Technology and Social Isolation: From Cars to “AI”

In this blog post, I tell a story of how some technologies from the past century or so have, overall, led to increased social isolation in the United States, as we replaced in-person social interactions with technology.

We can divide social relationships into three categories: close ties, like close friends and family; weak ties, like coworkers and casual friends; strangers, like people you might pass on the street. All three kinds of social relationships are important, and this post is about ways that technology has transformed each of them in the past century.

Technology often benefits our social relationships, in ways that are often obvious. The negative effects are less obvious, which is why I focus more on those. I use and enjoy every category of technology discussed in this post: I love listening to recorded music; I use my smartphone and/or laptop all the time; I love connecting with friends and colleagues on social media. I don’t believe any of these technologies are “bad,” but they are not “neutral” either.

Many different trends inspired me to write this post. The past decade has seen a lot of simplistic claims about new technologies being good or bad. Simplistic arguments over technology as good or bad themselves are harmful because they occupy resources and attention, distracting us from the underlying problems. In my work I’ve tried to understand if these arguments make sense, and, the more I’ve dug into them, the more complexity I find, but also common themes. I’ve previously written about the social nature of art and how it impacts the role of computers as art technology, and the effect of recorded music on social interaction; here I consider other technologies’ effect on social relationships. Most directly, this post is a response to simplistic claims like “social media causes mental illness”. Social media has its problems, but the story is a lot more complex than that.

Cars: from villages and cities to highways and suburbs

Automobiles are the Original Sin of 20th-Century American social isolation.

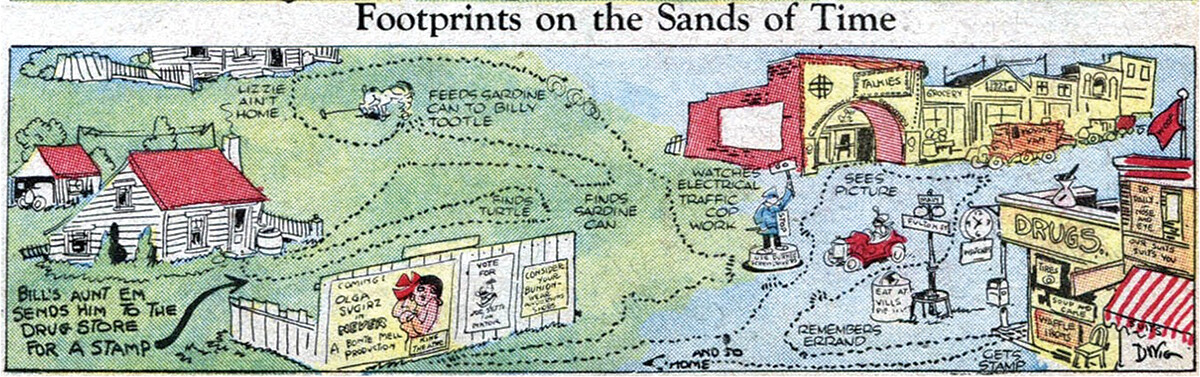

Isolation always existed throughout history. But, by the end of the 19th century, many people many lived in communities where they saw their families, friends and neighbors as part of their daily lives, whether farming villages or larger cities. Even poor immigrants overcrowded into New York City tenements often lacked basic needs but frequently had each other.

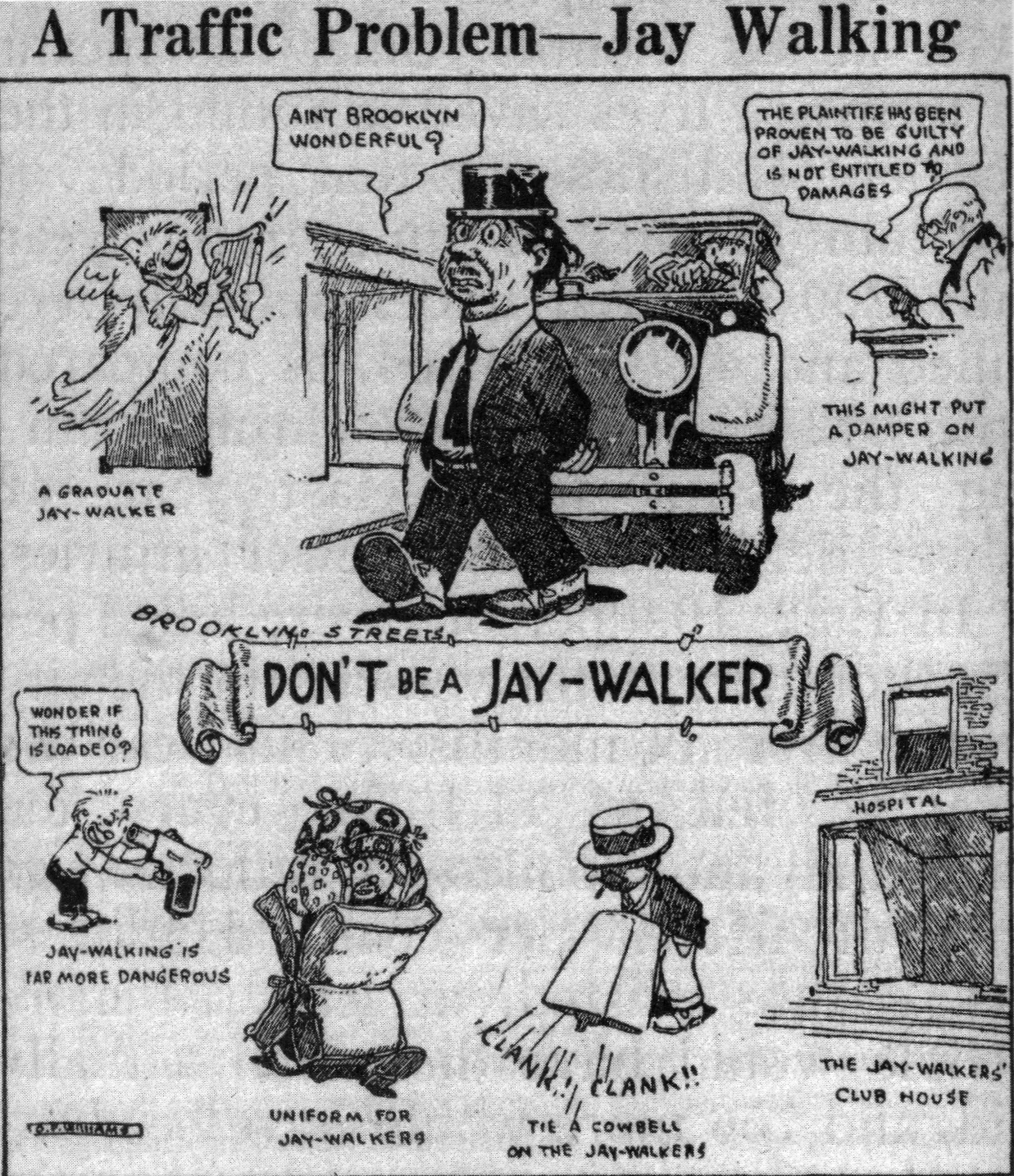

Henry Ford’s invention of the mass-produced automobile—and the powerful automobile industry that grew around it—radically affected the 20th century development of American cities. Before the rise of the car, city streets were public spaces for everybody: pedestrians, horses, children playing. Automobile manufacturers began a program of remaking cities for cars, through ad campaigns to stigmatize pedestrians in roads as “jaywalkers”, lobbying for laws against jaywalking, and lobbying for more roads. (“Jay” is old-fashioned slang for a country bumpkin; calling someone a jaywalker is like calling them an idiot.) Public transportation and walking became less-and-less practical, leading to a vicious cycle: more and more people drove cars, and then demanded more roads. And, when cars hit pedestrians, pedestrians were blamed.

