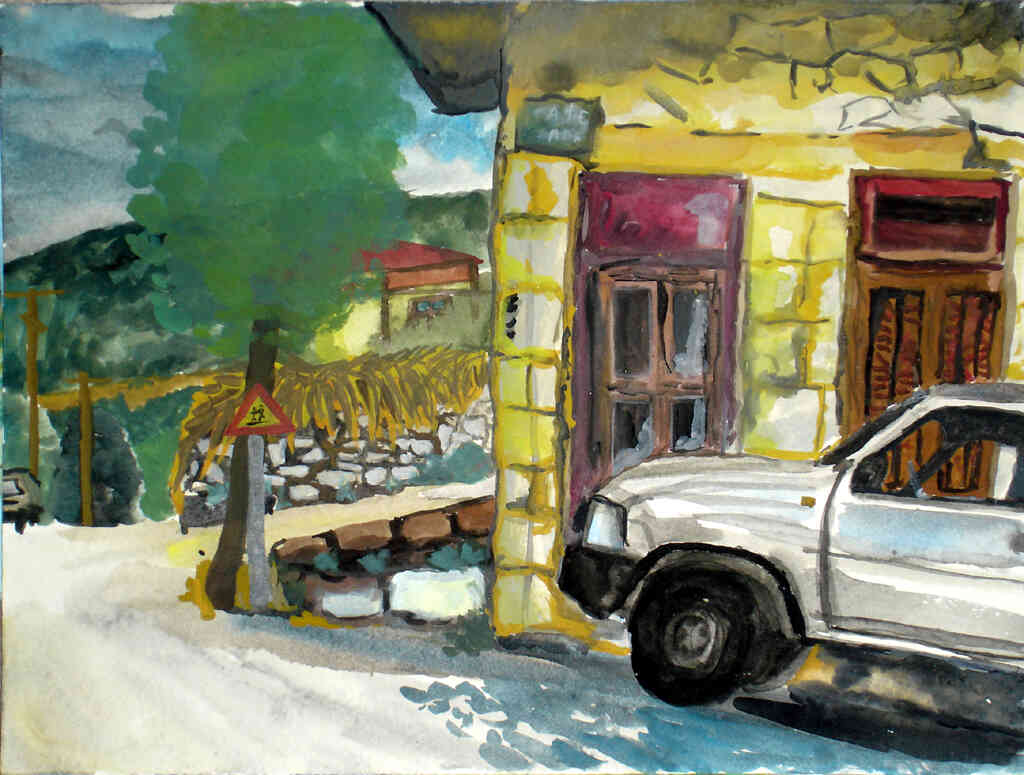

After warming up by painting some postcards (which I don’t have any more, since I mailed them), we went out for our first big painting; here’s mine:

In the critique session, Bas criticized my literalmindedness. Why did I draw that street sign? I said I drew it because it was there, and he said why do you have to draw it just because it was there? In retrospect, I wanted to capture the experience of the scene I was looking at, and to me that meant capturing the visual complexity by painting in all the details.

