The Illusion of Awareness: Why We See Much Less Than We Think We Do

A few years ago, while walking home, I noticed a dry cleaners across the street from my house. “Was that always there?” I thought, surprised. I’d walked by that spot many, many times over the years, but I’d never noticed the cleaners. A little Googling revealed that it’s been on my street for longer than I have. Yet, if you’d asked me for the nearest dry cleaners near my house, I would have answered that I didn’t know of any.

How could it be that this shop had been in front of my eyes so many times, yet I’d never seen it?

I also recently noticed that the second hand moving on the icon of my iPhone’s Clock app. How long has it been doing that? It turns out that it’s been moving since 2013, and I’d never noticed it. If you have an iPhone, how long did it take for you to notice?

It turns out that, in a sense, we don’t see most of the things in front of our eyes, we only think we do. Here’s my favorite example. If you haven’t seen this video, I urge you to spend a few minutes watching it. Be patient—I promise it’ll be worth it.

When I show this video in my talks, the audience makes audible gasps and “wow”s. Not only do we not notice what’s happening, but we’re confident that nothing is happening.

Here’s a much more famous example that you may have seen already. If not, you really have to avoid spoilers for this one, and follow the instructions carefully—it’s worth it.

Surprising, huh? Why does this happen?

This blog post describes the fascinating, recent scientific explanations for why we fail to see things that are right in front of us. Most of the time, it doesn’t matter that we’re failing to see things in front of us. We might sometimes wonder why we just hunted everywhere for our keys, only to find out they’d been right in front of us. But things I’ll describe have some real implications for many aspects of our lives, and are important to understanding how human vision works. In a later blog post, I’ll explain why I think these things are essential to understanding pictures as well.

Looked But Failed To See

That second video made waves when it came out, and led to a whole body of scientific research on similar illusions. In one study, a researcher stopped a stranger to ask for directions. During a carefully-planned interruption, another researcher quickly swapped places with the first—and the bystander would not notice that they were suddenly talking to a different person.

These effects go by a few names, including Looked But Failed To See. In one important category, inattentional blindness, you are unaware of something that you didn’t pay attention to.

Of course, it’s normal to be unaware of many things—if you come to an unfamiliar, closed door, you know that you don’t know what’s behind it. But, in these Looked But Failed To See illusions, we’re unaware that we’re unaware, and we’re later shocked to discover that we’ve missed something that was right in front of our eyes.

Once I noticed the dry cleaner on my street, I thought, “what else had I missed?” Just looking closely around my home, I could see many details that I’d not noticed after a decade of living there; like the panels of wood that weren’t flush, and odd construction on a railing. Most of these details were insignificant, but it still seemed noteworthy how unaware of them I was after years of living around them.

Often it takes some external push for me to notice new things, like walking a dog, or hosting an inquisitive visitor.

These illusions do matter, though. Radiologists looking at scans might miss visible signs of tumors because they didn’t look in the right places. Eyewitness accounts may be unreliable, in part, not because people are untrustworthy or forgetful, but because they genuinely did not see what was in front of them—and they didn’t know they weren’t seeing it.

One day, I was crossing the street by my house when I saw a car turn left and come right at me. I narrowly dodged out of the way and it screeched to halt… in the crosswalk, where I’d just been walking. When I complained, the driver defended herself with “I didn’t see you!” And, she didn’t seem impaired or dishonest.

What’s going on in these illusions?

Foveal vision

To understand these illusions, we have to first look at the workings of the human eye, and how our minds actively use our eyes to see.

To see one of key differences, try the following. Look right at one of the street signs in the picture below. Then, without moving your eyes, try reading the text on any of the other street signs.

I can’t do it, and I haven’t met anyone else that can. Why is this so difficult?

To see why, we first need to understand the human retina.

It’s tempting to think of the human eye as being like a camera. In some ways, it is. Like a camera, an eye has a lens that focuses light onto an array of sensors. In the eye, this sensor array is called the retina. But there’s an important difference. In a camera, the light sensors are arranged in a uniform grid. In the human retina, the sensors (called “rods” and “cones”) have a much more interesting pattern.

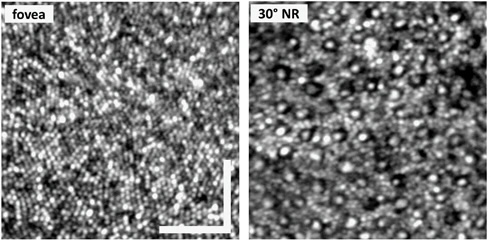

Here are microscopic images of two parts of the retina. On the left is the center of the retina, which is called the fovea:

The fovea is densely packed with cones, which measure light under normal conditions. On the right, another portion of the retina (at a 30-degree angle from the gaze direction) has sparser cones, and is mixed in with the larger rods, that primarily operate in low-light conditions.

It’s a bit like a camera sensor that captures high-resolution at the center, and has fewer and fewer pixels the further you get from the center. Moreover, as I’ll explain later, our brains don’t keep all the “pixels” outside the fovea. Instead, brains summarizes them with statistics.

These two facts together mean that we can’t recognize things nearly as well outside the fovea as inside.

Eye movements

If our eyes were just like normal cameras, we wouldn’t need to move our eyes much: they’d just look forward and soak in all the light like a surveillance cameras. But they’d be very low-resolution. We wouldn’t be able to read distant street signs or otherwise see things well at a distance.

Here’s a panoramic picture of a street, that, like human vision, covers a little more than 180-degrees horizationally:

The red box shows where those street signs from before. When I took this picture, I could easily read each of those street signs by looking right at them. But they’re so tiny in the panoramic photo that you can’t even see them, much less read them.

This illustrates how foveal vision allows us to have very high-resolution vision, but only for a very, very narrow range of directions. The range of directions that our eyes see is called the visual field, and foveal vision covers only 0.01% of the visual field (roughly 1 degrees horizontally, although some people define the fovea as being 5 degrees). If we did have full resolution everywhere, instead of foveation, then our brains would have to weigh thousands of pounds to process all that information.

And so, to perceive the world, we move our eyes around. We look at one thing, then another, then another. As you read this text, your gaze jumps from word to word. When looking at a photograph, your eyes jump around from point to point. For the most part, this happens unconsciously—we may not even be aware of our own eye movements until it’s pointed out.

So, here’s a clue to the illusion videos at the beginning of this post. In the first video, you can see changes only when you look right at them. In the second video, you can see the gorilla only when you look right at it.

Peripheral vision

It can’t just be about the fovea—all that other vision must be doing something too.

The rest of the visual field is called peripheral vision. That name is misleading: it sounds like it’s just what we see out of the sides of our eyes. But the term “peripheral vision” refers to 99.9% of the visual field—nearly all of it. The fovea is just the tiny little bit in the middle where we do most of our looking.

What information do we get from peripheral vision, and how do we use it?

The nature of peripheral vision is subtle and easily misunderstood. In the research community, we often talk about it like it’s just blurry vision. But it’s not. Here’s an illustration of why.

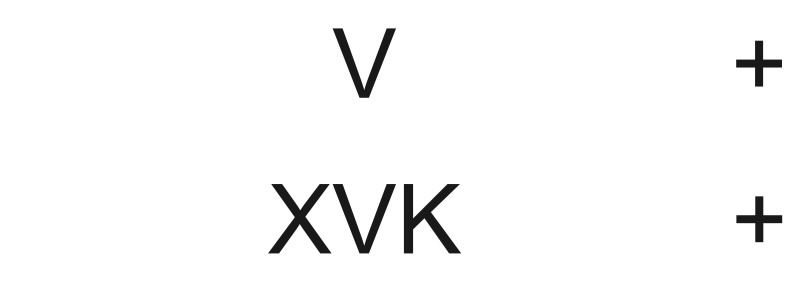

Stare at the top cross (+). You should be able to recognize the V to its left. Now, what happens if you stare at the lower cross? Now the V to its left itsn’t recognizable, because it’s in-between the X and the K. People viewing just the bottom cross might see a jumble of letters to the left.