Automobiles offered freedom and independence: convenient ability to travel far, whether for work or reaction. They signalled social status, wealth, independence, and manhood. They became popular, and then mandatory.

By the 1940s, a generation of urban planners favored cars as the primary mode of transportation. Most famously, New York’s transportation overlord Robert Moses grew up wealthy and never learned to drive, yet rode in cars his whole life. He built a staggering number of roads, highways, and bridges around New York City and Long Island, while blocking decades of public transportation projects.

Throughout the US, a new kind of population center arose: the “suburb.” Suburbs allow people to have big houses outside of the cities where they worked. Zoning separated houses from businesses, and large houses were separated from each other, creating massive urban sprawl, and making driving mandatory for most activities in many suburbs.

In the 1950s, federal funding such as the Federal-Aid Highway Act led to the construction of highways throughout US cities. Many cities drew highways right through urban centers, often destroying vibrant communities (often, poor and/or Black) and creating urban blight. Now, some cities devote an enormous fraction of their space to parking lots—some cities have more parking than housing.

By the 1970s, the terrible consequences of our car-first policies were clear: intense traffic jams on highways; smog that considerably shortened peoples’ lifespans; racial segregation; urban blight; unhealthy lack of exerise when people drive everywhere; dependence on foreign oil, as highlighted by the 1970s energy crisis.

Since then, we have undone some of these ills. Emissions regulation mostly eliminated smog; alternative energy modes have reduced dependence on oil; many cities now favor mixed-use urban planning, while investing in bike lanes and public transportation. A few urban highways have been removed, like San Francisco’s Embarcadero Freeway and Seattle’s Alaskan Way Viaduct. But the flywheel of highway demand still drives much of the politics: car drivers, stuck in traffic, continually demand more road in the intuitive but utterly wrong idea that adding roads reduces traffic, and fight against any attempts to share the roads with more-efficient transportation modes.

Car culture and social isolation

But when it comes to social isolation, I think most people still don’t realize just how much our car-first culture has hurt our connections with other humans.

After all, cars seem empowering: if you want to go see friends, go to a restaurant or bar, go to see live theatre or sports… why, you just get in your car and drive there. The car makes it possible! But American urban planning made the car necessary for most of these activities.

Car-first culture reduces meaningful encounters with strangers. As Joe Keohane describes in the surprisingly-deep The Power of Strangers, interacting with strangers and acquaintances creates a sort of societal glue: not only can it improve your own mental well-being, and help you make connections, it ties us together in a community. Even walking down the street, you have passing interactions with strangers; depending on how segregated the society is, you could be passing a cross-section of humanity. It’s much easier to feel some level of empathy for people that you interact with casually, in person. Interactions with strangers has played an important role in human evolution and in many ancient cultures.

When we travel by car, we self-segregate ourselves from all other humans, with virtually no direct interaction beyond fleeting eye contact. Our interactions with others often create stress, and more anger than empathy.

For most of human history, social interactions outside of the home was built into daily life: daily activities naturally involved seeing people. In the suburbs, you can drive to places to interact with people, say, driving to churches, meetups, bars, or public events. You have to make an effort to have interactions with people, as a separate part of your day. Like driving to exercise at the gym.

My father was born in San Francisco, as was his father. After World War II, they moved to the suburbs, like many of that era. My father stayed in the suburbs until retirement, and then moved into a retirement community back in San Francisco. He said ruefully that it was the first time in his life that he felt like he lived in a “neighborhood:” a community where he interacted frequently with his neighbors.

Many seniors choose to stay in their suburban homes throughout their old age, becoming increasingly isolated as their mobility diminshes, leading to increased loneliness, in turn, worsening dementia and other health problems.

Social isolation is particularly bad for children, as I’ll come to in a bit. But first, some parallel developments in entertainment.