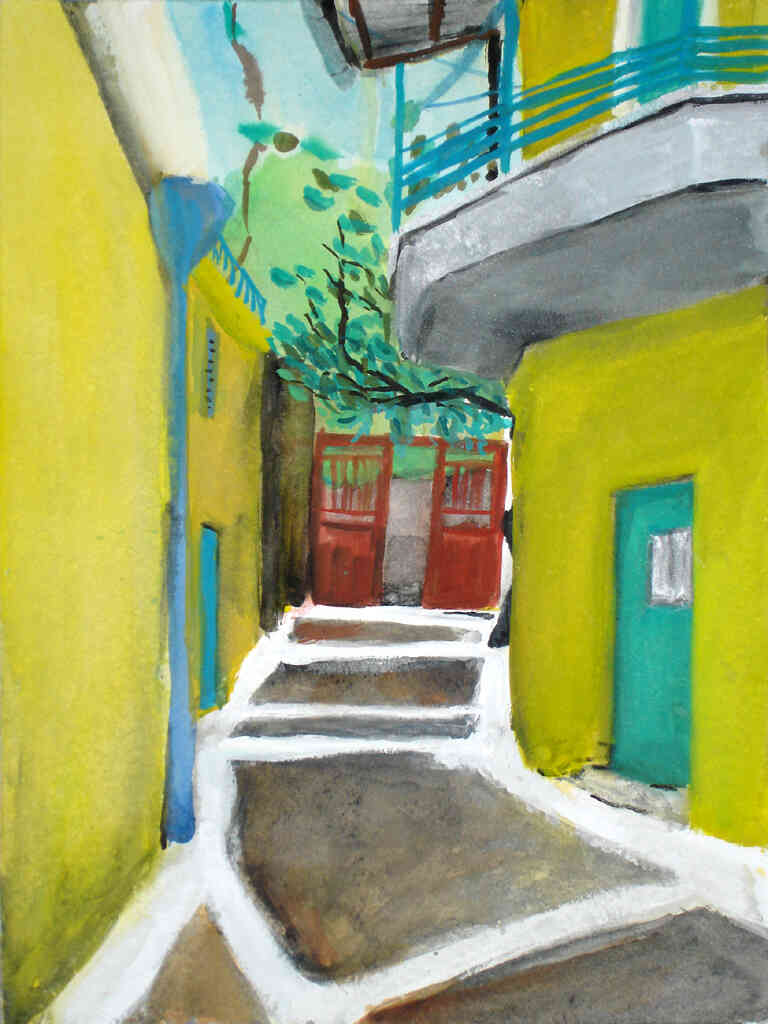

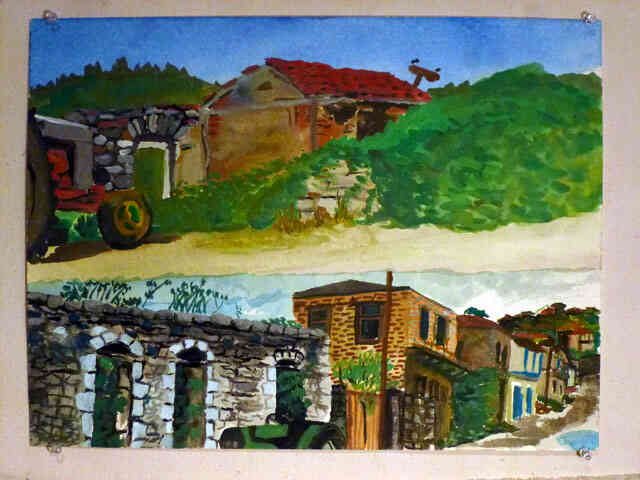

In the next few paintings, I had some fun with the twisty 3D spaces in the village’s mountain streets:

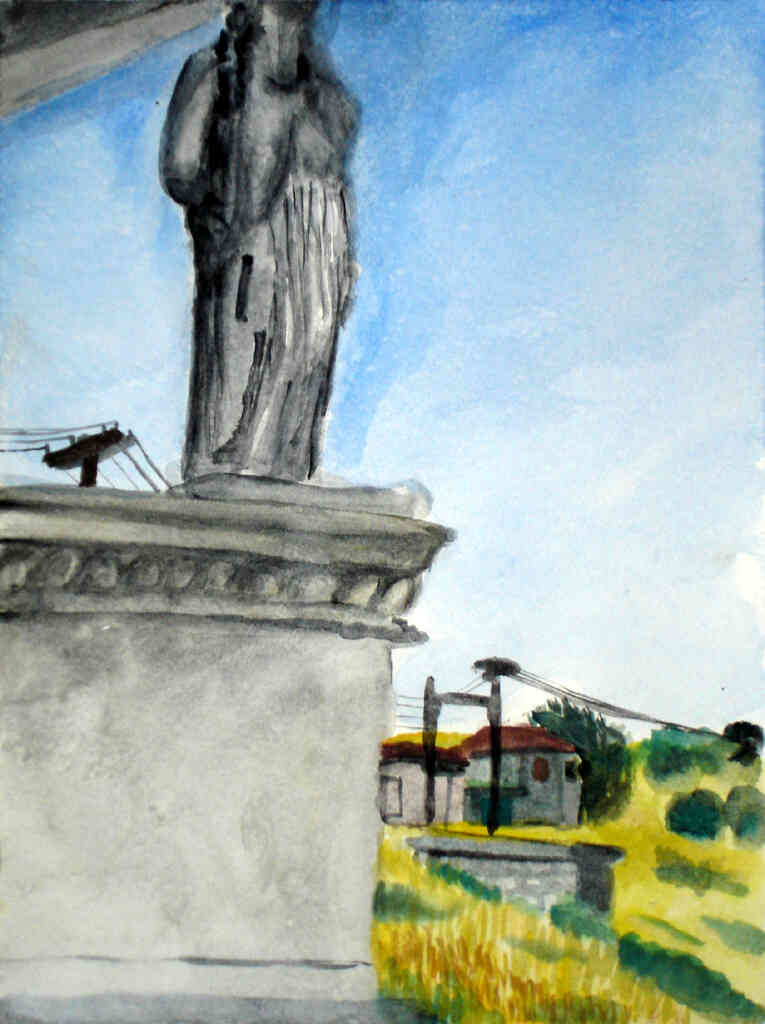

We continued with different subjects in different locations, such as the town square, and in a nearby village called Monemvassia, where I struggled with the rocky hills in vain:

Karies is supposedly the home of caryatids, although it is not the only location to claim that distinction.

