Computer Graphics Research As Scientific Modeling of Pictures

In this post I propose a possible view of how to understand computer graphics research. Then I’ll mention some limitations of these definitions and philosophy of definitions in general.

Since I started attending SIGGRAPH, I recall people puzzling over what the subject of the conference is. People thought of computer graphics as the study of photorealistic rendering, yet so many other topics had become big, like image-based rendering and non-photorealistic rendering. In response, people have occasionally proposed their own interpretations and definitions, as have various SIGGRAPH comittees and mission statements over the years. In this post I propose one idea for that discussion.

History and self-definitions

Note: This section is adapted from a paper that has been published in Empirical Studies of the Arts (preprint).

The nature of computer graphics research has changed over the years, and so has the way that the field defines itself.

The very earliest computer graphics focused on line drawing. However, with the availability of framebuffers, research shifted to modeling the physics of light for photorealistic rendering. Some researchers advocated for

The Cornell Box wasn’t just a testbed, it was, arguably, a philosophical statement about the nature and goals of computer graphics research. A considerable body of work today continues to develop both physics-based rendering technologies, and perceptual models of realism.

But much of the early progress was driven by researchers motivated by art and entertainment, and their tools achieved enormous success in the movie and video game industries. These industries cared about artistic usefulness far more than physical or perceptual accuracy. For example, Pixar’s core rendering engines are built on the principles of photorealistic light transport, yet artists employed them to create unrealistic lighting, color, and movement—and none of their films could genuinely be mistaken for live-action photography. The artistic and scientific development of these systems went hand-in-hand—in the words of an early Pixar mantra: “Art challenges technology, technology inspires art.”

As computer graphics research matured, it grew to cover all sorts of applications and visual phenomena, whether scientific visualization, painting, graphic design, cinematography, and so on. This raised the question as to how to define the field, since, for so long, “computer graphics research” had been synonymous with photorealistic rendering. Eventually, a new understanding of the field emerged:

This is the goal that has motivated much of my work: tools for artists and for novices to communicate and make art.

Indeed, in my past experience, SIGGRAPH reviewers would often criticized paper submissions promising completely-automatic image generation, because they do not providing adequate user controls for artists. In this view, we care about photorealism only insofar as it is useful for, say, making movies, or visualizing scientific phenomena.

Convincingly-photorealistic rendering has been particularly successful as an artistic tool: it’s so widespread in narrative movies and television that, it is only slight hyperbole to say that they are inseparable from these art forms. One colleague many years ago wrote on his webpage that his favorite uses were the invisible ones, like adding snowfall to the end of a Bridget Jones movie.

A definition for scientific applications

However, computer graphics techniques have become adopted in other research fields apart from visual art and communication. I’m most familiar with uses in computer vision and in human vision, both of which have occasionally been described in terms of “inverse computer graphics”. Computer vision regularly uses 3D scene representations developed in computer graphics research. Some human vision theories build on photorealistic rendering tools, for example, the idea that human visual cognition uses mental models akin to computer graphics simulations, and theories of material perception based on computer graphics models. In my own work, computer graphics ideas have driven my theories of human line drawing perception, and perception of picture perspective.

How can we describe computer graphics research to allow for these uses? I propose a complementary, third description that makes the relationship to other fields clearer:

This goal is not about making art or communication, but about scientific descriptions of how to make pictures, which, in turn, may be useful to other disciplines. (All pictures are forms of communication, art, or both.) By “generative,” I mean all sorts of computer graphics algorithms from the past 60 years, not just the recent “AI”-based methods, and not simply “descriptive” models. By “video,” I mean all kinds of moving pictures, including animation and film, and their accompanying audio.

This subsumes the classic photorealistic rendering goals (making pictures that look like photographs), but also includes art and design (e.g., making pictures that look like paintings).

