Visual Illusions Explainable by the Limitations of Peripheral Vision

What happens when you look at a picture? Your eyes move over the picture, to take in different parts of it. In each eye fixation on a picture, you get a sense of part of a picture, and piece those different parts together in some way.

Most of the time, we don’t really think about these eye movements and the role they play. But something complicated is happening in the way we connect these fixations.

This blog post describes a set of visual illusions (a.k.a. optical illusions) that reveal these complications.

All of these examples give a very different impression of a part of the picture when you like right at it, versus when you look to the side. This creates an illusory sense that the picture changes whenever you move your eyes from one part to another.

It’s very weird for part of a still image to look different depending on where you fixate.

I hypothesize that these phenomena can be explained by peripheral visual encodings, which I’ll explain below. These illusions demonstrate the importance of peripheral vision in perceiving pictures, and what happens when peripheral vision get “confused,” and how it does.

My previous blog post discussed how these same concepts around peripheral vision explain real-world illusions of awareness.

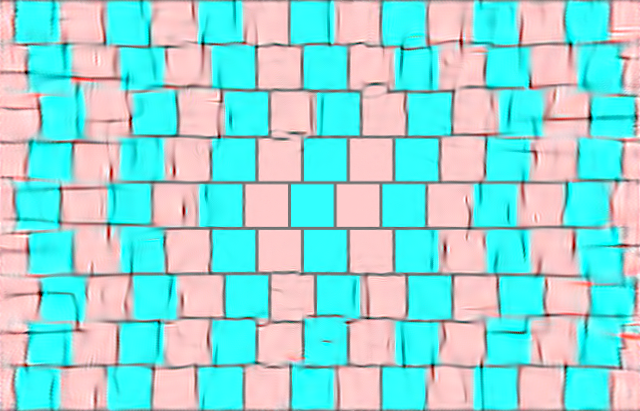

The Cafe Wall Illusion

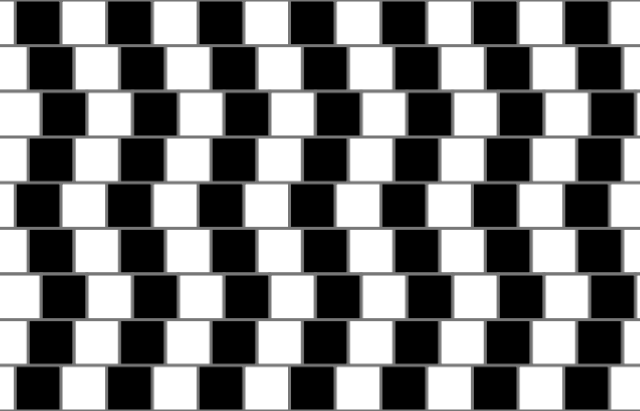

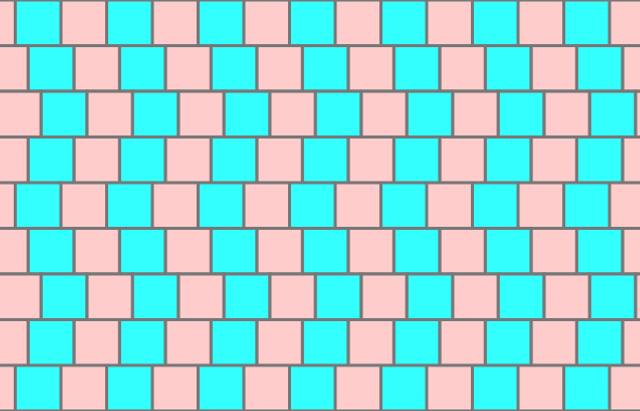

Here’s a pattern in which the lines look curved and tilted:

Yet, if you search over the image, you won’t find any individual lines that are curved or tilted.

This is called the Café Wall illusion, and the first version of it was described by 19th-Century psychologist. It now gets its name from the pattern of tiles on the wall of a cafe.

Here’s the same picture, but with lower-contrast tiles, to demonstrate that the lines are actually straight:

Here’s the key thing to notice, when looking at the cafe wall illusion. When you fixate your eyes on any specific part of the picture, the lines look straight and axis-aligned (either horizontal or vertical). But, off to the side, the lines look curving and tilting. Then, when you move your eyes, everything seems to shift: now the new lines you’re fixating on are straight and axis-aligned, and the part you were just looking at is curved and tilting. It’s as if the picture happened to change exactly when you moved your eyes. This kind of visual contradiction doesn’t happen in normal pictures,