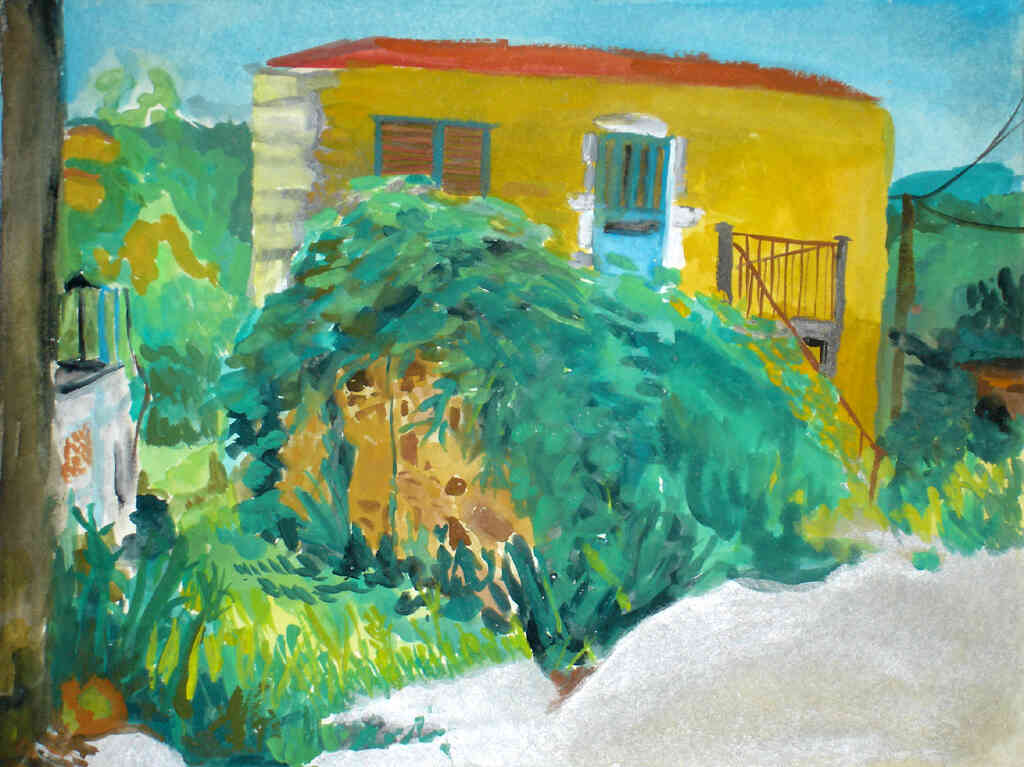

The main thing I remember about this one was the gigantic, colorful insects that were crawling all around me while I painted it:

In all of the images up to here, you can see a literalminded focus on the overal shape and appearance of the scene, but details such as streetsigns are already starting to go missing. You can also see failed attempts to paint every detail in very complex scenes (there are more examples of this in the paintings that I didn’t put online) — there’s just not enough time in 2.5 hours to work in such detail, and it always came at the expense of the overall composition.