So this isn’t just about blurry vision—it’s the crowding of the letters that make it hard to recognize them. The brain encodes peripheral vision with statistics, and these statistics get muddled with crowding. One letter alone on a white background is easy to recognize, while the other letter surrounded by others is hard to recognize.

Why We Look But Fail To See

We notice things that we look right at, and peripheral vision helps us decide where to look.

If you’re hunting around for a red keychain, you’ll be attuned to finding red things in your peripheral vision. And, if there’s suddenly a big thing in your peripheral vision, getting bigger very quickly, you’ll urgently look that way to make a split-second decision about whether to dodge it.

In the 2020 paper that inspired my interest in this topic, Ruth Rosenholtz of MIT argues that many of kinds of surprising phenomena, like the ones I’m describing here, come from the limitations of peripheral vision.

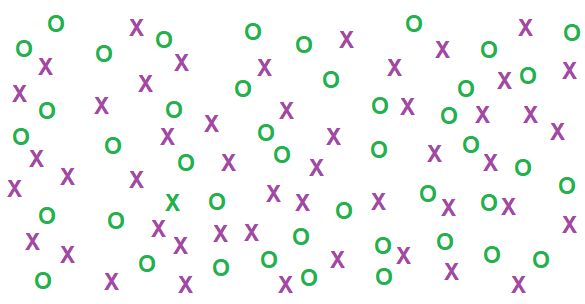

Visual Search is a key example of the role of peripheral vision. Let’s see how the sensitivity to clutter (the XVK example above) affects searching for things, like your keys.

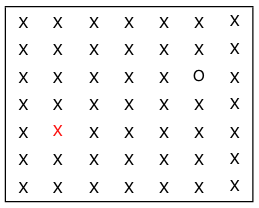

First, there’s a red X in the following picture. How quickly can you find it?

Finding the red X is nearly instantaneous, because the red color is highly salient in peripheral vision: it “pops out.” The shapes of the letters don’t matter.

Now, there’s a green X in this figure. How quickly can you find it?

Now it’s much harder: to find the green X, you need to search carefully over the image. The color doesn’t help, because lots of O’s are green too, so there’s no color difference to pop out. So this might as well be a monochrome image with lots of clutter.

This means that, if you’re looking for your keys, you’re going to have a much easier time finding them if they have something bright red attached to the keychain, and they’re sitting among a bunch of gray objects. Metallic keys on a bunch of gray clutter are much harder to find.

If you’ve found any typos in this blogpost, then that’s another example of something I missed despite having proofread it several times.

Some other phenomena

In this spirit, here’s how knowing the limitations of peripheral vision can help explain some of the phenomena I’ve already described:

-

First video (changing room): In the first video, you can see the changes only when you’re looking at them. Peripheral vision is not sensitive to such slow, subtle changes.

-

Second video (passing basketball): When you’re carefully following the basketball, almost everything else is in peripheral vision, where you don’t notice relatively subtle changes.

-

Dry cleaners: I’d certainly seen the dry cleaners’ building by my house many times over the years, but I’d apparently never read the signs out front. The building is relatively nondescript and blends in with the adjacent houses, and the signage isn’t prominent and had apparently disappeared in my peripheral vision. (It’s also possible that I had read the signs, registered them, but not remembered them, but I don’t believe this.)

-

Driving: People make mistakes when driving, sometimes causing car accidents; one reason is the failure to “see” important things in peripheral vision. When that driver that almost hit me, I was wearing dark clothes on a rainy day. So, if she was distracted or not paying attention to where she was going, then I might have been hard to see in peripheral vision. “I didn’t see you” was a way of saying “I didn’t look directly at the crosswalk before driving into it.” I don’t remember why I saw her coming, but, most likely, I’d been looking around as I crossed the street, not trusting all drivers to be fully alert.