The Entangled Illusion and Eye Movements

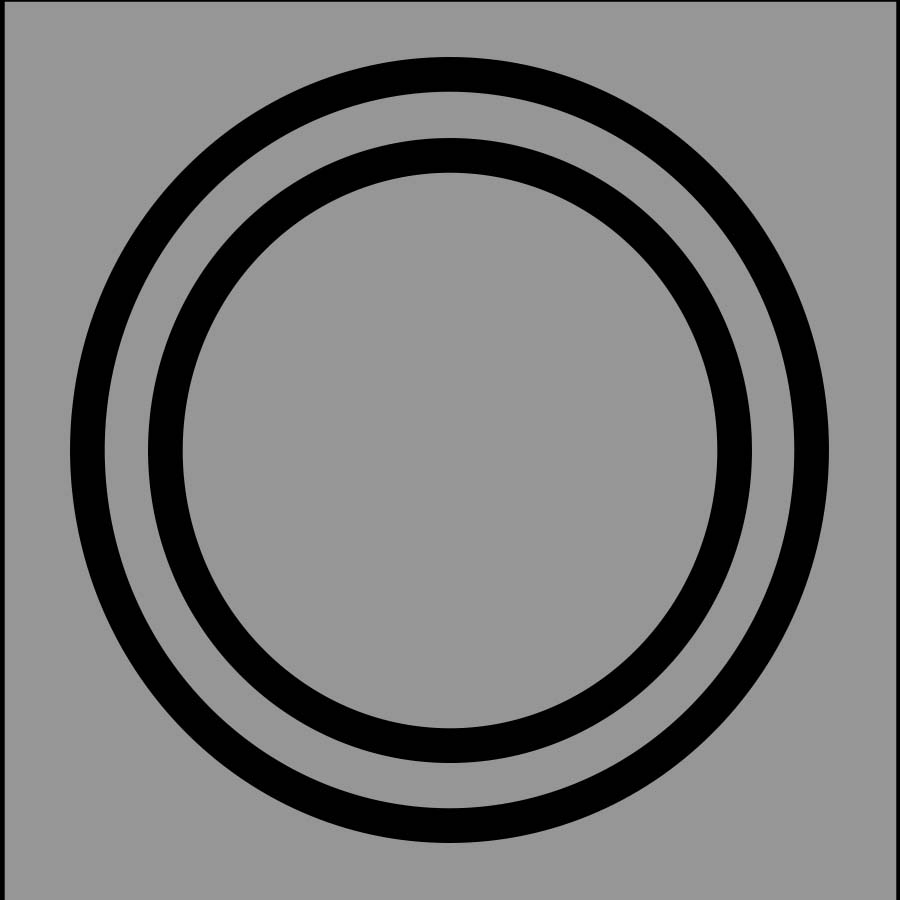

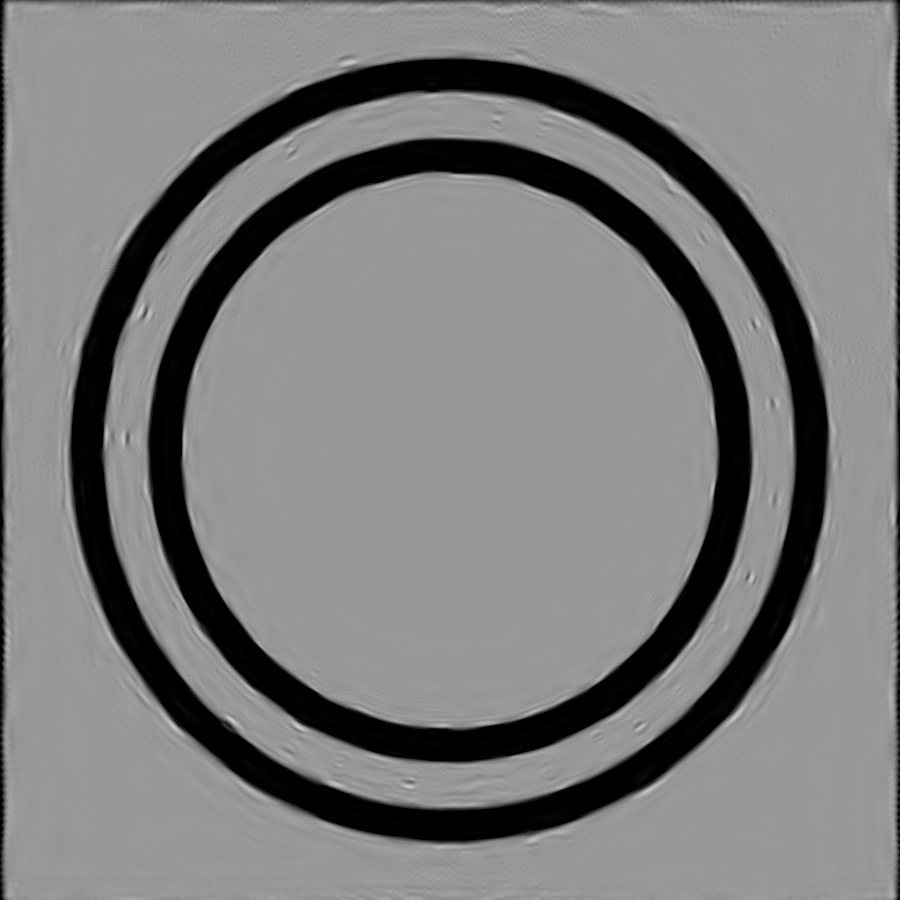

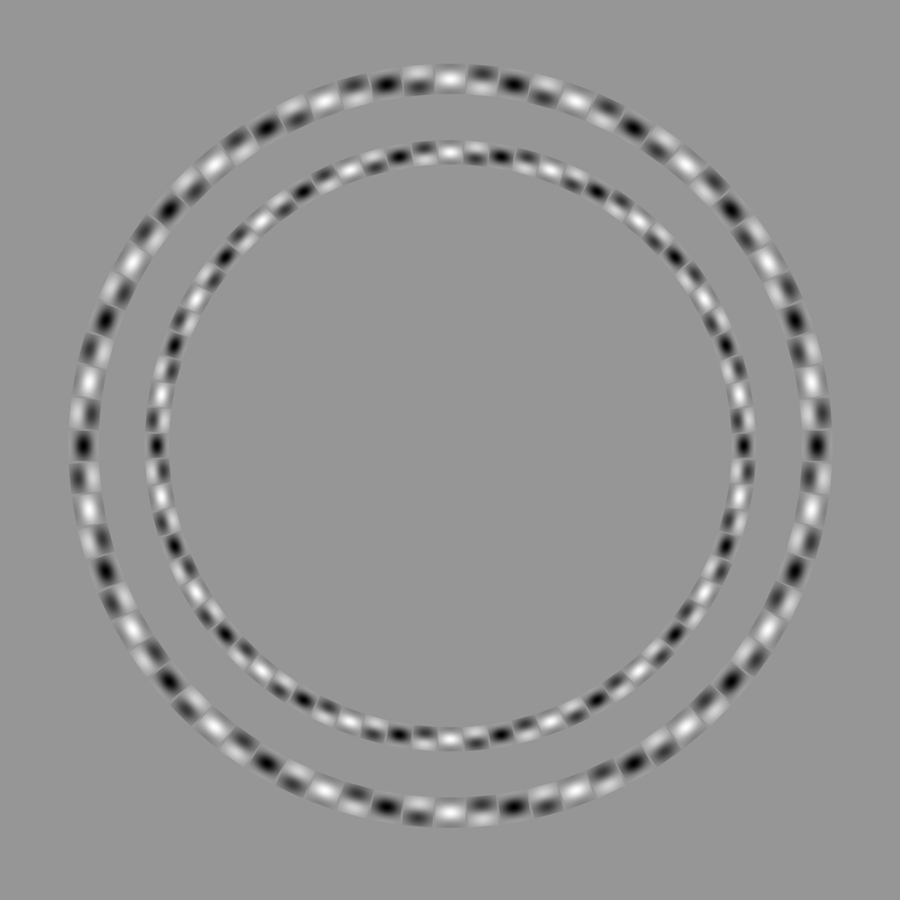

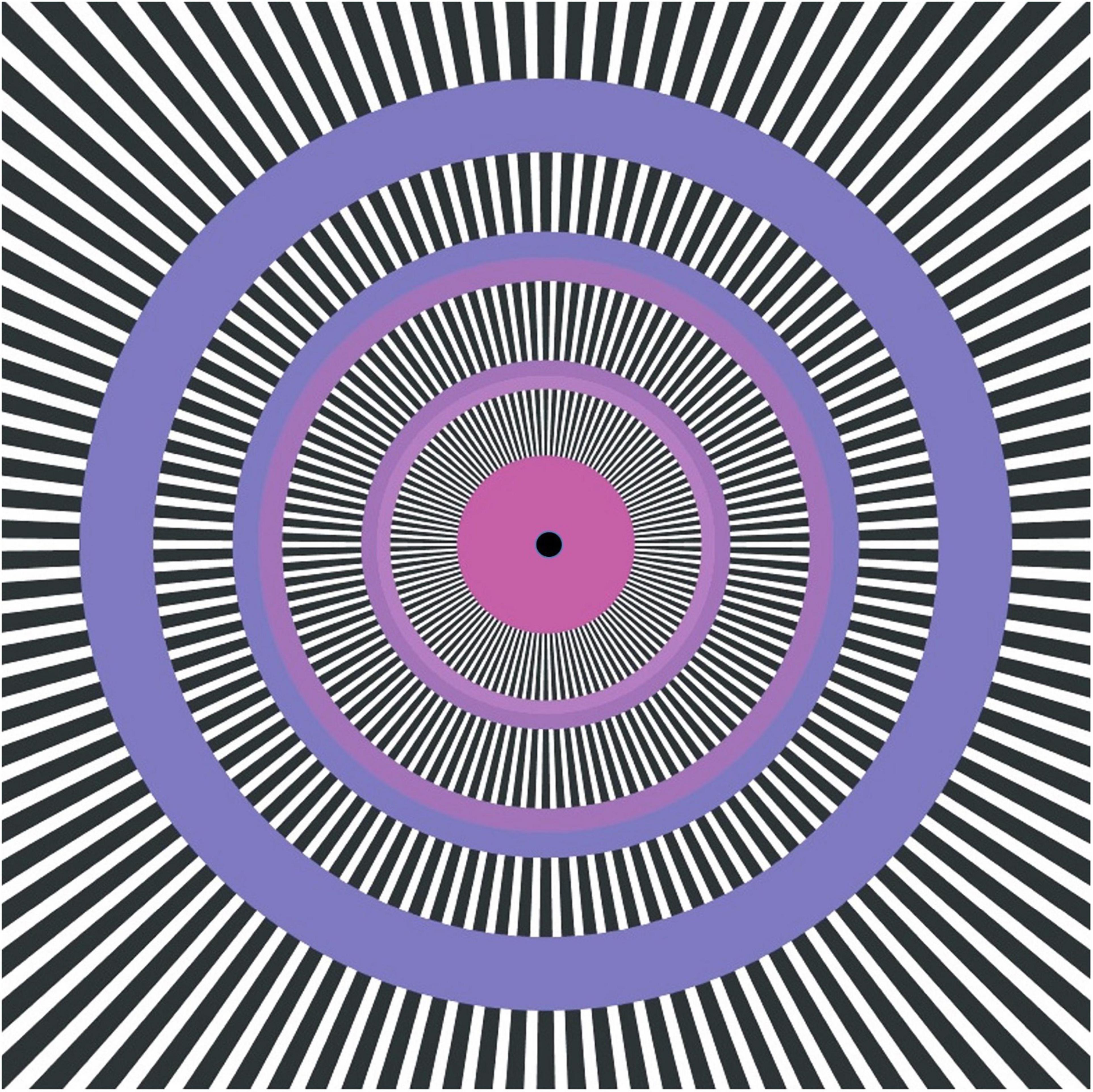

Here are two concentric rings that do not look like concentric rings:

Somehow they seem connected, yet, in each point you fixate on, they appear as two separate rings. You can trace your eyes or finger around the space between the circles to confirm it.

Here, the difference between the parts you fixate, and the parts off to the side, is substantial, almost like they’re different pictures. There are two separate rings where you fixate, but they seem connected somehow off to the side. But, if you move your eyes, the roles shift.

What’s going on: peripheral visual encoding

Although we see a wide field-of-view from each eye, we see fine detail only in a narrow range. For example, fixate your eye on any word and see how many other words nearby that you can read. Not very many. If you hold out your hand at arms’ length, then the region where you get fine detail is, roughly, the size of your thumb (or maybe the width of five fingers, it doesn’t matter), which is a tiny fraction all the things you see.

Everything outside that thumb-width of whatever you’re looking at is called peripheral vision. Peripheral vision doesn’t give as much detail as the things we look right at. For this reason, scientists often talk about it as though it’s just blurry vision. But it’s more complicated than that.

