How We Perceive Shape in Painting and Photography: Perspective

In this blog post, I outline a new theory for how shape perception works in pictures, specifically, how we interpret perspective. The ideas I present here can describe, at a high level, how it is that we have so many different ways to make realistic pictures, and that we can understand them. It combines ideas from human vision science, art history, and computational photography.

This post is based on this paper:

| A. Hertzmann. Toward a Theory of Perspective Perception in Pictures. Journal of Vision. April 2024, 24(4). [Paper] [Webpage] |

Pictures convey shape, but why?

We can perceive shape in all different kinds of pictures, from cave paintings to photography to modern art. You can look at this photo:

and have a sense of the scene it depicts, including the shapes of the buildings, tables, and people, and where they are relative to each other.

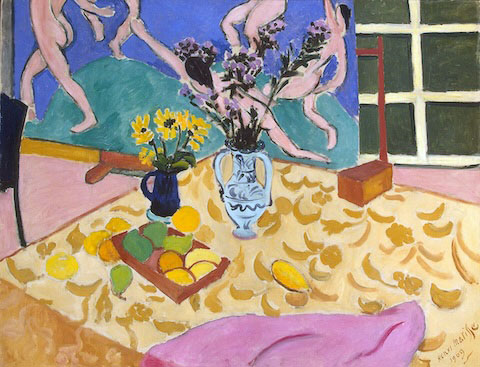

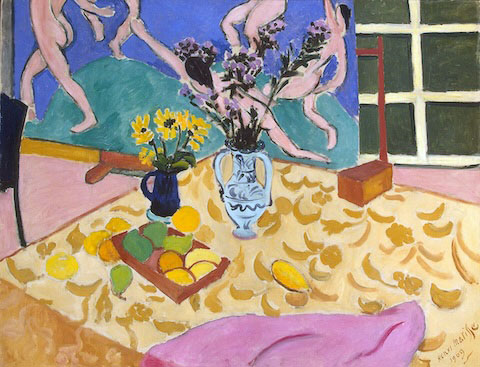

The same goes for all sorts of representational paintings. Here’s a painting by Matisse:

Even though it looks very different from a photograph, you can easily see that it depicts a table with some vases and fruit on it, and you can tell what the shapes of the vases are.

The photograph gives you more precise information than the painting. But both convey something the shapes of objects, and where they are relative to each other and to you, the viewer.

There are many, many other types of painting styles that look different and convey shape differently, but still convey the same kinds of 3D information.

Why does this work? That is, why and how does human vision get a sense of 3D from these pictures? People have wondered this for a very long time. This question has many aspects, but, in this theory, I focus on the geometric relationship between 2D and 3D space—the relationship between the 2D positions in the picture and in their positions in the 3D world that they represent. This relationship is generally called perspective, although that word implies a single viewpoint, and I claim that picture perception does not involve a single viewpoint. In contrast, many conventional theories assume that pictures must be constructed according to linear perspective rules from the Renaissance, but obviously this does not explain the full scope of different kinds of pictures like those above, and even linear perspective pictures create various kinds of distortions.

Foveal and fragmentary vision

Looking at a picture requires moving your eyes around, to look at different parts of a picture. You don’t just download a picture into your brain the way a smartphone captures a picture with its camera. We tend not to pay much attention to this step, but it’s surprisingly important.

Consider this picture, which contains two concentric rings:

It’s hard to tell what’s going on in this picture. Whenever you fixate your eye on one part of the picture, you can understand what’s happening at the point where you’re looking. But the rest of the picture is confusing. Then, if you move your eyes, the same thing happens: the new part is clear but the rest is confusing—even the place where you were just looking.

This picture illustrates several important principles.

The first principle is the foveal nature of vision: we see detail mainly in a small part of the picture around the eye fixation, and the rest of the picture is more vague.

Another way to experience the foveal nature of vision is to fixate your eye on this word, and then try to read other words. While keeping your eye fixated on the word “this,” you won’t be able to read any words except those right around “this.”

The second principle is that vision is fragmentary: we don’t keep detailed pictures in our heads. You might think that you can get the whole picture into your head by moving your eyes over it. Then, one you’ve fixated on enough different parts of the picture, it shouldn’t be confusing any more, and then you can study the picture just by thinking about it.

But this doesn’t happen—the illusion persists no matter how long you look at it. With enough conscious effort, you can work to memorize the elements of a picture, but, even the you may be memorizing a conceptual representation, not a pixel-accurate picture.

Instead, after looking at a picture, we seem to remember some sort of abstracted version of it. Remember that photo of an alley at the top of this post? You can probably remember that it contains an alleyway with people walking on it, and maybe you have a sense of the architecture, and so on. (Feel free to scroll back up to refresh your memory, and then come back here.)

But, once you’ve looked away from it, you can’t recall every detail. For example, how many people in the picture are wearing red shirts? What are the colors of the stools? What are the hairstyles of the two people in the foreground? What letters are visible on the wall to the right? All of these questions are easy to answer while looking at the picture, and impossible to answer afterward, unless you’d made conscious effort to memorizing these particular details.

These two principles—foveal and fragmentary vision—demonstrate severe constraints on how we look at and understand pictures. We understand pictures fixation-by-fixation, one piece at a time. At each glance, we interpret the contents of a picture around our fixation, and then move onto the next fixation, remembering only a fraction of what we saw.

Real-world vision works the same way: we continuously interpret the world at each glance, and update an abstracted mental model of the world as we go. We don’t 3D scan every detail of the world into memory, we store only abstracted representations. In a previous blog post, I discussed more about how real-world vision is foveal and fragmentary, and why. The way we view pictures derives real-world vision.

Fixated-Centered Perspective

So now let’s get back to shapes of objects. What does human vision assume about the projection in a fixation?

A clue comes from perceived distortion: when objects in a picture “look wrong.” Here are shapes at the center of a linear perspective projection that do not look distorted:

These shapes—which don’t come from the center—do look distorted:

(People often use “distortion” to describe camera optics that do not match linear perspective. I do not use “distortion” to refer to optical distortion; I am talking about when things “look wrong.”)

If an object looks distorted, that’s a sign that it hasn’t been projected according to the assumptions of human vision. So when do things look distorted? In a previous blog post, I argued for the general principle that objects look distorted if they don’t look like they came from the center of a linear perspective projection.

Together, these observations lead to a theory that I call Fixation-Centered Perspective:

| In each fixation, a picture is interpreted in terms of a linear perspective projection centered at the fixation. |

In this theory, the distorted basketball looks like a stretched 3D object. That is, this shape in the picture only makes sense as the projection of an ellipsoidal basketball. But then, you can recognize that it’s distorted basketball, and understand that it’s probably a distortion, not an oblong ball. So there are a few things going on in your brain simultaneously: simultaneous perception of an oblong 3D shape, and awareness that it’s probably distortion and not actually oblong.

It’s similar to the way refraction in the real-world distorts how objects look, but we can understand the distortion: the spoon in this glass looks broken, but we know it’s not.

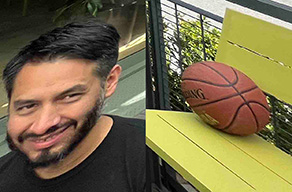

It’s not just about distortion. Consider this wide-angle photo:

When the photo was taken, the people were sitting parallel to each other. But the photo makes it look like they’re facing away from each other.

What’s more, if you crop it to make a new picture containing just the fellow, Jan, on the right:

Then it still looks like he’s facing to the right. So we interpret him as facing to the right—which corresponds to a linear perspective centered on him—regardless on where he’s on the right side of the picture or if he’s the whole picture.

That is, the apparent direction he’s facing doesn’t depend on where he is in the picture; you perceive him according to a linear perspective projection centered on wherever he is in the picture.

(This photo is from an inspirational paper that argued something similar to what I’m claiming.)

Diagrams

Here are some diagrams that might be useful if you’re familiar with perspective projection diagrams.

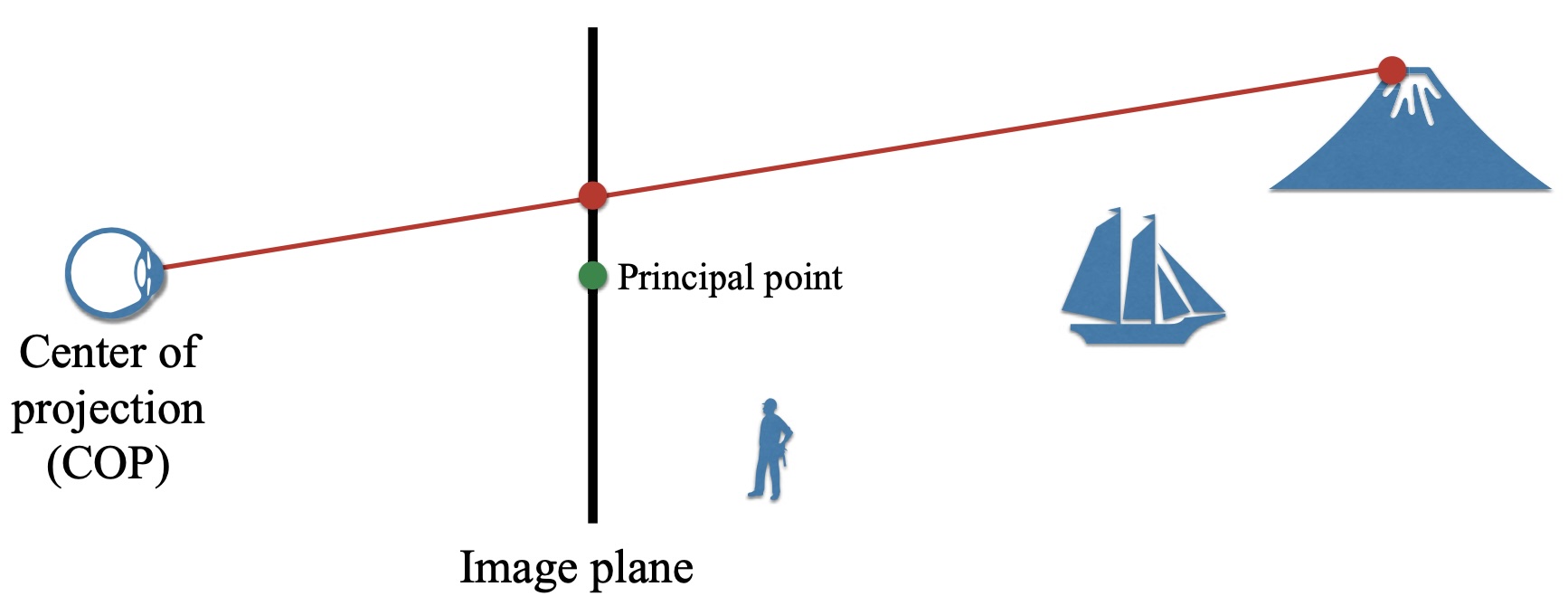

Some classic theories assert that viewers interpret pictures as though they were made by linear perspective projection. In linear perspective, points project from 3D to the image plane along the line that passes through the center-of-projection (COP):

In these theories, human vision assumes that the 3D location corresponding to a point in the picture must lie on a line from the eye to the COP. Since people rarely view from the actual COP, variants of these theories hypothesize that viewers compensate for viewing from the “incorrect” location, but extensive experimentation has disproven these hypotheses.

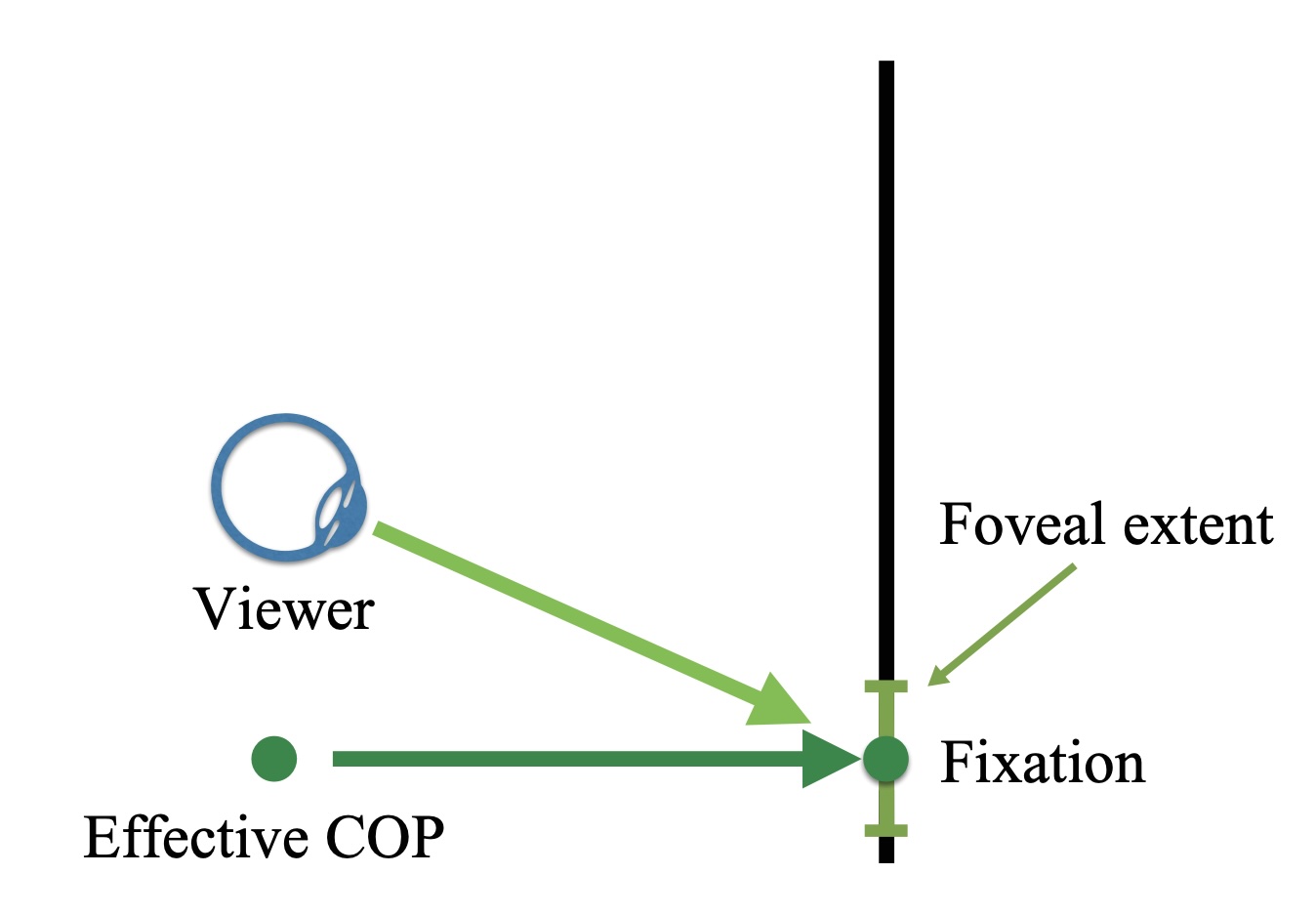

In Fixation-Centered Perspective, the picture seen in any given fixation is interpreted according to a linear-perspective projection, centered on the fixation:

There are a few possibilities for where the effective COP location is: it might be where the eye is, but I think that, in normal viewing (e.g., binocular viewing from a reasonable distance with both eyes open), the implied COP is in front of the fixation.

Scene awareness

So, then, what happens when you look at a picture?

-

You first fixate your eye on one part of it. You get a sense of the detailed shape in the part you’re fixating on, together with a rough, overall sense of the picture (the “gist” of it). In that fixation, you interpret the picture according to a local linear perspective.

-

Then, you fixate on a different part and get information about the new part of the scene. And most of the information you had in that first fixation goes away: you cannot recall fine details you’d just seen, unless you’d consciously studied them.

-

This repeats every time you move your eyes. After enough fixations, you have a general sense of the contents of the picture: what objects are in it, what are their colors, and how are they arranged.

These same basic things happen when we look around in the real world. We don’t store detailed 3D models in our heads of the real world, we store abstracted representations that aren’t even consistent. The fragmentary nature of real-world vision answers a riddles of why pictures work:

| Q: Why can flat pictures convey such effective illusions of 3D? |

| A: Real-world 3D vision is less than it seems. |

To look realistic, a picture just has to make the contents of each fixation look realistic—they do not have to be completely consistent with each other.

A cave painting, a panoramic landscape painting, and a photograph each do these things in different ways.

Looking at art

The main claim of the theory is each part of the picture is interpreted according to its own local perspective—you can cut out part of the picture and the perspective constraints on shape don’t change.

So let’s look back at some art from this post (and a previous one), and see how it fits.

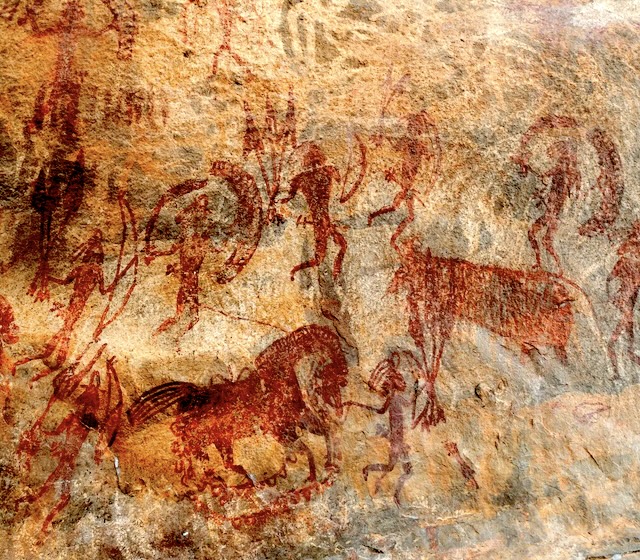

A prehistoric cave painting conveys shape and space in relatively simple ways:

If you fixate on each figure, you can see the silhouette of a person, or an animal. Each figure looks—roughly—like real silhouettes we might see in the real world (e.g., backlit in twilight). You can get a very rough sense of how the figures are arranged in space relative to each other.

Back to that Matisse painting:

The perspective depiction isn’t very precise or photographic. Each object appears to make sense locally, like they were painted separately and arranged together on the table. Compared to the cave painting, there’s just a bit more information about the spatial arrangement. (Some of my own causal drawings end up looking something like this.)

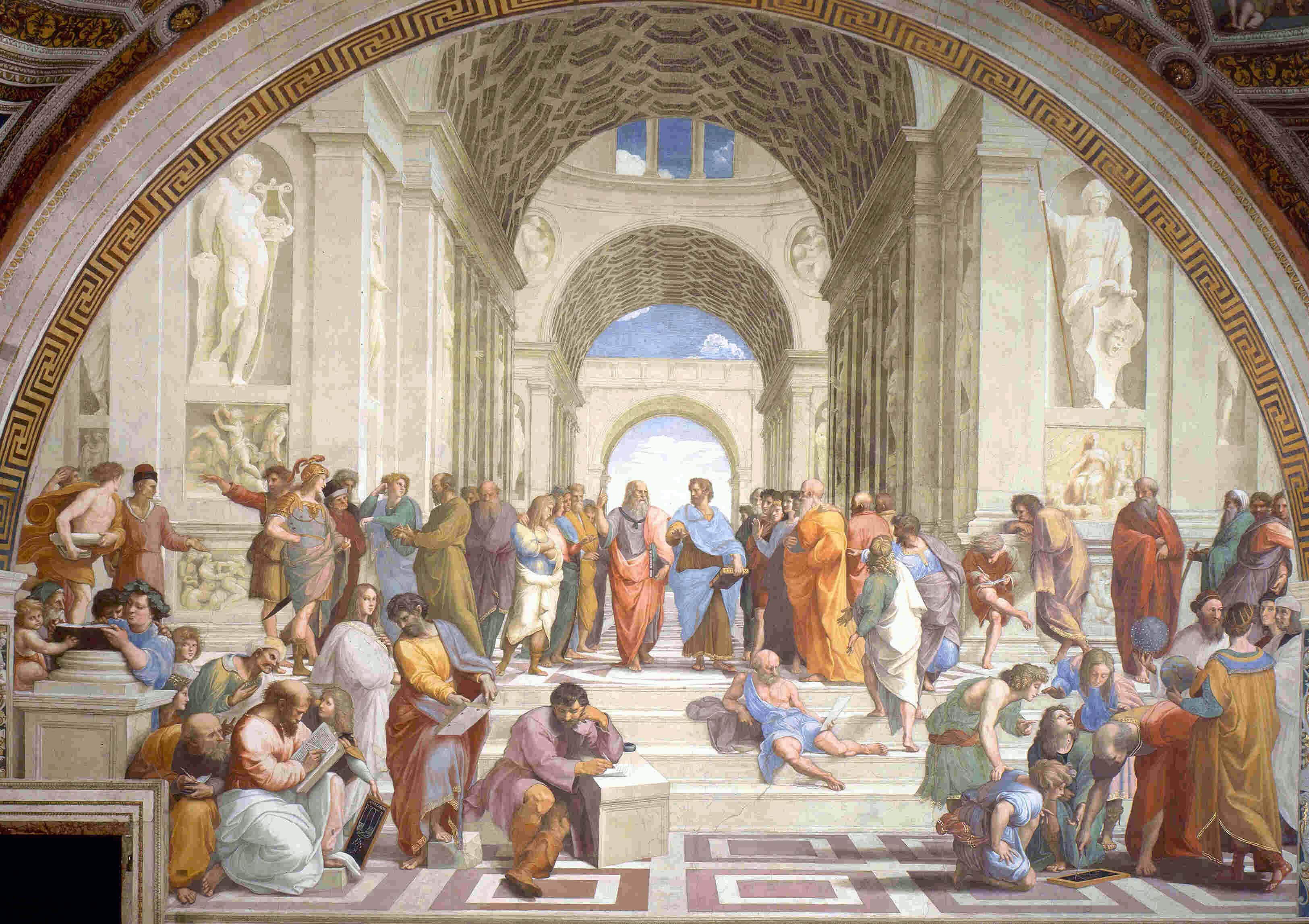

If, on the other hand, we go back to Raphael’s School of Athens:

This theory answers the question asked by past art historians and psychology researchers: why didn’t Raphel draw the people or sphere’s in the corner with marginal distortion?

Fixation-Centered Perspective explains that we perceive the shapes in the corner the same as if they were in the center of a linear perspective projection. We don’t perceive pictures assuming a single linear perspective for the whole picture the way that a lot of art historians and psychologists have assumed.

In this painting—and in any photograph—you can cut out part of the photo, and interpret the shape in that part. Your shape perception in that part alone will be the same with or without the rest of the picture (except in weird cases where the contents of the cut-out are ambiguous or confusing on their own).

Artists in history have used lots of different approaches to perspective. Here’s part of a 12th-century Chinese scroll painting that uses a parallel projection:

We get a sense of people arranged in depth around architure, but the distant people are not smaller than the nearer people, so it’s a bit more like looking down on a tabletop with figures that are all roughly the same distance to us than looking at a big panorama. Each of the people is depicted with shapes roughly like Raphael’s shapes, or the cave painting—they’re not distorted or stretched. Some of the corners of buildings don’t quite make sense for linear perspective, so they don’t quite look like right angles.

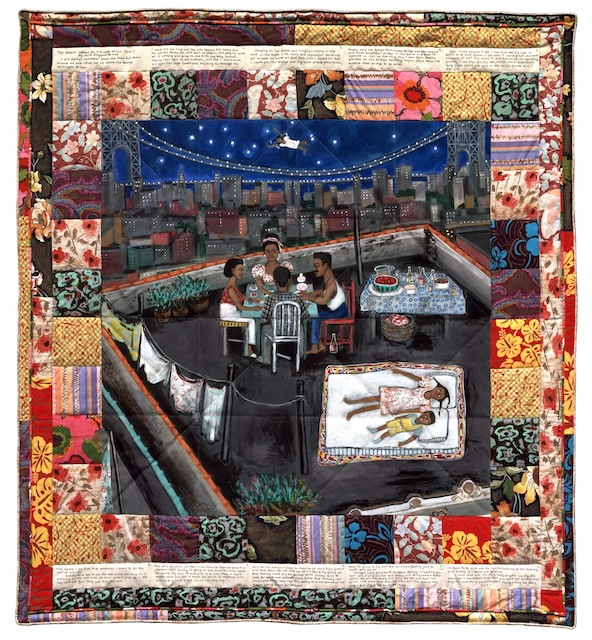

Starting with the Modern Art movement, artists have explored all sorts of different approaches to shape and space in pictures, arranging different perspectives into single pictures:

Each portion of one of these pictures can be interpreted by its own local perspective—which often might be interpretable within one or two fixations—and then arranged in space with varying degrees of precision—precise in a photograph, loose in a cave painting.

This theory fits the evidence well

The Fixation-Centered Perspective hypothesis that I’ve proposed explains a lot about how perspective works—including many phenomena that no previous theory has even attempted to explain.

It’s consistent with (or explains):

- The nature of peripheral vision and fragmentary 3D vision

- The effectiveness of linear perspective

- When distortion is perceived, in all sorts of pictures

- The multiperspective nature of classical paintings

- Multiperspective photography

- Partial perception of 3D in impossible pictures

- Local slant compensation

- Pictures on curved surfaces

What’s more, it’s possible to see from this theory, how picture perspective derives from real-world vision—it depends on the nature of peripheral vision and fragmentary vision, but ends up behaving differently from real-world vision.

We’ve also performed some experiments testing the theory further; these are not yet published.

Future directions

If you’re interested in reading more, you can see the scientific paper, or my previous blog posts on The Illusion of Awareness, wide-angle perspective distortions, the direct view condition for distortion, and/or more peripheral vision illusions.

There is much to do to test and develop the elements of the theory. There are many questions to ask, like, how big a region do you perceive shape in? what information do you get from outside the foveal region? What 3D information do we mentally preserve over time?) To all of these questions, the current answer is “no one knows,” so there’s a lot more work to do.

I plan to develop the theory further—I think it can explain more phenomena, like why distant objects look too small in photos, and what goes on when you draw a picture.

I also believe these ideas could be useful for how we teach art history, computational photography, and studio art—getting away from linear perspective and providing better tools for how to think about perspective and picture composition.