A few times in the past, I’ve fallen into the trap of looking at my phone while biking or driving. I told myself that I’d still be aware of the road because I was keeping it in sight above my phone. Then I’d look up and realize that I’d had no idea what had happened on the road during that time—a chilling thought.

-

Infographics. The way that we understand charts and infographics also depend on awareness; researchers have shown change blindness effects for infographics.

-

Memory-related phenomena. Additionally, our visual memories exhibit similar phenomena, including change blindness (like the changing interviewers), and the Visual Mandela Effect which involves shared, specific false visual memories of logos. Or, consider the myriad shapes people drew when asked to draw a bicycle from memory. In each of these cases, we are wrongly confident of a visual memory.

These examples might be due to peripheral vision (not having registered all the details of a shape or scene, but thinking we have), memory (misremembering details), or some combination of the two.

Why does the brain do this?

Where do these illusions come from? Why don’t we just see things “correctly”?

To answer this question, we first must start with a more basic question. Why do we animals have brains?

A species only needs enough sensing and reasoning to take actions. Plants have no motor control, so they don’t have brains. They do have simple sensory systems, so that, for example, they can grow and reposition in response to sunlight. Another interesting example is the sea squirt, an animal that migrates only once in its lifespan, in order to find a rock to perch on. One perched, it will never move again in its lifespan, and so its motor nervous system dissolves, that brain no longer being needed. This process has been jokingly compared to middle management and academic tenure.

Likewise, an animal’s senses depends on its unique needs. Birds see far more types of colors than we do, in order to distinguish the flowers they care about. We humans experience the world differently from plants or birds or sea squirts, because we have different sensors (an idea expressed in the concept of the umwelt). We can’t fully know what it’s like to be a bird or a dog, in part, because we sense different things than they do. A sidewalk that seems ordinary to me might present a magnificent smorgasbord of fragrances to a dog.

When I first learned all this theory, it all seemed very abstract—what does it have to with our real experience? We think we “see everything” around us. Yet, it turns, out that we have these massive blind spots, figuratively speaking, that are subtle and hard to understand.

Costs and benefits to the brain

Why not just capture high-resolution imagery from the world, instead of our selective foveation? Why don’t we have retinas densely covered with sensors, instead of only getting fine detail in the fovea? We could, hypothetically, get so much more information with retinas that are dense everywhere—all fovea, no periphery.

There’s a trade-off because bigger brains are more expensive. Roughly 20% of the energy we burn to survive goes to our brains, even though they comprise only 2% of our body mass. And, the more connections we have in our brains, the bigger our brains must be, and the harder it is to grow and develop.

So our brains need to be efficient. While we’ve evolved many general-purpose abilities, there are others where we’ve economized.

Consider the problem of vision in a dense and complicated world. We simply can’t gather and process all the light that’s out there—we have to be selective. And, rather than evolving omnidirectional cameras in our heads, we have eyes that we can point at things: look at one thing to study it, then move your eyes to study the next thing. So eyes can do a lot of their vision in a narrow field-of-view.

But we still need peripheral vision—if we only had tunnel vision, then we wouldn’t have any awareness of the world around where we’re looking. Peripheral vision provides context, to helps figure out where to look, and warns of oncoming threats.

Our Pleistocene ancestors would have needed to track predators and prey, forage for food, and engage socially with other humans. Our vision system is good for these tasks. Our ancestors did not need to drive cars in busy roadways or detect gorillas hidden in crowds.

Moreover, our ancestors lived in a world in which rooms did not slowly change, and people in conversations did not sneakily get replaced as part of scientific studies. Our ancestors could generally assume things were constant when they did not undergo big changes, and so our vision systems do as well. And, so, they did not need to mentally store detailed 3D models of the world. In the words of philosopher Alva Noë, “Why should the brain go to the trouble of producing a model … when all the information you need is available, when you need it, by eye and head movements?”

These phenomena, like other visual illusions, demonstrate how much of our awareness is a perceptual construction of reality, an interpretation that the brain builds.

