Four Important Eras that Define Art

This blog post describes four Western art-historical eras, and why I think they are crucial to understanding how we talk about art today (at least in the US and Europe).

Today, we often talk about art in terms of ideas like intention, inspiration, expression, ideas, beauty, and craft. This is actually a mish-mash of ideas from different historical eras.

I suggest thinking of art history in terms of these Eras:

- The Artisan Era: prehistory to the 18th century

- The Romantic Era: the 18th-20th centuries

- The Modern Era: 1900s-1970s

- The Contemporary Era: 1970s-present

These eras correspond to four “modes” of art, each with their own conceptions of: the function and value of art, what an artist is and does, and the role of art in society and culture, and how artists get paid. In a sense, each mode corresponds to a different “definition of art.” Fully understanding a historical work involves understanding in which of these contexts it was created.

The years refer to when these modes came about, but art today might be made in any of these modes. The “Contemporary” mode mainly applies to what happens in a subset of the fine art world. We might more generally refer to our current era with the worn-out term “post-Modern.”

This division is an egregious oversimplification of history, and some of my scholarly friends might find it unforgiveable. But I find it useful for several reasons. It helps us better appreciate art from previous eras. But, even more, it helps us see how our current approaches to art are really current, and not universal. And, it clarifies where many of our conflicting definitions of art come from.

This description of the first two Eras summarizes The Invention of Art by Larry Shiner, revised from my previous post about it. I recommend this book if you’re looking for less of this egregious oversimplification.

I. The Artisan Era

Roughly, from prehistory to the 18th century

In 1479, the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception began hiring artisans to decorate the vault of their chapel in a church in Milan. They hired a woodcarver to craft a large altarpiece for spaces with paintings with carvings and decorations. They hired three painters to paint panels for the altarpiece. The contract for one of the panels, assigned to Leonardo da Vinci, specified that it should contain the Virgin Mary and child. The contract specified the angels on the side, the hills in the background, and even her clothing, “upper garments of ultramarine blue, brocaded in Gold.”

Leonardo was one of many artist/artisans hired to produce work to deck out a chapel in a church that would a provide a place for religious worship, while allowing the chapel’s patrons to demonstrate their wealth and status.

Today, we often think of artists as independent geniuses following their inspiration, elevated above mere craftworkers, with Leonardo as one of the greatest artists in history. Yet, Leonardo’s contractual fee was far less than that the fee paid to the woodcarver who made the altar. And it wasn’t just that Leonardo wasn’t yet considered a great artist—it was that the concept of “artist” did not even exist.

The “Art vs. Craft” division is recent

From antiquity to the late Renaissance, there was no distinction between “art” and “craft,” or even separate words to describe the two. There was no specific word for “artist.”Instead, words for “artisan” encapsulated everyone from playwrights to sculptors to painters to woodworkers to leathermakers. What we now call “the arts” were broadly in the same category as shipbuilding: they could be decorative, but they were always commissioned to serve a purpose. Sculpture and frescoes were commissioned for homes and temples; Greek plays served roles in temple rituals and festivals. “Art” had no existence outside of these functional roles.

The Greeks and the Romans did not have a separate word for “art” in the modern sense. They used the terms techne or ars, respectively, which included all the arts and crafts, and, more generally, described the process of making things. Plato and Aristotle carefully subdivided concepts but never distinguished “art” from “craft.”

Suppose you were a Renaissance architect, hired to build a new church for a diocese or parish. Above all, a building must be functional: it should serve its users’ needs. But the design also has other goals: to make visitors reflect with awe, and to appreciate the power and wealth of the church and its patrons, and your own skill. To complete the project, you must hire woodworkers, stonemasons, carver, painters, goldsmiths, and so on, to create this building that will serve various church functions. Among all of these artisans contributing to the building and its functions are the painters, people like Raphael and van Eyck, who (with their studios) made paintings for altars and chapels. And the commission might be quite specific about the content, like Leonardo’s contract for the Virgin and child.

Nowadays, we often look at Renaissance works isolated in museums or on websites, with their original contexts removed:

in a way that hides the purposes or original uses of the works. John Berger discussed this at length.

The arts in the Renaissance was dominated by the patronage system. What we now call art was always made for a specific place, serving a function in an altar or wealthy patron’s house. Artist/artistans worked on commissions from one of a few wealthy patrons. Artists had relatlively lowly status in the patronage system, but the Romantics worked to change that.

II. The Romantic Era

Roughly, from the 18th century to the 20th century

In 1683, the collection of Elias Ashmole was opened to the public in Oxford, creating the first public museum in the world. This invention signified epochal changes in the role of art and artists—and the ongoing separation of “art” from “craft.” New kinds of public art spaces emerged in the following century—including painting exhibitions, concerts, literary criticism, and even libraries—focusing, for the first time, on art itself. The first public museum in France, the Louvre, opened nearly a century later, initially to solve the problem of where to store the French revolution’s loot from the royalty.

In the 17th and 18th century, the power of the church and the aristocracy diminished, leading to fewer opportunities for artists in the patronage system. Instead, the middle class grew, forming a wealthy secular society apart from religious institutions. Here was a new audience for art in public spaces like museums and concerts, with the money to buy artworks. Marketplaces for art emerged. As a result, artists needed to promote themselves publicly. And, thery didn’t just promote themselves, they also began to argue for the importance of art itself, for the value of art for its own sake.

The Romantics advocated for revering art itself—and thus artists—as inspired genius. They appropriated religious concepts: Bizet said, “Beethoven is not a human, he is a God.” Artists must follow their imagination freely; Mussorsky put it “The Artist is a law unto himself.” The concept of the aesthetic, coined in the early 18th century, rose to describe artworks as having intrinsic, independent merits, requiring cultivation and quiet, reverent contemplation. Later slogans like “art for arts sake” advocated for the value of art separate from any purpose, while also elevating the status and value of artists.

From this period, we get the idea of an artist as an independent genius, driven by inspiration and imagination to create objects of reverent aesthetic appreciation, apart from any functional use. The artist, their inspiration, and their works are treated in near-religious terms. Art emphasized humanistic traits like emotion, reflection, and nature, as a counterpoint to the increasing dehumanization of the industrial revolution.

The separation of “arts” and “crafts” was gendered: the highly-valued “genius” associated with painting, theatre and music was the domain of men, and women were limited to the lowly “crafts” like sewing and knitting. Traditional artisanal roles sunk further in status with the rise of industrialization, as many artisans were reduced to being machine operators. Nonetheless a new kind of role, the designer, who worked within the industrial system but was not yet viewed as themselves an artist.

Other cultures often respond to these divisions after contact with the West. In 19th-century Japan, spurred by contact and trade with the West, the Meiji state consciously constructed the concept of bijutsu for fine art, and kogei for lowly crafts.

III. The Modern Era

Roughly, from the invention of photography to the 1970s

In the late 19th-century, the invention of photography forced artists to rethink the nature of art. This set in motion a half-century of manifestoes, movements, and revisions to the concept of “art” that we now lump together in Modern Art. Art didn’t need realistic colors or perspective (post-Impressionism, Fauvism), it didn’t need coherent shapes (cubism), it didn’t have to make sense (Dada), it could depict imaginary scenes (surrealism), it didn’t have to depict anything (abstract art), it didn’t require skill (conceptual art), it didn’t need to be movable (site-specific art), or even need a physical artifact at all (performance art). And also, photography could be art, depending on the expressive and aesthetic skills of the photographer.

Within a century, we were calling things “art” that would have been utterly foreign as art to previous generations. These things were also often baffling to the general public used to conventional notions of beauty and skill.

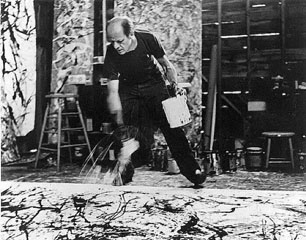

Artists became thought of not just as independent creators, but mavericks, outcasts, weirdos; like Salvador Dalí with his cultivated eccentricity. Artists adopted the mission of actively challenging norms and pushing boundaries. They achieved special status as innovators and creators. It was often considered a manly business; think of Picasso’s revolutionary painting of a group of nude prostitutes, and the image of Jackson Pollock flinging macho streaks of paint, while hard-drinking and carrying on an affair outside the studio.

“Modern Art” doesn’t mean all 20th-century art. “Modernism” and Modern Art was a specific movement. Modern Art is now a historical term for a movement, just like “Renaissance art” or “Rococo.”

Artists resisted the idea of rationality and industrialization that had led to two disastrous World Wars and mass dehumanization. Yet, art became an Enlightenment-esque project toward perfect art. The art critic Clement Greenberg pushed for the “purity” of visual abstraction as the apex of art, advocating artists like Jackson Pollock and Frank Stella.

Conceptual Art represented a more convincing endpoint for art, since it posited that anything could be art, depending on context. Critic Arthur Danto later wrote that Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes in 1964 indicated “the end of art”—the last step in a progression of movements developing the notion of what art is. But, more accurately, he was describing the end of Modernism.

IV. The Contemporary Era

(from the 1970s to the present)

Rather than celebrate this “end of art,” Postmodernist philosophy attacked Enlightenment notions of progress, which it associated with colonalism and patriarchy. The “end of art” wasn’t the end of progress; it was the end of the idea of “progress”. Art criticism began to avoid judgements at all, becoming suspicious of value judgements entirely (as described by James Elkins). As a result, the Contemporary Art world doesn’t aim for progress or try to answer questions about “what is art?”

Contemporary Art is often characterized instead as a “conversation”: a back and forth of ideas. Consider a conversation at a dinner party with a sophisicated group of friends: what’s most important in a conversation is to say something both interesting and relevant. A conversation progresses over time, but it’s not Progress toward an ideal. It’s an activity, not a journey to a destination.

A core value for Contemporary Art is that “an artwork is an expression of an idea”. Within this world, the form can be almost anything, whether abstract expressionist painting (Gerhard Richter), performance art (Marina Abramovic), photography (Cindy Sherman), Appropriation Art (Sherrie Levine), or something new (Ryoji Ikeda), as long as the narrative around the work constributes something interesting to the conversation. Contemporary Art isn’t defined by form or content, it’s defined by it’s status within the community and the conversation. Just making a skillful painting without that narrative isn’t interesting, because we’ve been doing that for thousands of years. Much of contemporary art has abandoned emotional expression, often celebrating work that’s highly cerebral.

Contemporary art has aimed for greater multiculturalism and inclusion, foregrounding work by previously marginalized groups and attacking the masculine stereotypes of Romantic and Modern Art. Contemporary art has also been heavily influenced by the political activism of the 1960s, and become particularly political within the past few years. It has revisited the arts/crafts division and its gendered, colonialist roots, with, for example, feminist artists incorporating textile arts into contemporary art.

I’ve written much more about the contemporary art world.

I see Contemporary Art as just one of many categories we have today; a genre and subculture, foreign to most people in our society. However, it looms large in our discussions of art and what art can be. When we talk about definitions of art, we discuss putting urinals in galleries and taping bananas to walls as important cases to consider in our definitions of art.

These efforts are frequently political and contentious: early attempts by art museums to incorporate indigenous artifacts into their collections, have been criticized for imposing artworld divisions on cultural traditions: why did some indigenous works go to the art gallery and some to the natural history museum? And the whole thing, even more, elevates the Contemporary Art world as the gatekeeper of art when, in effect, it makes the evaluation that “even some tribal artifacts can be art.” Parts of this artworld engage in a seemingly-endless Postmodern conflict between idealism (the Romantic/Modernist ideal of the artist as independent boundary-pusher; the 60s activist ideal), and recognition of the money and privilege that drive art in the real world.

Art in terms of these Four Modes

Understanding these divisions helps understand different notions of art. I suspect one could formulate a pretty detailed philosophy of art by breaking it down to modes according to these four Eras, each of which is relatively definable. Here I’ll call them the Four Modes, since they all coexist in our current era (and often overlapped historically).

Everyday art experience

Most of us live in a world of Romantic and Modern Art (with Postmodern elements): the artist as maverick genius, creating artistic experiences. We consume art for the experiences it creates, how it makes us feel, how it connects us to society and teaches us about the world. We revere our favorite actors, directors, and musicians, with attention and fandom that border on religious. We draw a sharp divide between art and craft. Conceptual art is of relatively little interest to most of us, except occasionally as a funny news item.

Our art is sometimes realistic, but often abstract and non-naturalistic. The forms of most of our art experiences are largely Modernist, but with new technologies for creating and sharing these forms. The most Postmodern aspect of our current moment is the breakdown of genre.

We mostly interpret through a modern lens

We appreciate historical artworks through the lens of our current world. We don’t necessarily care about what the historical artists and their patrons cared about; browsing through Medieval and Renaissance art, we see reference to ancient kings and battles and religious schisms that most of us know nothing about.

First and forement, we appreciate old art in modern terms. Consider this advertisement from The New Yorker:

It uses Contemporary langauge (“claimed … as a legitimate subject of art”) to speak to current activism (“resistance to oppression.”) Arguably, these concepts would have been foreign to anyone living in the Artisan Era—Gentileschi included—when painters were artisans supported by the patronage system. The linked New Yorker article, which is two years older, doesn’t even use this langauge. In fact, the article describes the complexities of her biography that is omitted from simplifying modern narratives.

So many of our modern Art Icons were unknown or marginal in their times—Van Gogh, the Mona Lisa, Frida Kahlo—but then commercially revitalized in ways that smooths out details of their actual stories: Van Gogh the troubled genius who cut off his ear, Frida Kahlo the feminist icon. These Art Icons are mythological characters, like Hercules or Spider-Man, not historical artists. This happens throughout art, e.g., Virgil remixing Greek myth to glorify his emperor and Roman values; the different versions of Alexander Hamilton.

Approaching Contemporary Art for someone with an education that ends at Modern Art causes confusion, especially if one incorrectly assumes that the Contemporary art world still cares about progress and wondering “but is it art?”

I think it’s valuable both to recognize the current lenses by which we understand art, but also learn about the historical stories, e.g., to understand both Frida Kahlo’s life on her own terms but also her new life as a cultural icon, which are two quite different things. History tells us lessons about the messiness of real life, whereas the icons offer simple flags to fly.

Art vs. Craft

As discussed in my previous post, the division between art and craft remains confusing. “Craft” sometimes means “technical skill,” and sometimes refers to a whole range of media that, since the Romantic Era, were considered non-Art.

Nowadays, when I hear someone complain “that’s not art, that’s craft,” I want to point out that this division is only a few hundred years old, a product of the Romantic Era. I think it’s useful to think about artistic expression and technical skill as two distinct aspects of a work, but how can one say that sculpture is art but knitting sweaters or weaving rugs is categorically not? Simply to define an activity as “craft” is to reopen the artificial divide between arts and crafts.

Conclusion

These four Eras/Modes definitely oversimplify, and they’re just one lens on art. But I find it useful as a tool for understanding some the gaps between different art cultures and goals of art.

Thanks to Juliet Fiss and Sibel Adali for comments.