Amateurs: Making Art at Technological Cutting-Edges

Reading Michael Naimark’s splendid essay on First Word Art / Last Word Art recently had me reflecting on all the “First Word” artists I’ve been lucky to meet personally. As he puts it, First word artists are experimenters that create new forms, and Last word artists perfect them.

Artists that experiment at the boundary of new art and technology often share some personality traits: a restless experimental curiosity, an excitement for new possibilities, joy in the process, and a general disregard for disciplinary boundaries—especially the supposed boundary between art and science. Nowadays much of the community around artistic technologies occurs online, which also inspired this reminiscence.

Our popular narratives fail us by dividing artists and scientists into distinct, separate categories that never meet. A lot of artistic, technological, and scientific innovation happens at the intersection of these fields.

When artists develop and explore new art technologies—the films of the Lumières, the first hip-hop DJs—they’re dismissed or ignored by traditionalists. Then, within a few decades, some of these techniques become the new tradition.

No tools but the tools you build

Quite often, building the new art and the new tools go hand in hand. Sometimes it’s one person doing both, because the fastest way to get the tool you need is to invent it yourself. In other cases, artists and technologists work closely together.

Perhaps the most important technical innovation in the history of painting came from Jan van Eyck, who is famous for painting, not for inventing practical oil painting techniques. Likewise, the electric guitar is primarily attributed to Les Paul, a musician.

By nature, the user interfaces for new technologies, in a word, suck. You can’t perfect the tools when you’re still trying to figure out what you’re doing. There’s a certain kind of artist who doesn’t build their own tools but loves to work with the latest thing. During a brief time I spent at Stanford, I recall Lorie Loeb urging us to share our unfinished interfaces and not to wait for them to be perfect; she would work with whatever.

The light cycles in 1982’s “Tron” were animated by writing numbers on graph paper and handing them over to computer technicians. There was no GUI and no immediate feedback, since real-time graphics didn’t exist. The animators had never used computers before, and the computer technicians had never animated:

At a stylization demo at Pixar around 2009, I recall art director Ralph Eggleston telling us “I want to push the sliders past the ends. Engineers give us these interfaces and try to keep the sliders within safe ranges, but I find the most interesting stuff happens when you push them way too far.”

Restless experimentation and drive

We often think of the tools of the past as having been invented in a linear march of progress, which obscures the messy and fervent explosion of ideas that actually happened. People today compare recent developments in image synthesis to a Cambrian explosion, an apt metaphor for these periods of experimentation.

This really became clear to me when my father and I visited the Institut Lumière, home of the inventors of cinema (though Alvy Ray Smith later keenly informed me that they weren’t technically the first). Back when we visited in 2004, it was a time of active exploration in computational photography with all sorts of experimental capture and expressive imaging technologies, like panoramic stitching and light field cameras. But for me, analog photography had only ever been around as normal film cameras. So I was surprised to see some of the same kinds of experimentation happened more than 100 years ago: panoramic cameras, weird lenses, experimental color processes. More experiments and prototypes failed than succeeded. But from among the failures, successes emerged. In the words of Ed Catmull, “the only failure is if you don’t learn from it.”

Ken Perlin used to cite a Borgés story about a nation that punished artists for making art, so that only the truly driven—those who had to create—would make art, and thus they only had good art. While there are many flaws in the premise, it’s a vivid parable: the artist so driven to work that they willingly undergo torture, and produce masterpieces. In a way, one might say that producing experimental art is torturous, with software that repeatedly crashes, hardware that often fails. It takes a certain level of passion to put in so much time and hard work on an experiment. (I’ve never found the actual Borgés story, which I find nicely Borgésian.)

Occasionally I’ve shown some of my favorite experimental short animations to my students and colleagues, and we marvel at the staggering amount of effort involved. Consider “The Old Man and The Sea”, comprised entirely of oil paintings made by Alexander Petrov and his son. It’s literally hundreds of hours of work for every few seconds of animation. My friends would point out how utterly mad it seemed, and then I would point out how they spent day after day hunched over their computer terminals, writing code and spending hours debugging just to find a 0 that should have been a 1.