Entertainment: From performance to recordings to video games

Throughout most human history, social groups made music together: families played instruments together in their living rooms and porches; city dwellers sang together in taverns; churchgoers sung hymns and gospel together.

In fact, social musicmaking predates human history. Savage et al. survey a range of anthropological evidence that social bonding is the reason why we have music. Music performs important social functions for how we relate to our fellow humans around us.

At the start of the 20th century, Edison invented the first music recording device: the wax cylinder. You no longer had to be in the same room as a performer to listen to music. Recorded music grew in popularity, and, through many formats since (tape reel, vinyl record, cassette tape, DVD, mp3, streaming), remains a huge force in our culture today.

Recordings allow you to develop a sort of relationship with a performer. Sometimes we feel like they’re directly communicating with us. It’s a one-sided, parasocial relationship, but a relationship nonetheless.

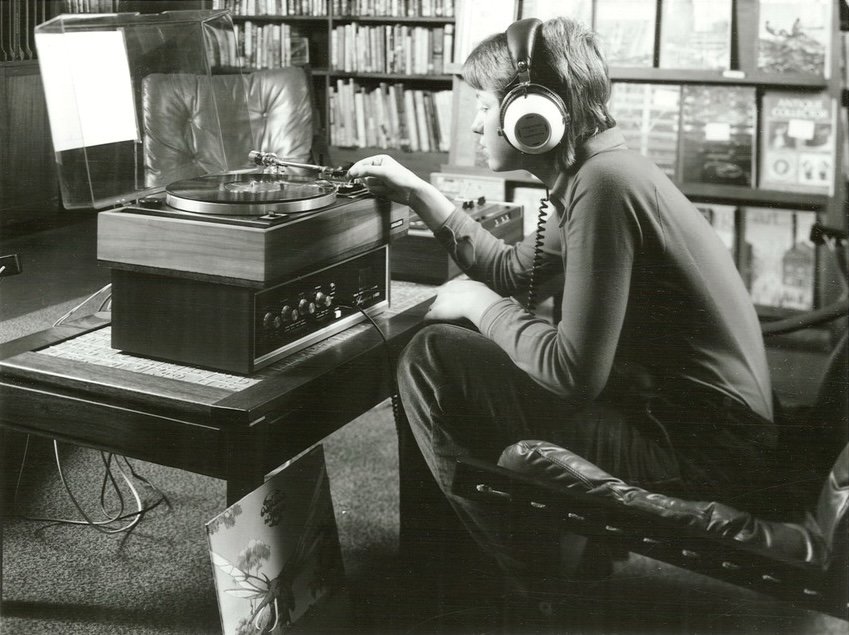

With the development of music recording, radio, cinema, and, then, television, communal music-making diminished. Why go through the trouble of learning instruments, getting your amateur friends together, picking a song, and playing it, when you can listen to a recording of some of the best music in the world? Or watch amazing artists perform on television or online?

Many 19th-Century living rooms focused on a piano. By the time I grew up, most living rooms were focused around the television; the living room of one of my high school friend’s centered around an enormous television that we called “The Shrine.” Watching television together can still be a communal activity. Sometimes the show is a reason to get together. But you can also enjoy music and TV alone.