I like this animation as a loose metaphor for this construction:

But it’s not sinister. The unconscious mind creates an illusion for our consciousness, misleading us to think that a narrow perceptual funnel represents total awareness, out of necessity. (Also, the idea of a mental “theatre of consciousness” can’t really explain consciousness, since it kicks the can down the road: how does consciousness work for the guy inside watching the show.)

Looking carefully

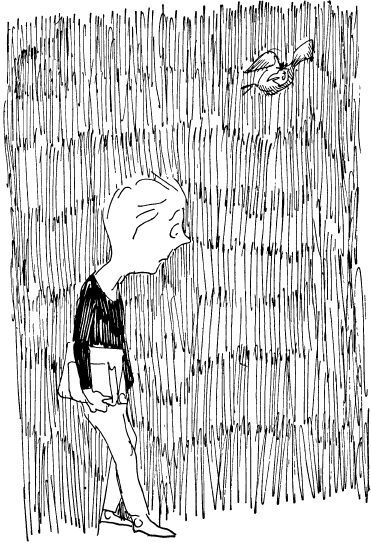

The opening of The Phantom Tollbooth stuck with me from when I read it as a child. It describes a boy who, alienated from the world and from life, “hurried along (for while he was never anxious to be where he was going, he liked to get there as quickly as possible),” and, “without stopping or looking up, rushed past the buildings and busy shops that lined the streets.”

It’s easy to rush through the world without looking, and, thus, not seeing. If we stop, and take time to look, to move our eyes around and study details of the world, to see each of the leaves on a houseplant, or the pattern of waves hitting the shore.

If you haven’t, I recommend trying this in a familiar street, or at home or work: look around in places you wouldn’t otherwise look. Look at each building, look at details in the pavement, or the way your floor meets the walls. I don’t promise that you’ll discover anything interesting. But you will see lots of new things you never noticed before.

Drawing and photography make you look differently

I love visiting New York City and experiencing the dense urban texture, a messy palimpsest of years of construction, businesses that come and go, and people leaving their marks. Each storefront and patch of sidewalk feels like it could be a separate bit of collage art that no single artist could have put together on their own.

One day during my final year at NYU many years ago, I wandered unfamiliar parts of the city with my friend Ted. I had just bought a new digital camera, and actively looked for things to photograph with it. My photos from that day include all sorts of odd urban details like electrical boxes above subway stations and layers of graffiti on a traffic barricade. Such visually fascinating details are easily missed. In fact, it’s absolutely impossible to take in even a tiny fraction of them—but each one I stop to notice feels like a little discovery.

The practices of drawing, painting, and photography train you to look carefully. When you look around for things to draw or photograph, you look differently, more carefully. When you draw or paint from life, you study the appearances of things in a careful way that you wouldn’t otherwise. It forces you to see things you might otherwise pass on by.

Here’s a little drawing I made in a cafe several years ago. It has lots of little details that I wouldn’t have remembered had I tried to draw it from memory, in part because I wouldn’t have noticed them in the first place, nor could I have remembered all of them.

Although it might be more about memory, it’s also fun to see what happens when people are asked to draw a bicycle from memory; and when these drawings are made into 3D models.

Further reading

This blog post is based on the following scientific papers, and the body of literature that they cite:

-

Ruth Rosenholtz. Capabilities and limitations of peripheral vision. Annual Review of Vision Science, 2016.

-

Ruth Rosenholtz. Demystifying visual awareness: Peripheral encoding plus limited decision complexity resolve the paradox of rich visual experience and curious perceptual failures. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 2020.

-

Jeremy M. Wolfe, Anna Kosovicheva, and Benjamin Wolfe. Normal blindness: when we look but fail to see. Trends in Cognitive Science, 2022.

In this paper, I argue that these phenomena post are essential to understanding how realistic pictures work:

- A. Hertzmann. Toward a Theory of Perspective Perception in Pictures. Journal of Vision. April 2024, 24(4). [Paper] [Webpage]

I discuss this theory further beginning in this blogpost.

Thanks to Ruth Rosenholtz for comments on this blog post.