“That’s Not Art:” Art Worlds Define Art Differently

Recent conflicts over “AI” art have exposed divisions among different kinds of art and artists. In this post, I will argue that there is not one Art World, but many Art Worlds, and these different Art Worlds don’t just make art differently—they define art differently. We cannot come up with just one specific “definition of art,” because it varies so much—not just in different eras, but across different communities in the same era.

These kinds of divisions have always been around, but they’re usually hidden. Conflict, as now occurs with “AI” art, exposes these divisions.

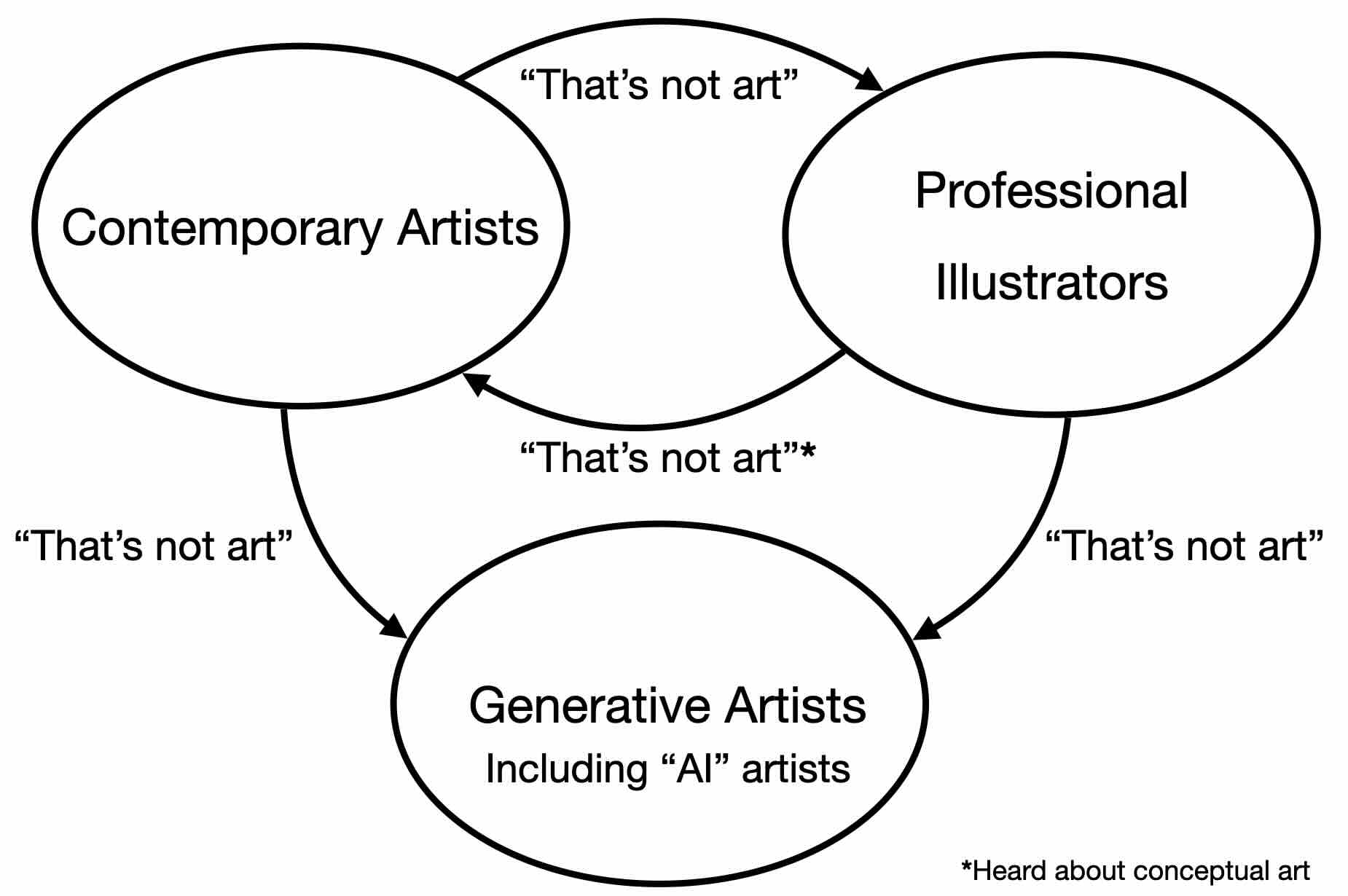

Here are some things I’ve heard from different communities about each other:

I’ll explain next the examples that make up this diagram. Then, based on these observations, I’ll propose a more general theory of how different communities define art, and so these different communities talk past each other.