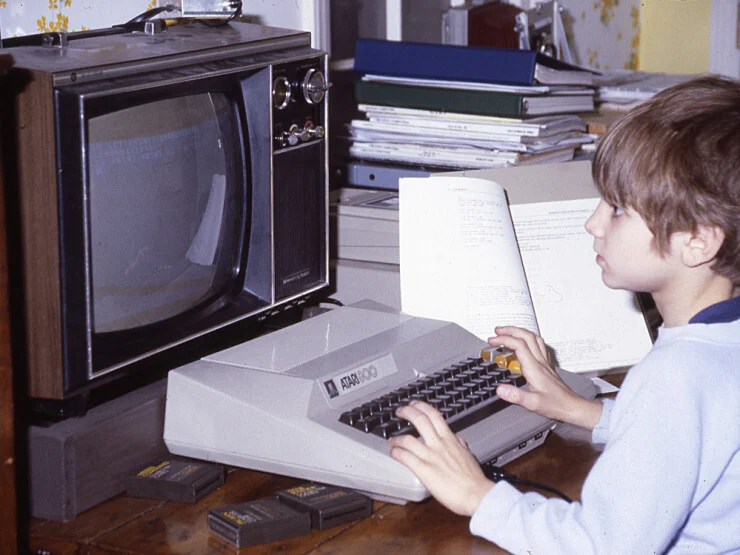

Around the 1980s, home computers and video game consoles appeared. These could also be social—going to a friend’s house to play games together—but one could also spend many hours alone with computers and video games. You no longer needed another person with you for playtime; the computer could be your play buddy. In the suburbs, this was a whole lot easier than actually finding a friend in person. Online gaming and the Internet added social elements, with email, BBSes, Usenet, and then the Web. So you could socialize and play alone, or with friends and strangers online.

With the Sony Walkman, recorded music went into our pockets, we could be out and about, with headphones separating ourselves from the world.

In the early 2000s, computers went into our pockets: with mobile phones, and then smartphones. Now each person carries their own television, cinema, game console, and Internet device around in their pocket. Each person at home or out and about can be in their own separate world of games and passive entertainment.

Children: From free range kids to social media

Let’s come back now to the car-first suburbs, and its effect on children.

As I understand it, children in pre-1970s villages and big cities used to roam freely together for unsupervised play and exploration. Think of the adventures of Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer, or so many other fictional children that explored and played outdoors, unsupervised. The suburbs made this increasingly difficult for many kids.

As a suburban Gen X-er with working parents, I was a latchkey kid who, every afternoon, came home from school alone and stayed at home alone until dinnertime. My closest childhood friend lived over a mile away from me, which, for a kid, was quite a long distance. So we saw each other some days and not others. My other friends lived even further away, and it’s hard to be close with someone you don’t see often. I had a bike, but no interest in using it, which I attribute to a lack of role models, since adults never biked.

My social circle only became really active toward the end of my childhood, once we were old enough to drive, and suddenly groups of us could go do stuff together most evenings and weekends.

A series of “stranger danger” panics made things worse. We were told not to talk to strangers, who might take us away in a white van for unspoken purposes. In essence, we were taught to see every stranger as a mortal threat. But the threat was vastly overstated: stranger abductions were quite rare, much rarer than children dying in car crashes.

Yet, this perceived threat led to seismic shifts in childhood for generations of children. Because of “Stranger danger” fears, millenials were often not allowed out unsupervised alone at all, while helicopter parenting led to a decrease in unsupervised play time entirely. A compelling article by Gray et al. (official link) surveys extensive sociological and psychological evidence that losing unsupervised play time led to an increase in mental illness among millenials.

Children raised in a bubble will struggle outside of the bubble, sometimes for their whole lives.

Since millenial kids had less opportunity to socialize in person, they turned to early social media sites like MySpace and Facebook. Parents responded with another moral panic, fearing the effects of social media on their kids. But, as danah boyd found in her ethnographic studies, these kids were just playing out all the usual teenage social dynamics online. In this case, technology replaced many of the social interactions that these kids were denied in person.

Internet: From social media to “AI”

In the 2000s, social media—Facebook, Twitter, Instagram—became one of the main ways that we interacted with other people in society. More and more, we interacted with our friends, with strangers, even with celebrities online. As newspapers fell to the one-two punch of private equity and Internet competition, we began to get more of our information about the world from social media sites.

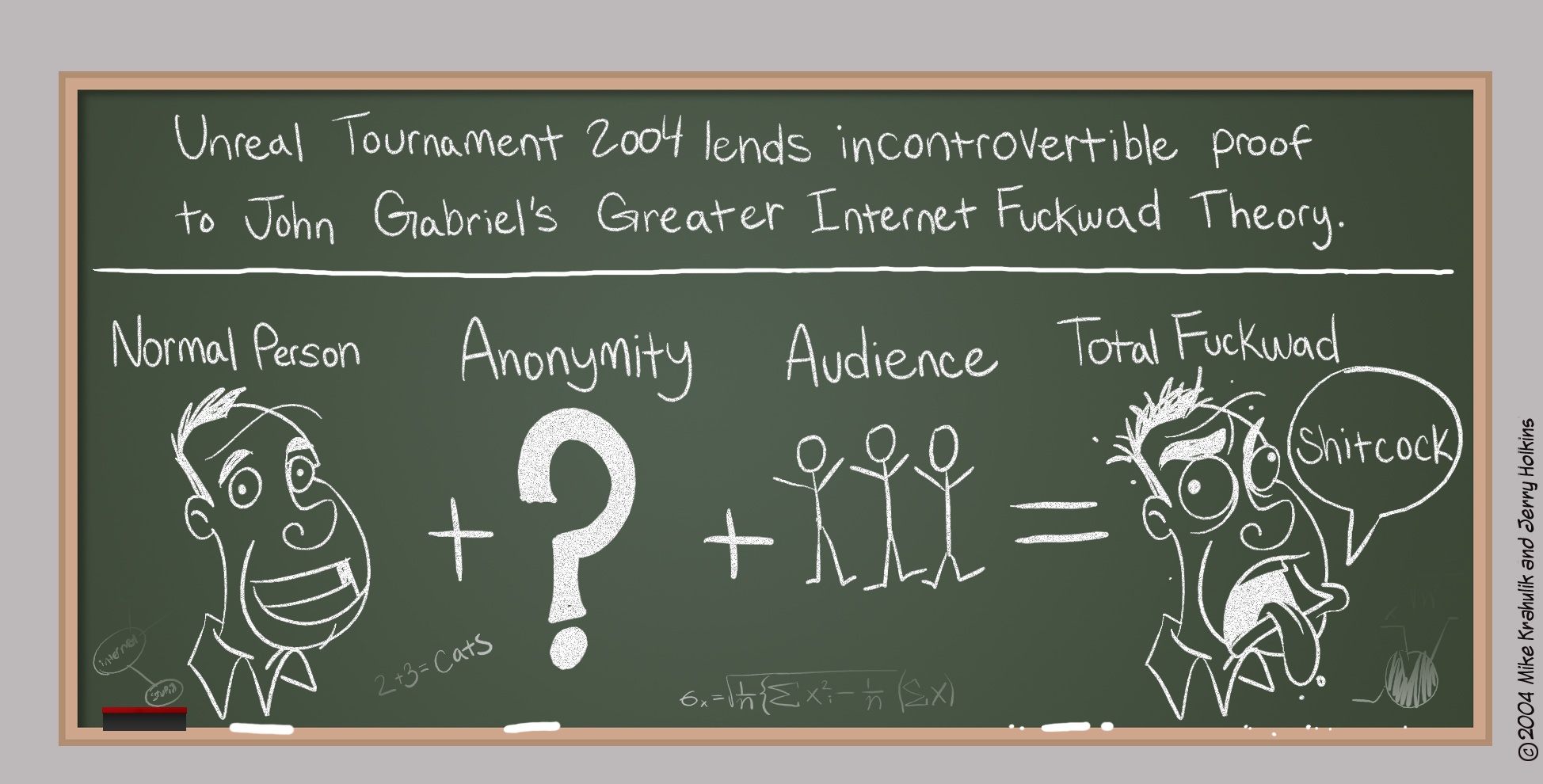

Online affordances have long been blamed for a lack of online civility:

When you don’t see someone in person, it’s harder to have empathy for them. It’s hard to communicate in a considerate way. It’s easier to be misinterpreted. And it’s a continuum: a Tweet is worse than a Zoom call, but a Zoom call is still worse than physically meeting in person.