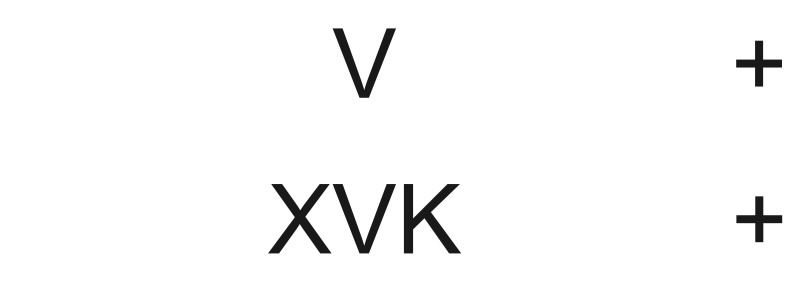

For example, if you stare at the top +, then it should be easy to recognize the V to the left. However, if you stare at the bottom +, then the V is unrecognizable, even though it’s the same size and distance from the +.

This is because of the peripheral visual encoding: the brain doesn’t just store a blurry picture of the light in peripheral vision, it summarizes it with statistical measurements. At this statistical encoding can mix things together, losing information about which letter is which when there are multiple letters.

I hypothesize that for the illusions on this page, the fact that things look different when viewed directly, versus in peripheral vision, suggests that peripheral visual encodings cause the illusions.

Spatial metamer visualizations

It’s not easy to understand or visualize peripheral visual encodings. It seems that the brain is converting light measurements into a high-dimensional feature space of summary statistics, and these do not have easy visual interpretations.

Vision scientists visualize these encodings with spatial metamers: pictures that have visually equivalent statistics to a given image, for a given fixation. That is, you pick an eye gaze location in a picture, and a metamer can be generated that jumbles up the image in a way that is not noticable when fixating on that location. These metamers illustrate that peripheral vision isn’t just blurry vision.

Here is an example:

The middle and rightmost pictures are two spatial metamers of the left image. As long as the pictures are displayed large enough on your screen, then looking at the middle or rightmost picture should look the same as looking at the left picture, but only when looking at the center.

In their edges, the metamers look jumbled up. The peripheral visual encoding, formed of statistical summaries, doesn’t notice the jumble.

This video provides a compelling demonstration, at about 10 seconds in:

If you follow the red dot closely, you shouldn’t notice the picture changing at all. If you look away from the red dot, you can easily see the background change.

Metamer visualization of the illusions

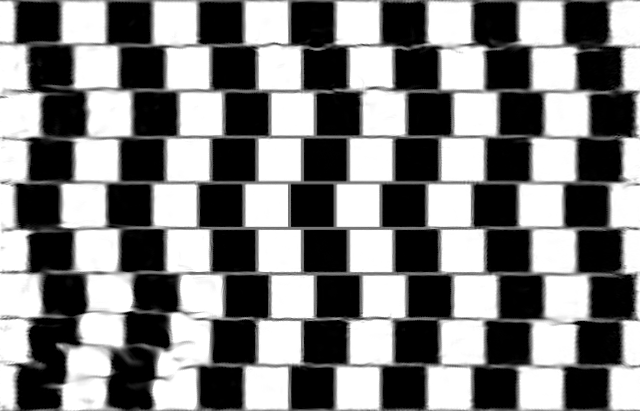

Here’s a metamer of the low-contrast cafe wall (generated using code from Brown et al.):

In principle, this picture should look the same as the original if you fixate on its center; although it doesn’t work for me, this might be a failure case of the algorithm, or maybe I didn’t blow it up large enough. Even so, the key thing to notice here is that the jumbled-up picture still has a lot of horizontal and vertical lines. It seems like preserving important peripheral statistics of this picture involves using horizontal and vertical lines. Even where there’s some waviness, there’s no clear “tilt” or orientation.

Here’s a metamer of the original cafe wall illusion (with color removed):

Now, the image periphery includes more-tilted lines; it’s most visible in the lower-left. In the upper-right, there seem to be more angled lines. So this effect is subtle, but I seems to support the hypothesis that the cafe wall creates peripheral encodings corresponding to tilted statistcs. While I don’t think these metamers prove anything, I think they support the interpretations I’m proposing.