Sociologists like Pierre Bourdieu and Harold Becker have written extensively about social creation of art, but not (to my limited knowledge) about definitions of art themselves being community constructions, and Larry Shiner’s analysis cuts across historical periods rather than today’s communities.

Several times in the past few years, non-artist friends or colleagues asked me “What do artists think about AI?” It should become clear from this discussion why there’s no simple answer to the question.

(As usual, I put “AI” in quotes because it’s not human-like intelligence, it’s just software.)

The view from the Contemporary Art World

Until recently, the Contemporary Art World has paid little attention to generative art, and its latest incarnation, “AI” art. When The Machine Made Art details this decades-long history of disinterest and antipathy toward any sort of computer-based art.

When computers do appear in Contemporary Art, it’s art by artists who are from that world, like Harold Cohen, Trevor Paglen and Jason Salavon, using the computers to do Contemporary Art things.

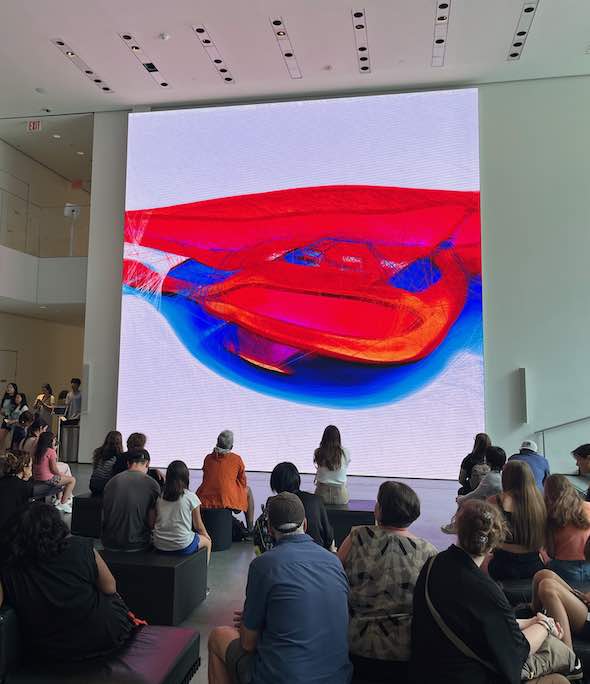

So Refik Anadol’s “Unsupervised” display wall at the MOMA provides an instructive example. This work combines generative networks trained on MOMA’s artworks, fluid simulation, and futuristic visualizations and has drawn crowds. At the same time, the antibodies of the contemporary art world attacked it. Ben Davis called it a “lava lamp,” Jerry Saltz dismissed it as a mind-numbing mediocrity.

I enjoyed the work, and I was glad to see lots of other people enjoying it. I didn’t find it particlarly unique or intellectually interesting; I sympathize with criticisms of the work as being intellectually shallow. (It wasn’t the dullest thing in the MOMA either.)

In order to understand the criticism, it’s important to understand that the Contemporary Art World emphasizes ideas first. Multiple artists have told me that “AI” art is not art. When I asked for clarification one told me that “Visual works of art are not images, but ideas expressed through images.” An image without an interesting idea behind it is not art. But, moreover, to be interesting, it should speak to ideas in that community. This is why the Contemporary Art World is often described as a “conversation:” new art works speak to and respond to previous artworks.

So, art critics critize according to the values of the contemporary art world. They’re focused on the ideas behind the work, and the dangers of high-art institutions being driven by profit. In contrast, for a lot of people, if the work is dazzling, beautiful, and/or impressive, then those concerns about concepts and profits would be secondary, or even irrelevant.

Hence, by Contemporary Art standards, most generative art is not art, most “AI” art is not art. And, obviously, professional illustration and design are not art.

Membership in a community plays a key role in who learns the rules of the game and gets acceptance.

Refik Anadol is an outsider to the Contemporary Art World, e.g., he came from a media arts arts school, not a prestigious contemporary art school. When I visited his studio in 2019, he described the movie “Blade Runner” as his primary artistic inspiration, with its notion of robots “dreaming.” His slide presentation and animations used flickery, science-fictiony text dashboards, as now appear in “Unsupervised.” He described his work in sci-fi talk of robots dreaming. So he has neither the background, the subject matter, nor the language of the Contemporary Art World. He doesn’t talk like them, he doesn’t come from their background, he doesn’t talk about the things they care about. And, when he responded to Saltz’ criticism, he argued that Saltz needs to better understand the “AI” art medium, rather than trying to situate his work in the Contemporary Art world.

Two notions of art, talking past each other.