By the 2010s, America’s polarization reached a crisis level of dysfunction, and many people blamed polarization on social media. I blame propaganda machines (Southern strategy, talk radio, Fox news, etc.), but social media really greased the wheels. In these semi-anonymous online services, messages from your neighbors, from people who share your own values, from political operatives, and from Russian state sources could all look the same and carry the same weight.

By the COVID lockdowns in 2020, we had adopted online technologies so thoroughly that it was fairly straightforward to retreat indoors and conduct all of our interactions with other humans electronically. Electronic communication became a life-saver, literally. But we suffered for the isolation, especially children. And, when we did see each other in person during the pandemic, and, then, when we first came back out into world, to our first restaurants, concerts, and parties, we briefly felt just how valuable and important it was to be out with other people.

As someone who has worked in “AI” research for many years, I find the new technologies amazing and wonderful; it’s so cool and fascinating that they work. A few of the times I’ve tried it, ChatGPT has given me correct answers to questions where all other avenues I’d tried had failed. I’m excited about the way new technologies continually revitalize art.

But new “AI” technologies also extend and amplify all of the threats to our social relationships, mental health, and social fabric. In the most basic sense, even casual interactions with customer service is being replaced by chatbots. We hear of professional writing often replaced by text generation (e.g., scientific paper reviews, law briefs); professors get messages from their students that look like personal communications but were obviously written by chatbots. Even more, we’re hearing stories of people forming intense personal relationships with “AI” chatbots—in a sense, fully replacing human interactions with technological interfaces.

More and more, we won’t even know if the words and conversations we see online were written or spoken by a person, further diminishing our trust and sense of connection to the people in our society.

Does modern technology generally lead to isolation?

Did all of these technologies make us less social? Are there any common lessons and themes? Do automobiles and social media have anything in common?

First, it’s worth repeating that technology does not cause isolation. Technology does not cause anything. But it shifts the scales of what is easy and what is possible.

Moreover, it’s worth repeating that these technologies have a complex impact on our social relationships. If you live in a suburb, then having a car will be very important to having in-person social relationship; you can’t get by without it. So, in that immediate sense, having a car enhances your relationships. Likewise, social media lets you connect with friends and family in a way that you might not otherwise, especially when you live far apart from them. But, by virtue of making it easy to connect when we live far apart, they make it easier to live far apart, creating a vicious cycle.

As technologies get better, they automate many interactions that previously required a human.

A 19th century shopper might buy their meats from a butcher, and vegetables from various markets. They would have to travel to different sellers in their neighborhood, a time-consuming process; they might also form casual relationships with each of them. Then, as canned food became more commoditized, they were sold by grocery stores: you’d go to the grocer and tell them what you wanted, and they’d get your food from the shelves. In 1916, grocery stores became self-service: you find what you need and bring it to a human cashier with whom you’d exchange pleasantries. Starting in the 1990s, self-checkout machines meant no human interaction required. Then, delivery apps allowed you to order your groceries online: you could get all your food delivered without even leaving your house. No-contact deliveries in the pandemic meant you might not even see the delivery person. This made grocery ordering fast, easy, and without the least bit of human interaction. Some services are now testing and deploying food delivery robots.

We can repeat that kind of story for many other kinds of activities, that have, over decades, moved from time-consuming, in-person interactions to convenient, human-free apps.

Our online social interactions often have a lot of the same feel and elements of real in-person interaction. Phone calls are a great way to keep in touch, and I still treasure my regular calls with close friends. Watching social media lets you enjoy and participate in a great online conversation; I’ve learned a lot and had many meaningful interactions with colleagues and acquaintances online.