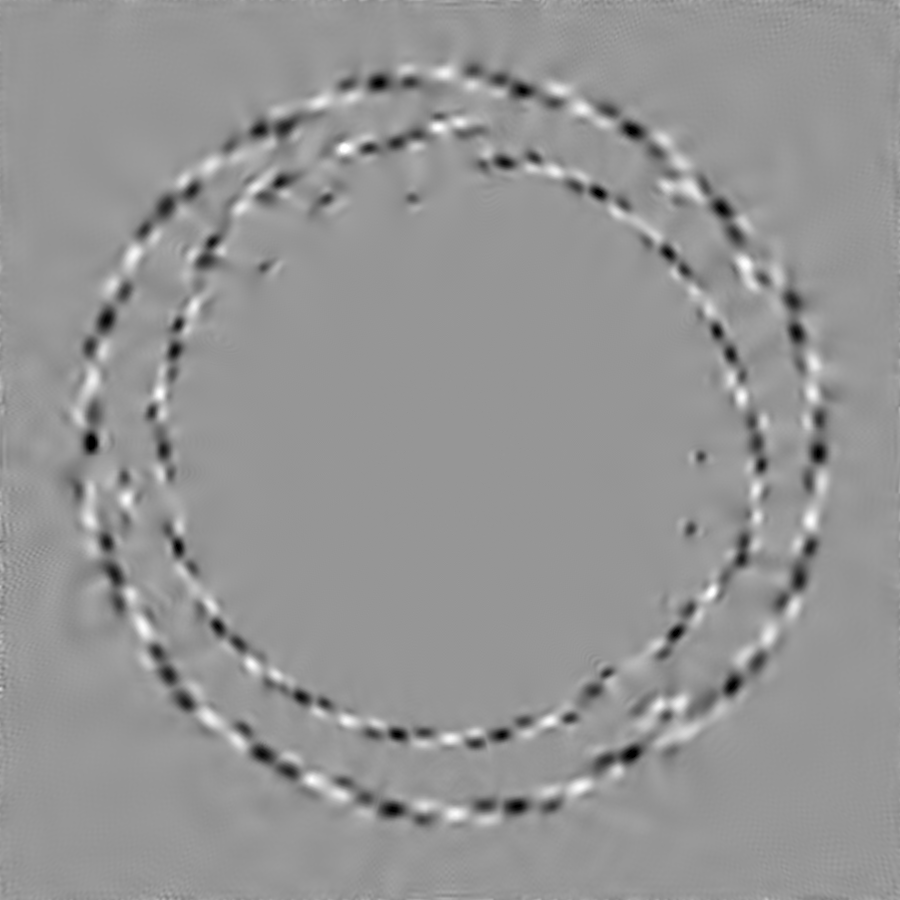

Here’s a metamer of the entanglement illusion:

Notice how the curves get broken up. But if we make the rings solid:

Then the metamer is solid as well:

More Tilt Illusions

Similar effects occur in many other illusions. In each case, the illusory effect appears in peripheral vision, but not in fixations. The two seem to have contradictory appearances, and so the picture’s appearance changes as you move your eyes.

A heuristic I follow here is: if the visual impression you get fixating on a point contradicts the impression when the point is viewed from the side, then the illusion might be caused by peripheral encodings. In the Cafe Wall illusion, points look rectinilinear when viewed directly and angled in peripheral vision.