Now that Anadol’s work has been shown and collected by the MOMA, and art critics engage it seriously, I suppose it’s been upgraded from “not art” to “bad art.”

In contrast, consider Harold Cohen. He wrote code to make pictures beginning in the 1960s, with a decades-spanning career and work collected in major museums in galleries. He wrote and spoke extensively about whether the computer could itself be the artist. But he wasn’t considered a computer artist or “AI” artist: he was, first and foremost, a contemporary artist who happened to use computers. He was accepted and collected in the mainstream artworld because he had the pedigree (a prestigious fine-art education), the right galleries, and he spoke the right language.

The Contemporary Art World does admit outsiders, e.g., “outsider art,” or shows from the MOMA on video games and fashion. But they’re not dropping the barriers; they’re just admitting a lucky few to the club, sponsored and shepherded by current members like gallerists and curators. The MOMA, in a sense, made a tentative move by bringing “Unsupervised” into its walls—and they could have walked it back.

So I have found it fascinating over the past few years to see some “AI” artists making making slow inroads into the Contemporary Art World, e.g., the recent show at Unit London curated by Luba Elliott.

(Another instructive cross-art-culture example is TikTok artist Devon Rodriguez’s attack on Ben Davis, after a critical art-world review. Davis’ incisive analysis is worth reading.)

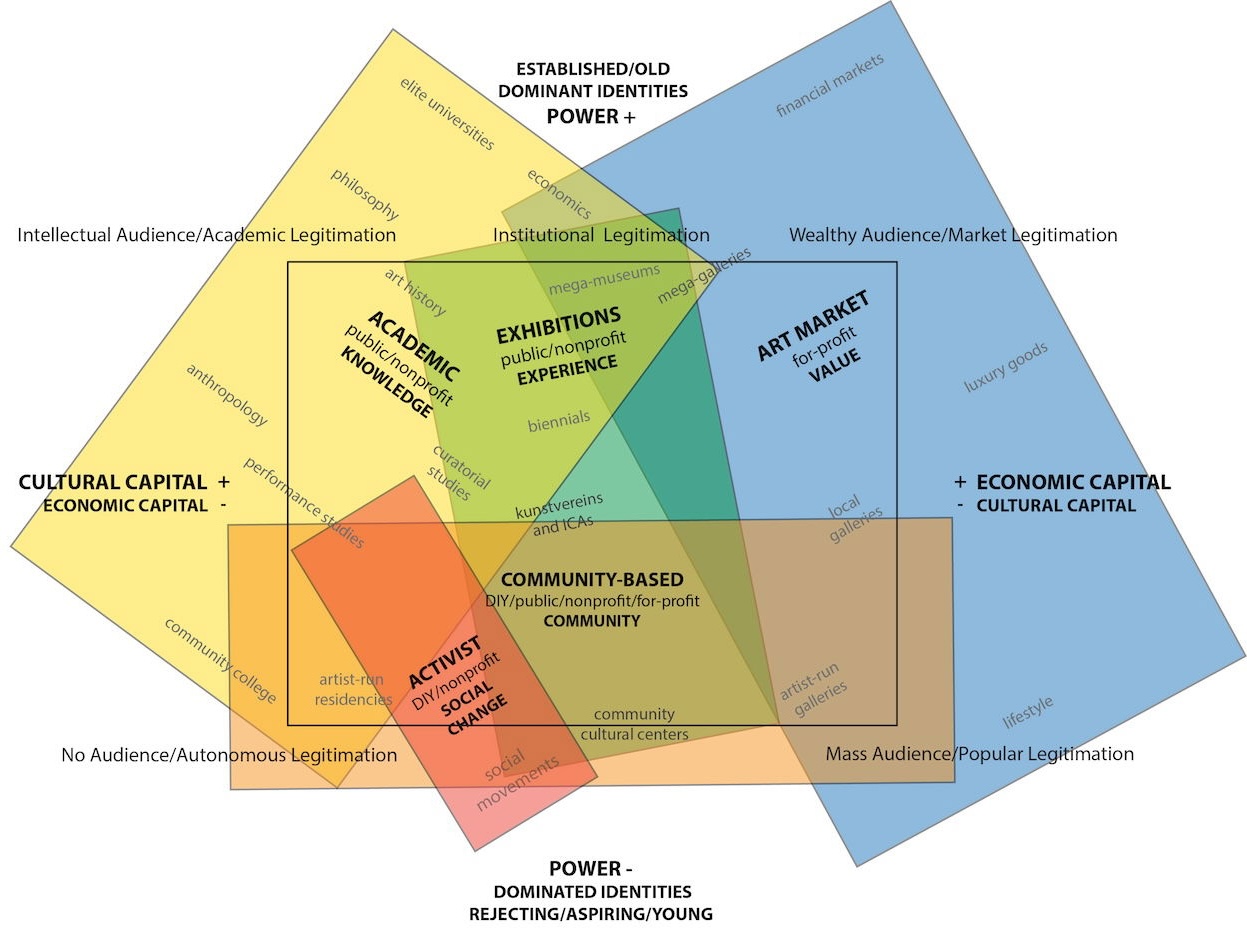

So far, I’ve oversimplified: the Contemporary Art World isn’t just one community, but comprises many subgroups. For example, there’s a sharp divide between Biennial Art and Art Market Art. In Ben Davis’ words, “The biennial circuit is fueled by its own system of demand, hype, and trends. It is a parallel universe with its own rules, hierarchies, challenges, and, crucially, its own economy.” These worlds rarely intersect. Lev Manovich additionally points out that many of the artists most successful at showing these biennales come from just a handful of art schools: pedigree and social connections matter. However, even though the Biennial Art World and Art Market World have very distinct values in art, they would each recognize each other as making Art, whether or not they respect it.

Update (Aug 2025): Here’s an amazing diagram of different subcultures of the “Art World”, from an essay by Andrea Fraser. See the essay for more about the figure and the different art worlds it depicts.

For more about the contemporary art world as its own community, such as the importance of ambiguity, see my previous blog post.

The view from professional illustration and art

Text-to-image’s appearance last year, like any new artistic technology, encouraged lots of new artistic exploration; such experimentation is sometimes interesting, often tedious, and/or disposable. And, like any new technology these days, there’s also a boatload of hype.

In the past year, many professional artists and illustrators have lobbied hard against “AI” art, in social media, public writing, and lawsuits. They argue that this technology harms their careers, and make ethical arguments about training data. But some of them extend the argument to definitional grounds: they say this is not art.

Real art comes from an artist’s hand, they say; it’s expressive and personal. It has heart and soul, all things missing from “AI” art. It cheapens and degrades real art, replacing it with mechanized trash: fake art. People making pictures with these tools are not artists, technology hype has deluded them into thinking that pressing a button makes them artists, by a simulation of creativity that is not real creativity (that the professionals are experts in).

In short, these professional artists define art in terms of handmade work and direct authoring, as in physical or digital painting, or writing the words of a novel yourself. They define it in terms of the things that are currently important to success in their careers.

But, some respond, doesn’t this exclude the entire history of conceptual art—and some of the most important works we learn about in art history and see in, say, the MOMA?

I’ve seen more than one case, both publicly and privately where illustrators deny that conceptual art is art all. In one private discussion, I’ve seen one vocal illustrator explicitly say that they don’t consider Duchamp’s fountain to be art at all.

Sure, professional artists might love and appreciate many recent works in the MOMA. But the intellectual gulf is vast. Since Marcel Duchamp and John Baldessari, the Contemporary Art world views the artwork as the expression of a concept or idea; technical skill and artistic expression are not necessary for art. For professional artists, skill and expressivity are central to art, and the concept is optional.

I can relate to this view. Back when I started to really enjoy my college art classes—and hadn’t even heard of computer art, per se—I once told my father that photography was not really art. This was, perhaps, a poor choice, as I had forgotten that he once ran a photo studio and that my uncle’s whole career is dealing vintage photography. (My father was very patient with me.) At the time, I was immersed in the feeling of creativity and expressivity of painting and drawing, and hadn’t paid much attention to photography as art, so of course I had no idea of the creative aspects of photography. (And this was before I’d even heard of computer art, per se.)

When you’re immersed in a way of working, participating in a community formed around that way of working, and getting rewards and benefits for that way of working, it can become not just a way of working, but a belief system. The same is true for any art community, whether contemporary art, illustration, and many, many others.

There’s another, even smaller, artist world, roughly the “atelier” world, of painters who reject any sort of technology in their art. For them, even using a digital painting program isn’t really art. For them, you have to be using physical media.

The view from generative art and “AI” art

People have been making art with computers for as long as we’ve had computers that can make pictures, about 60 years. Generative artists have been writing their own code to make art for this whole time. Neural “AI” art has been around for about a decade. But, as detailed in When The Machine Made Art, generative artists have always operated outside of the mainstream, rarely finding acceptance in the art institutions.

At the risk of sounding like an insufferable hipster, I enjoyed “AI” art far more before the current text-to-image boom, back when the “AI” artists were largely writing their own code and even curating their own datasets. Online communities emerged around “AI” art; I learned about some of my favorite artists, and made many connections on Twitter and other networks. These online communities became especially vibrant during the pandemic lockdowns. Some value systems seemed to emerge in this time, in favor of sharing information and data, and writing one’s own code. Debates and conflicts occurred when artists used others’ systems to sell artwork (most prominently, the Christie’s auction by Obvious, but there were other examples), as the community felt its way toward shared values around these things. It didn’t last long before text-to-image blew it all up.

I think text-to-image generation is a fad, but it sucks all the air out of the room in the “AI art” discussions.

The view from nowhere in particular

If you work in a focused art community, whether as an artist, critic, gallerist, or other role, or just follow it as an ardent fan, then you may absorb that community’s beliefs, values, and definitions of art.

Most people, though, aren’t immersed in one of these communities. Everyone has their own preferences and opinions of art, and what they like and what they hate, and some opinions about what defines art, but rarely sharp definitional barriers (“that’s not art”), except sometimes for esoteric conceptual art.

See this previous blog post a survey of some commonly-used definitions of art, although I’d now write it differently given the ideas in this post.

These definitional gulfs are invisible and vast

So often, people seem to treat the words “art” and “artist” as if they each mean just one thing, like when when friends and colleagues have asked me “What do artists think of AI?” It should be clear from the essay so far that there’s no simple answer to this question.

But it’s not just that they have different definitions of art. Within these established art communities, not only do they define “art” differently, they rarely acknowledge or recognize that other definitions exist.

In my contemporary art readings, the authors never qualify what they mean by “art.” They assume that art only means the fine art/contemporary art world, and never say “I’m not talking about music or cinema or comic books or illustration.”

And it’s not just in specialized theory texts. For example, Jerry Saltz’ How to Be An Artist, a New York Times bestseller, includes many bits of wisdom. But he’s clearly really giving advice on how to be a contemporary artist, for example, offering career advice on galleries and networking that would be largely irrelevant to someone setting out to be a musician or filmmaker or cartoonist. As with most contemporary art books and articles I’ve read, it’s as if “art” is synonymous with “contemporary art.” There is no other kind of “art.”

So, when these communities come into conflict, discussing, for example, how “AI” might affect “art,” it unsurprising that people are talking past each other. Each has opposing definitions of “art,” and none ever seem to acknowledge this.

We see online conversations where professional artists say that “AI” art can’t be art because it’s pushbutton copying and doesn’t have the artists’ hand, and others responding “what about photography, readymades, and photomontage art?” and these debates seem doomed to never find common ground.

Art Worlds Define Art

Based on the observations, I here propose a theory that different art worlds that each define art separately.

In his 1964 essay, philosopher and art critic Arthur Danto introduced the term “Art World” to define the community that together creates and defines art. This has become one of the standard definitions of art, that it is defined by The Art World. Since then, philosophers like George Dickie and Jerrold Levinson have refined the idea, whereas sociologist Harold Becker used the phrase “Art Worlds” to discuss how different communities create art in different ways.

But, to my knowledge, none of the theories allow for distinct, incompatible definitions of art to coexist, int the ways I’ve described above.

In summary:

- Each art community has its own preferences for what it values in art.

- These values reflect and reinforce the community’s goals and reward systems.

- Often, these communities define the words “art” and “artist” according to those values.

- People who are more invested in specific communities are more likely to internalize the values and definitions of that community.

- For people invested in a community:

- When discussing “art,” it is unnecessary to clarify what kind of “art” you mean, because no other definition of art exists than your own.

- If it doesn’t fit the community’s values, it’s not art, and it does not deserve consideration or respect. It may even be a threat to “real” art.

- When people with conflicting values and definitions for art interact, confusion and conflict ensue, especially on highly-charged issues.

Art Worlds are not constant, they can appear, change, split, merge and/or disappear. In a previous blog post, I wrote about how different eras in human history had radically different conceptions of art—most of our modern concepts of art would be totally unrecognizable to, say, Leonardo da Vinci. In each era, the values and definitions of art went together. In that post, I treated each era as its own “community.” Now I’m just looking at some of the different communities of our own era.

As I’ve discussed, the Contemporary Art World has many of its own factions and divisions, such as Biennale Art and Art Market Art, and each of these will have their own divisions. They tend to have distinct values (e.g., Art Market is commercial, Biennale is anti-commercial), but their communities mingle and recognize each others’ art as art.

Other communities form around other kinds of art, whether visual effects, fan art, atelier art (a very traditional community which doesn’t even recognize photography as art), hip-hop, and so many others.

Anywhere you find a community of artists, you may find an Art World.

Thanks to Itay Goetz, Laura Herman and Craig Reynolds.