But watching social activity online is a bit like eating junk food. Junk food has the sweetness, umami, and/or saltiness that tells our animal brains that we’re consuming something nourishing. But it is not nourishing. Likewise, social technologies give us some of the elements of social relationships, without the same nourishment. Eating a bag of potato chips, or scrolling influencers on TikTok may be pleasurable, but they are unlikely to leave you feeling nourished.

One could extend the argument backward through history. When I mentioned my thesis above with some colleagues recently, one of them described books as socially isolating, and the others agreed (one described all the time her child spends reading). The industrial revolution was enormously alienating to generations of people who became mineworkers and factoryworkers, toiling in inhuman conditions for most of their waking hours. Or surely, one could say this about war technologies and surveillance—or heck, even the development of agriculture millions of years ago. If we view Pleistocene hunter-gatherer tribes as our ideal state, then every technology development has moved us away from that state, starting with the development of agriculture. But this does not seem like a productive argument.

How to Counter It

We are social creatures, evolved to live in small tribes of hunters-and-gatherers; all of our social behaviors, in some way, can be traced back to our Pleistocene ancestors. In-person interactions with neighbors and with strangers is one of our most basic needs, like food, health, and physical safety. And yet, we live in a modern world, with its complex demands and structures, and we’re not going back to our hunter-gatherer lives.

I still enjoy television, video games, social media; I daily use telephone, email, and instant messaging to keep in touch with close friends, family, and coworkers; I sometimes order food and products with delivery apps; I ride in automobiles when necessary, etc. In our modern world, each of these technologies can benefit our social relationships and other aspects of our lives. And, even if we wanted to give up these technologies, we live in a society in which doing so would be very hard. Their underlying problems are societal problems that we cannot solve alone.

However, I recommend taking stock of which relationships are valuable and/or nourishing. And, what kinds of interactions support those values? How do you feel after an evening with friends, versus an evening scrolling social media? I believe you will find that the in-person interactions are the most valuable, lead to the greatest connection and empathy. These are worth prioritizing. How can you organize your life to best support the things that matter (such as meaningful relationships) and not the things that don’t matter (sitting frustrated in traffic; scrolling social media)?

Moreover, in-person social interactions with strangers, though often fleeting, can really enhance our sense of connection with the larger society around us.

It takes conscious time and effort–and sometimes, resources—to avoid the noise and figure out what really matters.

Some readings I recommend

Derek Thompson. The Anti-Social Century. The Atlantic. 2025.

Thorough and well-researched article that makes many of these points, and more (sent to me after I posted this; thanks, Moshe Vardi).

Joe Keohane. The Power of Strangers: The Benefits of Connecting in a Suspicious World. Penguin Random House. 2022.

A surprisingly deep exploration of the value of talking to strangers, through anthropology, sociology, and psychology, and how talking to strangers is important both personally and societally.

Amy Orben. The Sisyphean Cycle of Technology Panics. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2020.

How moral panics recur over each new technology, and waste time and resources by misunderstanding the new technologies.

Peter Gray, David F. Lancy, David F. Bjorklund. Decline in Independent Activity as a Cause of Decline in Children’s Mental Well-being: Summary of the Evidence. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2023. (Alternative link.)

A compelling explanation for the rise in mental health issues.

Melvin Kranzberg. Technology and History: “Kranzberg’s Laws”. Technology and Culture. 1986.

Is technology good or bad? No.

Jane Jacobs. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Random House. 1961.

The influential and insightful account of how mid-century American urban planning fails, and how cities can function successfully.

Robert Caro. The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. Knopf. 1974.

A gripping account of (among many other things) how car transportation took over New York City, and some of the harms that resulted.

My blog post on status quo bias: peoples’ tendency to assume that new technologies and new kinds of art are bad.

My blog post on recorded music. Some pros and cons of recorded music technology.

This post was inspired, in part, by conversations with Moshe Vardi. Thanks to Steve DiVerdi and Obie Pressman for comments.