Amateurs

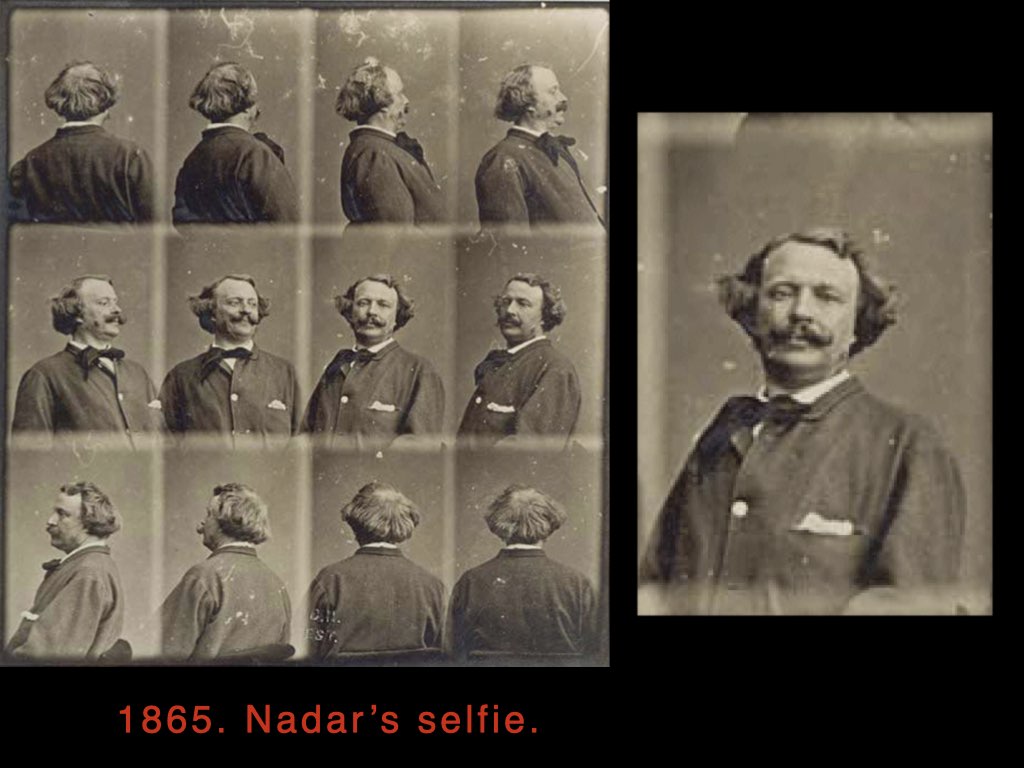

In 2016 I attended a talk where Michael Hawley described how amateurs invented photography, tinkerers who played around with chemicals and made pictures. He pointed out that, while “amateur” has a negative connotation today, it comes from the Latin root to love, and refers to someone who is passionate. Wikipedia says, “Historically, the amateur was considered to be the ideal balance between pure intent, open mind, and the interest or passion for a subject.” Hawley told wonderful stories about colorful characters like the flamboyant, balloon-piloting Nadar, while showing many of his wonderful early photographs.

Michael contrasted TV with television and cinema, which were designed by professional engineers, and digital media, which was “developed by both industrialists and hackers alike, launching our dazzling new generation of expressionists.”

In a way, anyone making art in a new medium is an amateur, because no one has ever used the new tools before.

It’s a setting where “Beginner’s Mind” is not just helpful but necessary. Michael himself won first prize in an international amateur piano competition. He was also kind enough to send me his slides when I asked, from them I drew several photos for use in my own talks.