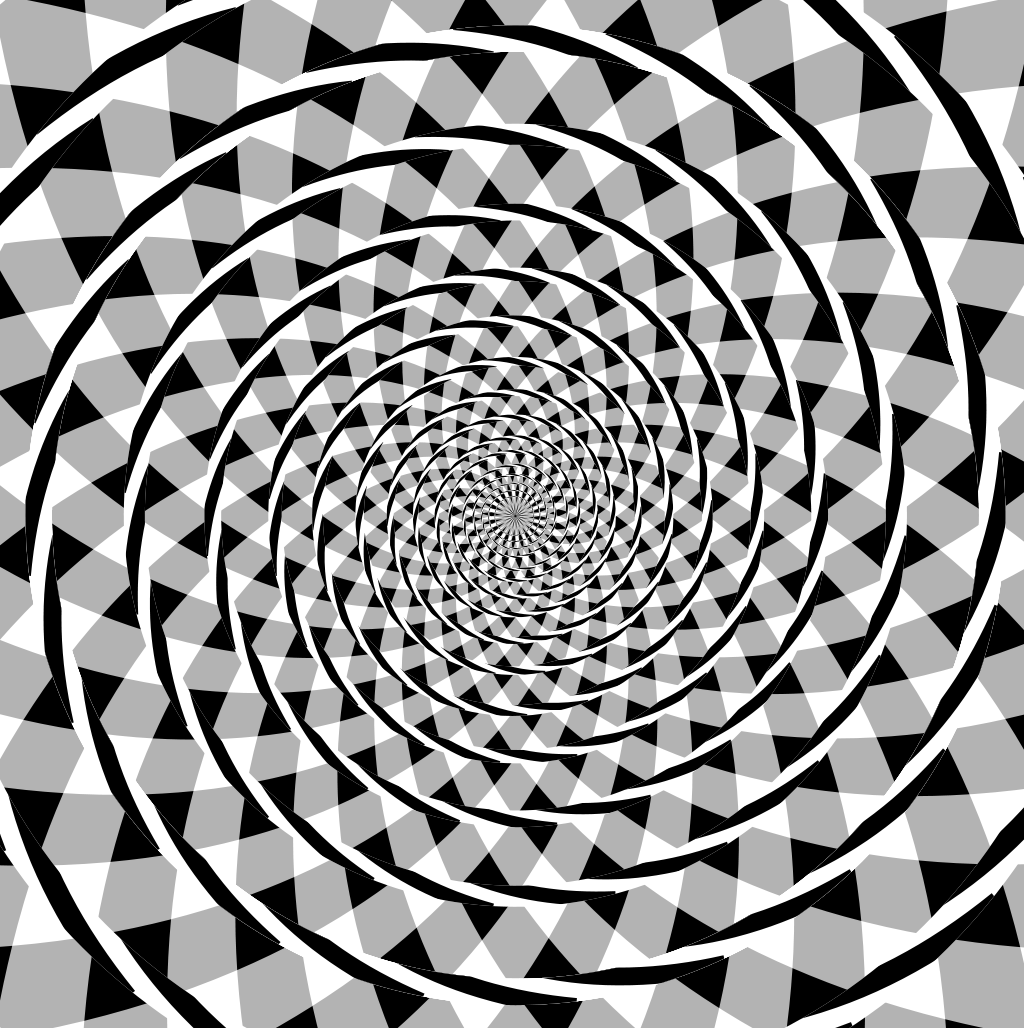

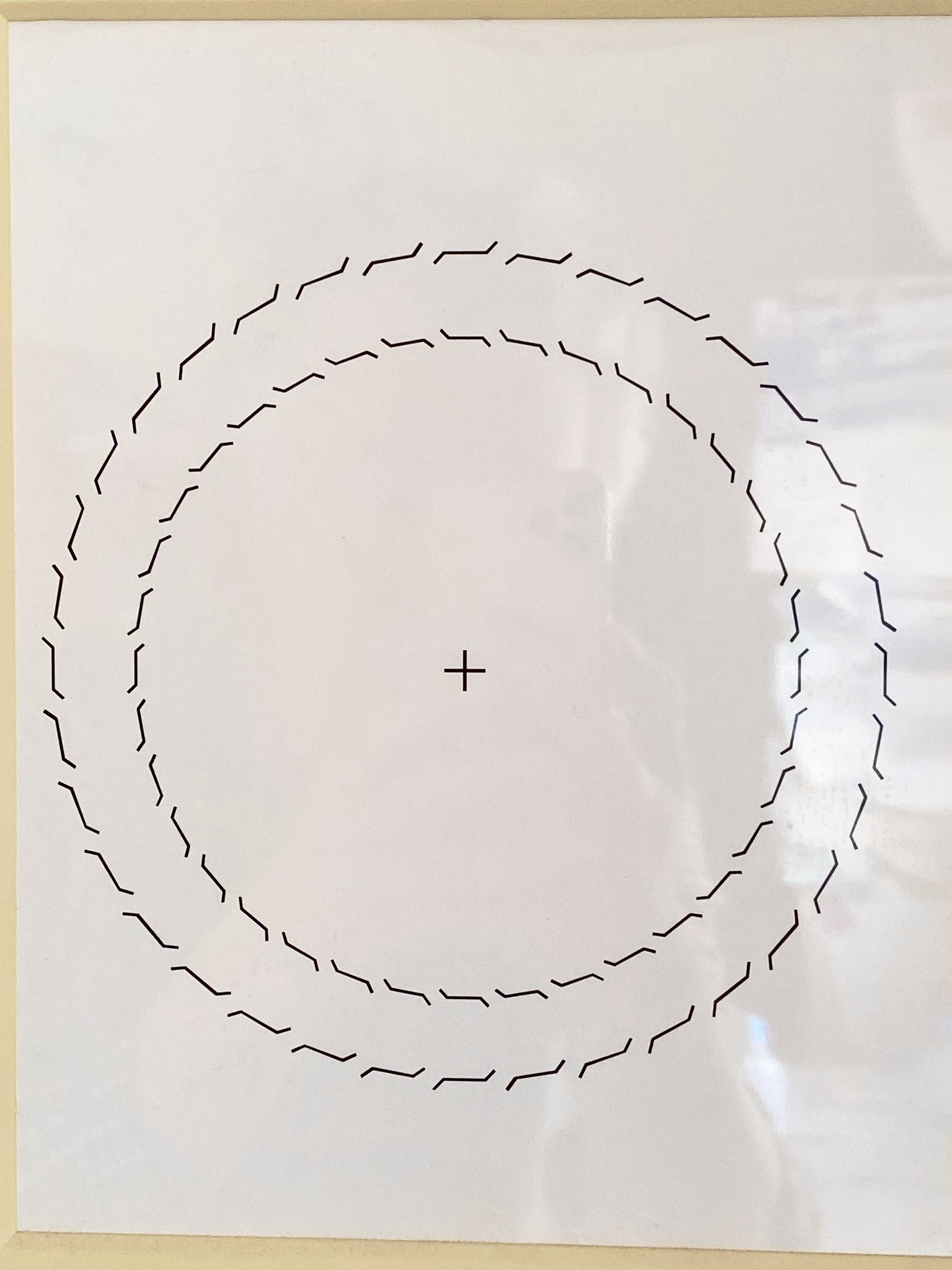

Fraser spiral. The Fraser Spiral, created by a British psychologist in 1908, shows a more complex version of the same phtenomenon:

This, too, consists of concentric circles, but it looks like a spiral.

In each case, any part that you fixate on looks circular, but the overall effect is of a spiral. Confirming this is quite challenging, either by scanning your eyes over the pictures, or by moving your finger around it. Trying both is instructive, it suggests how peripheral vision may affect both eye movements and hand movements.

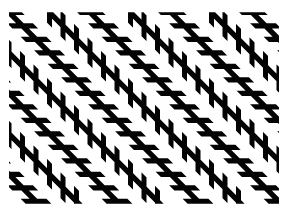

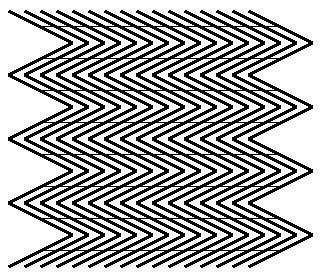

Zollner’s orientation illusion (1860). These, in turn, follow from a sequence of earlier illusions developed by 19th-century psychologists, including Zollner’s orientation illusion of 1860:

The long straight lines are parallel, but they look angled in peripheral vision.

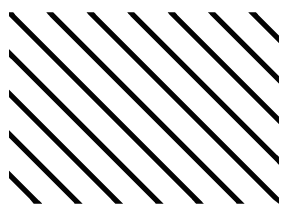

Here are the same long lines, without the short ones:

Now they do appear parallel.

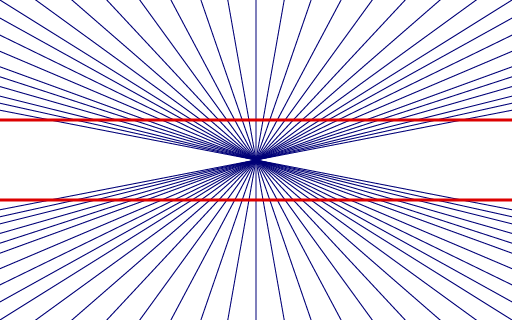

Hering. In the Hering Illusion of 1861, the two parallel lines are straight, but appear curved:

If you fixate on the center of the picture, the red lines look curved. But, if you fixate on any part of the red lines, that part looks straight.

Illusory peripheral motion

Here are some effects where illusory motion appears in peripheral vision, suggesting a peripheral encoding cause.

In the peripheral drift illusion, objects appear to move when you move your eyes:

Trying moving your eyes within one of the circles. Note that the circle you fixate on doesn’t seem to rotate much, whereas the others do.

In the Pinna illusion, you fixate on the center of the picture, and then move your head closer to the picture (or move the picture closer to your head). The circles will appear to rotate.

(This illusion is also described in terms of peripheral vision by Rosenholtz.)

In the Furrow Illusion, the circles seem to be moving in different directions depending on whether you’re looking right at them, or looking to the side:

Here’s one that combines tilt (horizontal lines appear tilted) with illusory motion:

In the Leviant Traffic illusion, motion appears in the outer rings when you fixate on the center of this pattern (you might need to expand the picture to a large size by clicking on it):

This is a version of the MacKay Chrysanthemum.

A further extension is Tyler’s Perceptual Tachyons. This is a very striking and cool illusion that you can view here.

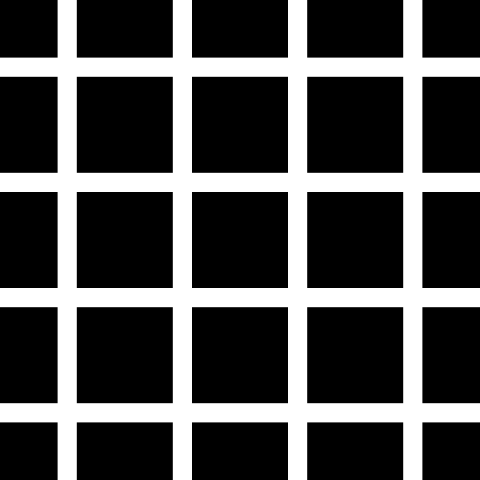

Grid illusions

These grid illusions seem to depend on fixations and peripheral vision.

In the Hermann grid of 1870, dots appear at the corners depending on where you look:

When I generated a metamer for this illusion, it didn’t look different from the original, evidence against peripheral encoding as a cause (but I only tried one parameter setting, and perhaps tried, say, the wrong scale).

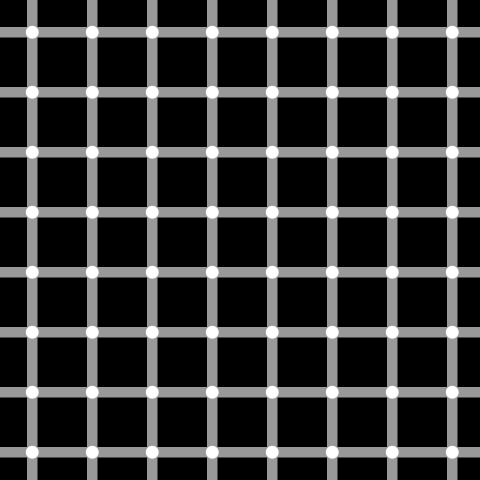

In the Scintillating dots illusion dots appear and disappear as you move your eyes:

The rapid appearance and disappearance indicates that it cannot be due to static peripheral encodings, but it could be due to peripheral motion encodings.

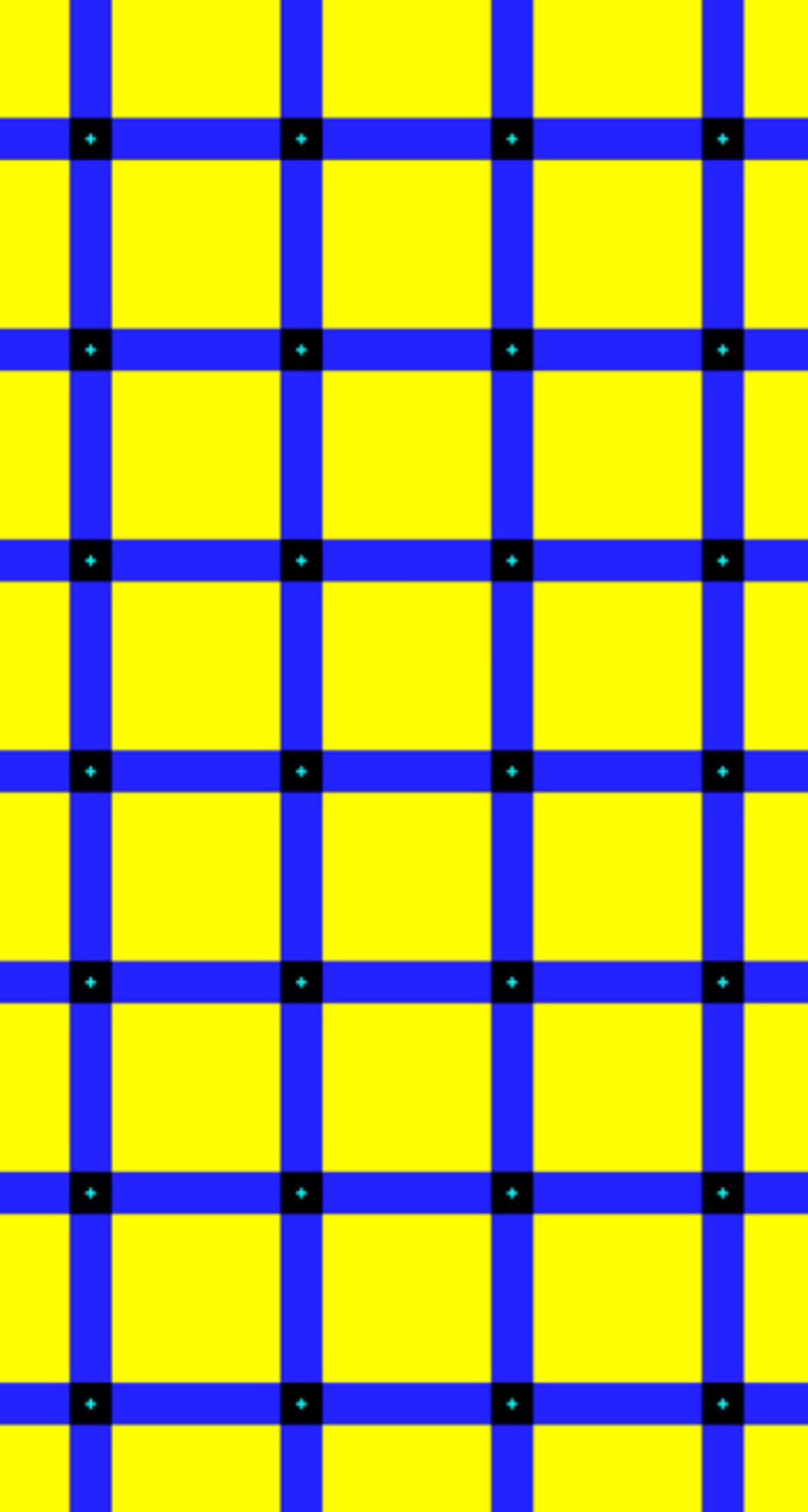

In this color grid illusion by Akiyoshi Kitaoka, crosses appear yellow only in peripheral vision:

This seems to depend a lot on viewing it at the right size.

In the Paperclip Illusion, the straight lines seem to bend into paperclips in peripheral vision:

(Some additional analysis in this thread.)

Illusions due to fragmentary awareness

Here are some visual illusions that, I think, are not due to peripheral visual encoding, but, just to the fact that we must move our eyes to interpret pictures, and we never seem to store the whole picture in our brains.

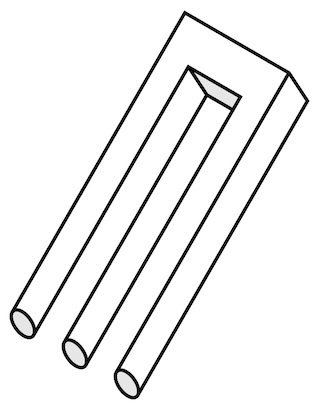

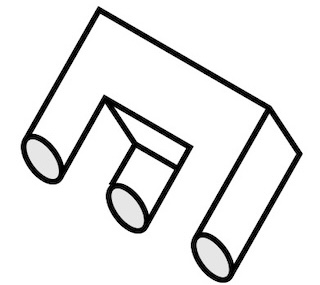

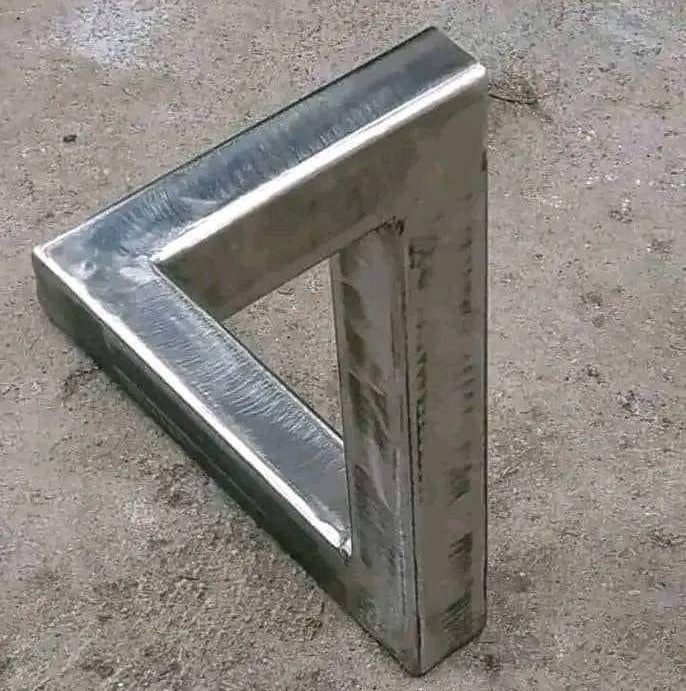

So you’re continually interpreting the current fixation in terms of an abstract notion of the surroundings. This works fine when the 3D scene or picture represents a consistent scene, but what about when the picture is impossible? For example, in impossible pictures, each fixation looks reasonable, but the overall shape doesn’t add up:

If the impossibility is visible within a single fixation, then the picture is much less interesting:

These things get more interesting when the picture looks more realistic:

or more elaborate:

Indeterminate pictures also look beguiling, in that each fixation seems plausible, but it’s never really clear whether or not they do add up to anything:

Here’s a different sort of fixation dependence:

A train appears to step. pic.twitter.com/jJWn2HXImp

— Akiyoshi Kitaoka (@AkiyoshiKitaoka) May 10, 2024

The train appears to move, when it’s standing still. But, if you fixate on the outline of the train, it’s obviously not moving. If you could somehow process the entire shape simultaneously, rather than separately per-fixation, there would be no illusion of movement.

Further reading

For discussion of the illusion of awareness and peripheral vision, see my previous blog post.

For more amazing illusions, see Akiyoshi Kitaoka’s illusion pages, and, relevant to this post, his review of tilt illusions:

- Akiyoshi Kitaoka. Tilt illusions after Oyama (1960): A review. Japanese Psychological Research. 2007.

For discussion of peripheral vision, see:

- Ruth Rosenholtz. Capabilities and limitations of peripheral vision. Annual Review of Vision Science, 2016.

To generate spatial metamers, I used code from this paper, which includes a good background discussion of metamer generation:

- Rachel Brown, Vasha DuTell, Bruce Walter, Ruth Rosenholtz, Peter Shirley, Morgan McGuire, David Luebke. Efficient Dataflow Modeling of Peripheral Encoding in the Human Visual System. ACM Trans. Applied Perception. 2023.

For more discussion of how peripheral vision relates to realistic pictures and to impossible pictures, see:

- A. Hertzmann. Toward a Theory of Perspective Perception in Pictures. Journal of Vision. April 2024, 24(4). [Paper] [Webpage]

Thanks to Akiyoshi Kitaoka and Gavin Buckingham.