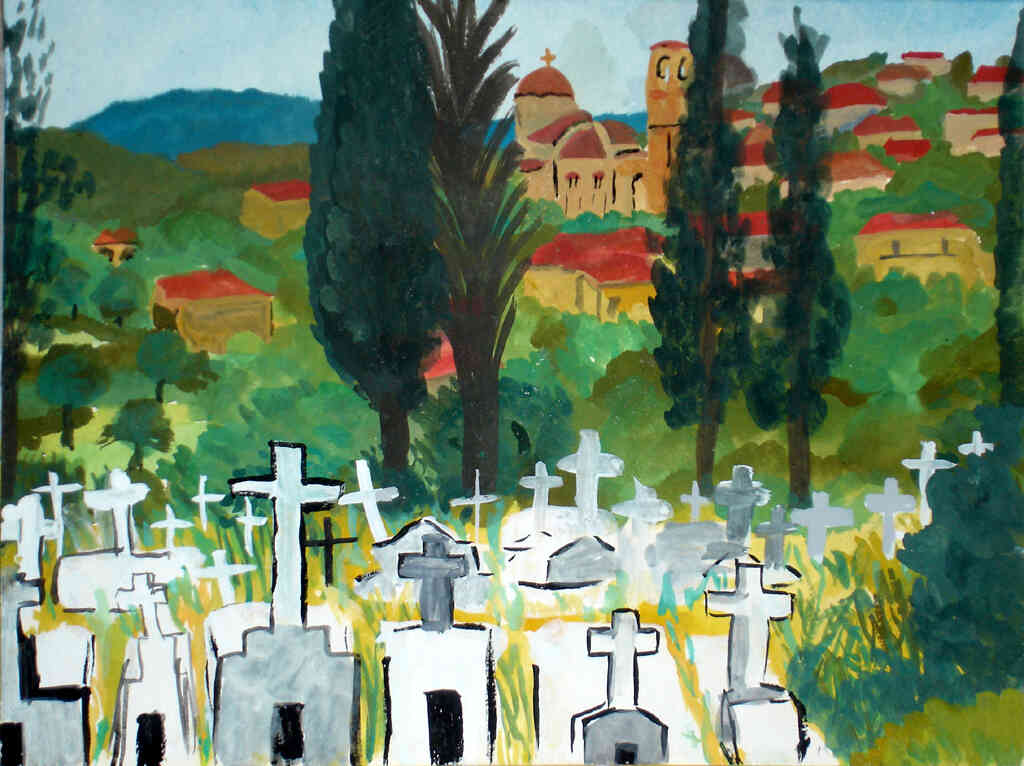

My best painting from the program was a sort of improvised diptych that, for some reason, worked out really well. One condition of the program was that Bas would select and keep one of our paintings for his own collection to show in the future—this is the painting he chose:</p>

2.

At some point, I started to get frustrated, and painted stuff like this:

I felt uninspired and hated the picture. And, in the critique that day, Bas came in and told us that all our paintings were terrible. I agreed with him about all three. But I wasn’t sure how to get out of the rut, or find the next step. At some point I also painted this:

I was experimenting, trying to find something interesting to create, but it wasn’t working. He said: “You can’t do that until you’ve developed your own mark-making style.” I didn’t know what that meant, and I’m still trying to figure it out.

My mood wasn’t helped by getting sick—twice, in succession. As I recall, it was a combination of food poisoning (from some bad feta cheese, apparently) followed by a cold, and possibly too much time in the hot sun.

3.

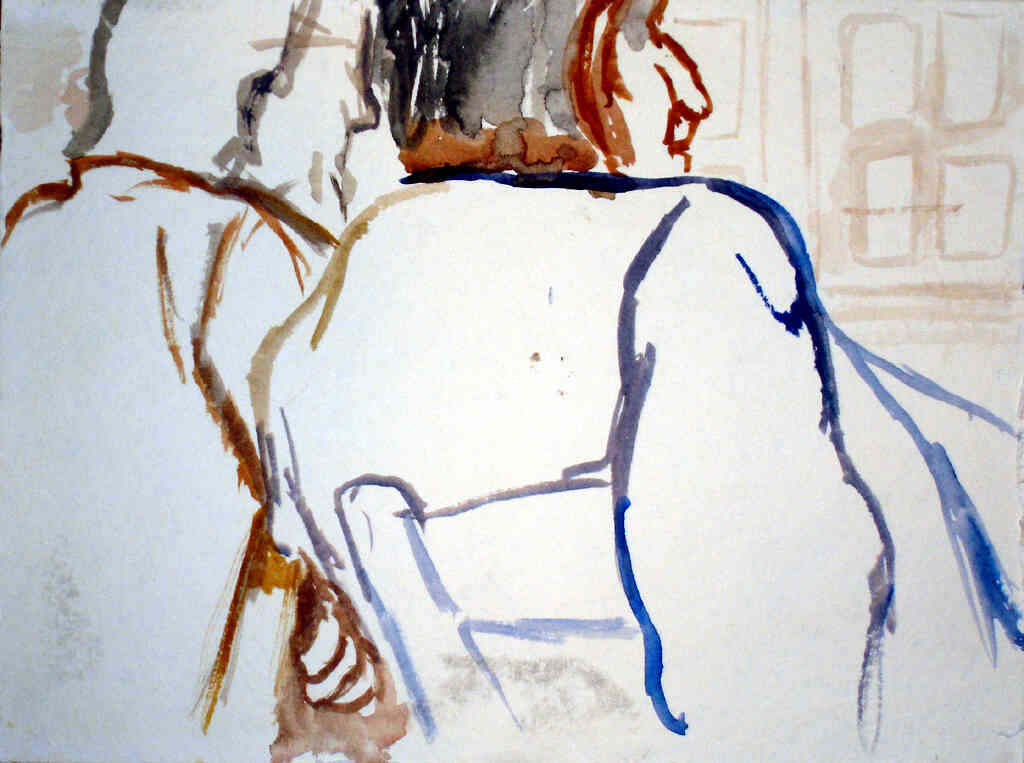

Sometime during the program, there was an election for some sort of European representatives, and Europeans were required to vote in their places of birth. So, one day, the village square was filled with outsiders, children of the village who had moved on to bigger and better things, but come home on this day to vote. We took our watercolors and our paper blocks out to the square and made some quick, surreptitious sketches:

This was immensely satisfying. However, my best painting from this day isn’t shown here. It was a portrait, and Bas liked it enough to show it during an exhibition of our work towards the end of the program. The exhibition was held in one of the village tavernas. Apparently, my portait’s subject became incensed at seeing his painting on the wall and tore it down and ripped it up. Bas told me later that this guy was sort of the local “village idiot.” He told me that this incident would add me to the local lore of the village.

I asked Bas what the villagers say when they look at the paintings in the exhibition. He said that most of the conversation is along the lines of “Why didn’t he paint my house instead of this one? My house is much nicer.”

4.

For the most part, I was pretty frustrated.

Looking back, it seems like the paintings from the end of the program

are starting to show some of that abstraction that Bas talked about at

the beginning.

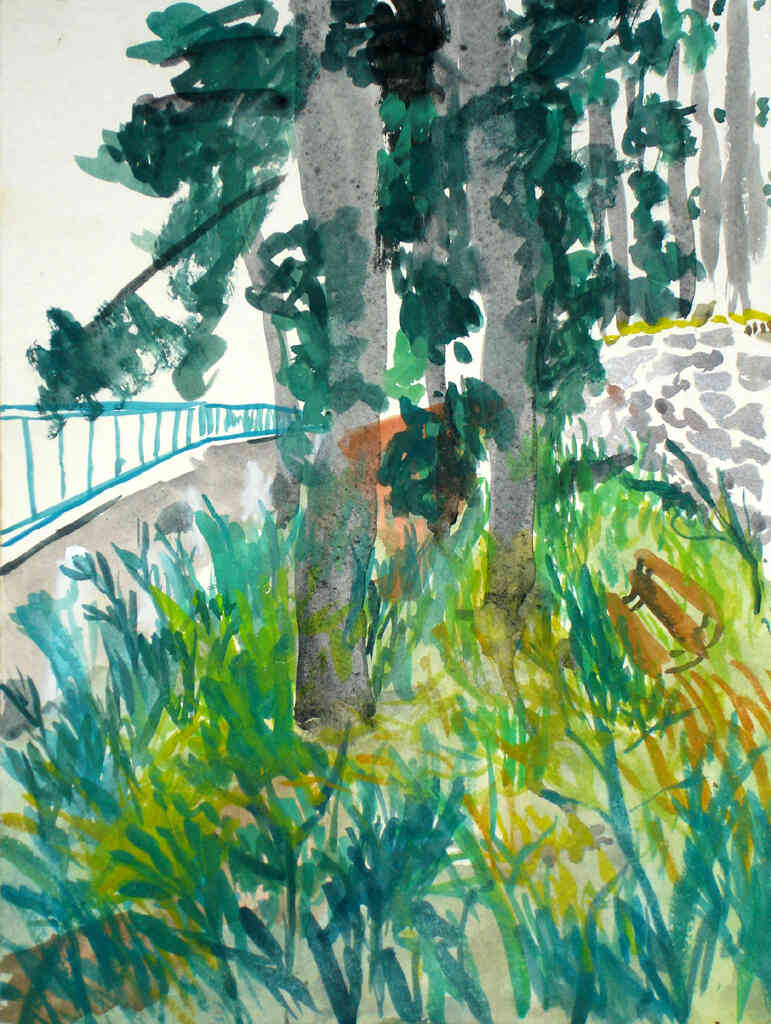

I remember painting this on a gray day as it started to rain:

It’s now one of my favorites from the program. It’s abstract but expressive, economical, with a nice contrast between the yellow and the gray, as well as a perfect expression of my mood at the time. I don’t remember when this one was painted, but it also fits in here at the end:

Not perfect, but I like the economy of it. And the very last painting before we said our goodbyes and moved on:

It’s not a beautiful painting, but I think it has a good sense of composition, of expression, and it omits many unimportant details while retaining important ones.

More than two decades later, _I picked up painting again, this time, digitally.

Here are a few other paintings from college: