Learning from Painting, Part 4: Time and Speed

We sometimes think that technically-impressive, labor-intensive artworks are better. But working fast doesn’t just make you more efficient: with practice, it can bring life to your work. Some of my favorite pictures were the fastest.

This is the fourth part of a series of blog posts about my recent experience in digital painting and drawing. Click here for the first part.

Time Constraints

By far the biggest determinant of my style was time pressure, internal and external. Sometimes I only had a few minutes to spare to draw a picture. But even if I had all the time in the world, I still felt some time pressure because of the opportunity cost: some other picture I could be drawing instead, or some other activity I could be doing. At some point, I will simply get tired of the focused effort, or hungry, or bored with this activity, or distracted by important emails. The pressure to work fast itself—or the determination to work slowly—affects all of the choices that determine style.

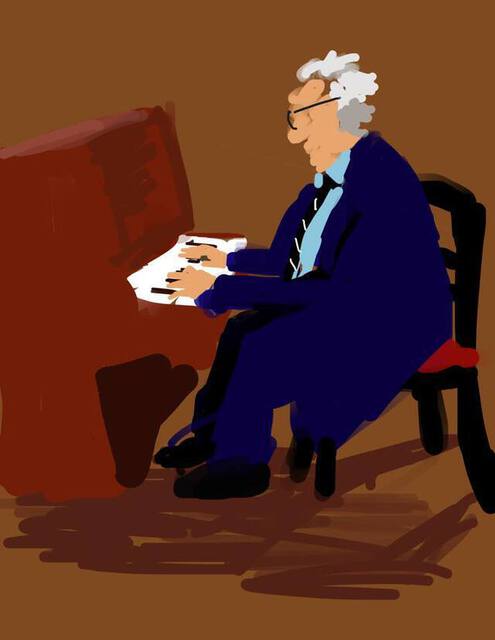

In one extreme case, I was taken with this piano player in a restaurant; since I didn’t have my iPad with me, I quickly installed a drawing app on my phone and sketched this my finger:

which is one of my favorite drawings. Maybe the beer helped a little too.

Twice, I’ve made a conscious decision to invest as much time as necessary for a detailed, complex painting. The first time was this painting, for which I made a rough sketch on-site, and spent many hours refining it later based on reference photos:

Here’s the other picture to which I devoted many hours. These don’t feel like they’re worth the effort.

The effect of time constraints is more than just determining how much detail can be drawn. Every single choice in the process seems loaded with opportunity cost. If I decide to draw straightahead without an initial sketch, I might get results faster, but I might be unsatisfied with the composition. So I can sketch the composition, but this takes time away from drawing the details. Besides, I am almost always excited about drawing the details and bored with the idea of sketching. I want to get to the fun stuff quickly. Time pressure also affects how likely I am to give up on the drawing if I’m not optimistic it’s going to turn out well.

When it works, I look back with some amazement: how did the piano player’s face come out so good? I don’t think was conscious of every stroke, every gesture.

Here’s an example of fast sketching without planning; the shapes are a bit lopsided, but I could work fast and save time.

“First Thought, Best Thought”

I’ve always been attracted to making loose, expressive drawings, feeling that a skillful drawing made quickly can be more engaging than one that is labored and deliberate. On the other hand, in our society I think there is a general belief that a more technically skillful and impressive image is a better one, a prejudice I sometimes share. Of course, both have value. But I think that expressive drawing is underappreciated skill.

This notion that quick works can be more expressive isn’t just about efficiency or impatience. In the liner notes to Miles Davis’ famous album Kind of Blue, the pianist Bill Evans describes how nearly all of the album was recorded with almost no rehearsal, and only minimal instructions given to the players. He makes an analogy to Zen Buddhist sumi-e painting, where loose brush strokes are drawn in a single, deliberate process by a painting master, without corrections or modifications possible. The Buddhist teacher Chogyam Trungpa used the phrase “First Thought, Best Thought” to describe how an initial moment of observation can be aware and unclouded; an initial expression can be fresh and original. This in turn influenced Beat poets like Allen Ginsberg, who, in the same era as Kind of Blue, also strove for spontaneous expression.

In each of these cases, an experienced artist can draw something very quickly that is quite expressive, and the expressivity and style comes from both the skill and experience of the artist, together with the constraint for speed, no corrections, no erasures, no second-guessing.

Here’s another sketch from my cellphone, of a centerpiece at a restaurant:

Mistakes, Luck, Experience

Of course, I’m describing the times when it all seems to work out; lots of sketchy attempts don’t look very good. There seems to be some luck involved. Here’s one I don’t think of as being so successful, though I guess I liked it enough to share. Here’s a similar one that I liked much more. To quote Linus Pauling, the best way to have a good idea is to have lots of ideas.

When you work fast, you can make mistakes. And sometimes those mistakes become your favorite part of the picture, like the way this plant accidentally went off the edges of the frame, or ,in this recent drawing the unrealistic way the paint from the table mixes with the black window frame behind it. The mistakes are part of what give a drawing “life,” especially in contrast to machine-perfect drafting.

Practice and experience seems to make it easier to make good mistakes. Maybe experience makes it easier to figure out which mistakes to keep.

Drawing with my finger on the phone—as with the piano player and centerpiece above—feels really clumsy, like trying to write a postcard with a floor mop. That clumsiness can be a virtue, for example, forcing me to work in a loose way that does more than less. It’s a good exercise, and something you can do almost anywhere. Very few of my phone drawings look good to me, though.

I’ve also found I can’t repeat “success.” In my college painting program, I distictly remember painting the red roofs of houses mixed among trees on a hillside. I liked the painting a lot, so, after I sent that postcard to some friend or family member, I tried painting it again on another postcard, and I thought the second try completely fell flat, dead, lifeless. Whatever “successful” means, successful painting is ephemeral and elusive. Once you’ve done something you like and reflected upon it, it’s time to move on to a new challenge.

Lynda Barry observes that her untrained students’ drawings have a particular liveliness. As you gain experience, how do you keep what Zen Buddhists call “beginner’s mind”?

In retrospect, I’ve been continually attempt paintings at the edge of my skill, trying things that are just a bit too difficult. It seems that interesting things happen when you try to do something you don’t know how to do, or whether you’re even capable of it.

“Your Shortcuts Become Your Style”

“Expressive” and “detailed” don’t have to be exclusive. I found that my practice at fast sketching made my slower drawings better, and this fluidity could help even with detailed compositions:

In a recent talk, generative artist Zach Lieberman said something like “Your shortcuts become your style.” He was talking about the use of programming shortcuts in generative art. But the statement applies just as well to my painting experience: the shortcuts I took to get through the sketch faster affect the final result.

Learning to sketch quickly helped me block out and plan more detailed compositions better, compositions could be both loose and detailed. Here’s a painting from March 2020, much later than the other paintings here:

The next post in this series is here

The paintings on this page were made between August and December 2019, and March 2020.