No boundary between science and art

These kinds of innovators often don’t pay much attention to whether something is science or art or both. Walter Isaacson describes asking a curator whether Leonardo da Vinci would have considered his “deluge drawings” to be science or art. “I do not think Leonardo would have made that distinction,” the curator responds. He omits a key fact: neither the concepts of “science” nor of “art” existed during the Renaissance.

In my college education, art and science existed in separate faculties. I made some art with computers, and neither my art professors or computer science professors seemed to know what to make of it. Then, after graduation, I attended SIGGRAPH for the first time, and discovered a thriving community of people combining art and technology in many different ways; it changed my life.

(Perhaps the many childhood trips to The Exploratorium with my father had some influence on me as well, given the museum’s blend of science, art, and creativity. Certainly the Exploratorium experimental animation screening that he took me to when I was way too young had a big impact on me, and I still recall vividly many of those shorts, like ones from Oskar Fischinger, Norman McLaren, Parker and Alexeieff, and Peter Foldés. Supposedly Disney hooked a generation of kids on Disney animation by killing Bambi’s mother, and sometimes I wonder if that screening had the same effect on me.)

Walt Disney and Pixar each made enormous technological innovations in service of their art. Their decisionmaking didn’t prioritize technological goals but artistic goals. For example, the pre-Pixar teams’ race to solve “jaggies” led to importance sampling, a tasteful choice of aesthetics and algorithms, in contrast to labs that pursued other, worse, tradeoffs.

My thesis co-advisor Ken Perlin is a computer scientist who always seemed oblivious to disciplinary boundaries. He invented his noise algorithm to solve an artistic problem (expressive shaders) that he’d observed while working on Tron. In the lab, he would happily code away on his little Java applets, and often say with a gleam in his eye: “I’m making art, but I’m just not telling anybody it’s art.” The Whitney Art Museum later exhibited some of his applets online. Ken’s lab sat artists and computer scientists together, and we were next door to NYU ITP, where artists explored new technology, like Daniel Rozin’s delightful Wooden Mirror and Camille Utterback’s Text Rain video wall. (We also turned one of my papers into an interactive video installation.)

Many of these people present as humble and playful, just eager to show you their latest prototype. During one job interview, a congenial Midwestern interviewer named Gary happily showed me the latest thing he was tinkering with; only later I found out that this fellow had invented the laser printer in the 1960s. (This isn’t a rule though and all of us are complicated; Steve Jobs is perhaps the canonical example of someone who brilliantly fused technology and design but was also often an awful person.)

The sociology of art/science innovation

Someone should write a sociology/history of art at these cutting-edge spaces. Not just the events and discoveries, but the skills, personalities, and environments that make them possible.

Many of these experiments are lost to history; I remember being utterly stunned by a 2009 presentation of a seemingly-endless stream of cool artistic inventions by Disney Imagineer Lanny Smoot. I thought: who is this amazingly creative guy, and why had I never heard of any of his inventions? As far as I know, they remain largely hidden under the veil of corporate secrecy.

A lot has been written about the kinds of places that foster innovation and creativity (like Bell Labs), less about the places that aim to foster these art-technology connections (like the MIT Media Lab and Interval Research), and what makes these connections successful.

And so many delightful little experiments are little-known since they don’t feed into any larger narrative, like the Wooden Mirror, or Naimark’s Displacements which always sounded amazing. Many experiments are “ahead of their time,” not remembered like more mature works. Melies’ A Trip To The Moon is an astounding work of cinematic magic but today it takes some patience to watch.

History only exists when someone writes it, and we need people to do more of the work of organizing this history. There’s just too much innovation and too many cultures and communities to capture them all; the best, most-compellingly written history will become the best-known.

By the way, I highly recommend the book The Age of Wonder, a rip-roaring yarn about the adventurers who advanced art and science in the 19th century, and even invented the idea of science.

More people should know that you don’t have to keep art and science separate, and that it’s fun to play with them together.