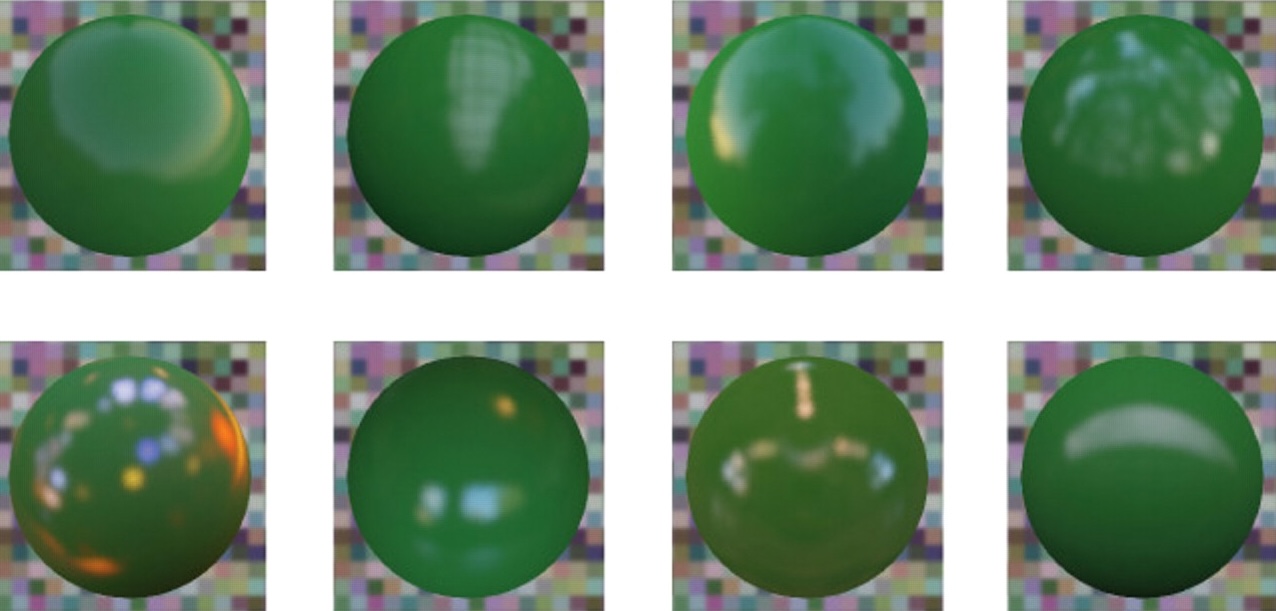

This new goal might sound indistinguishable from other kinds of scientific modeling, but there are subtle, important differences. For example, simulation of fluids in physics and numerical computing aim for accurate prediction of physical quantities, e.g., to test theories and forecast real systems, such as the weather. Such simulations care about predictive correctness, and often employ massive supercomputer computations to run, without producing realistic animations in the end. In contrast, fluid simulations in computer graphics can produce realistic-looking animations very efficiently, often in real-time, even if they give up predictive accuracy by violate physical principles like energy conservation to do so.

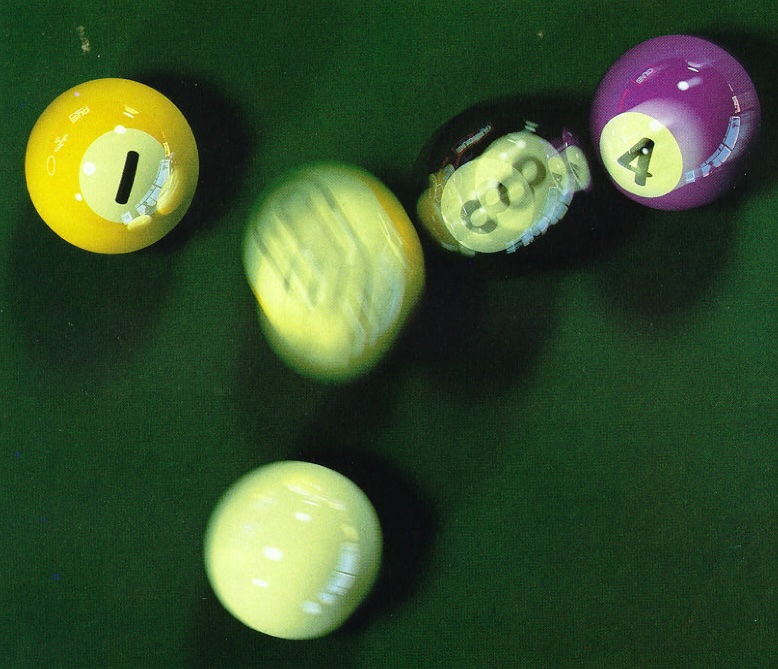

Cole’s 2008 paper provides an excellent case study of computer graphics research as science, that is, as a description of real-world pictorial phenomena: they measured how well computer graphics algorithms predicted human-drawn lines, based on data they gathered with a controlled line-drawing task.

In short, the proposed goals in computer graphics research are:

- Engineering/design: Build useful tools for people to create pictures, video, and other visual media.

- Science: Create generative models of the kinds of pictures and video we see in the real world.

These goals overlap substantially, and, in many cases, one can drive the other. I don’t think you can describe the scope of the field or its impacts without both.

Limitations and gaps

The biggest flaw of my definitions is that they seem to omit some significant topics. Perhaps fabrication fits into my first definition? There used to be a thread of haptics publications at SIGGRAPH. Does computational imaging fit in? If we allow the definition of the field to be fluid, then hard-to-categorize edge cases are inevitable (e.g., those papers on tangible user interfaces), if we allow the definition of the field to be fluid. Such edge cases could be an isolated blip at the conference or the start of a whole new direction for the field.

Another possible flaw is that human and computer vision are the only other fields that I’ve identified as using computer graphics models, but surely there are others?

Computer graphics has also contributed to other fields through non-visual algorithms, most obviously through the development of GPUs and GPGPU now GPUs are having a huge worldwide impact on many fields. But I don’t see this is a continuing theme in graphics research.

What is a definition and why does it matter?

We first learn of definitions as fixed, static concepts. The dictionary tells you what a thing is, then everything in that category follows that definition. This is the prescriptivist notion of a definition. But, as Wittgenstein pointed out, this isn’t how we use words in the real world. If people had been strict about sticking to how they understood computer graphics in the 80s, then it would still be about photorealism, and photorealism only.

Wittgenstein is often paraphrased as saying “meaning is usage:” you can’t tell what a word means without looking at how it is used. For example, how would you define the word “game” or “art”? He argued that categories follow “family resemblances,” sharing many—but not all—attributes.

But I think that formulating these definitions is useful—and not just use nearest-neighbors—and to keep updating them as the field evolves. It’s useful because having a definition helps people understand the field. When you formulate the field in this way, it may suggest new directions or gaps in the research. It can help resolve debates about whether a specific paper belongs at the conference.

Furthermore, having a scientific justification can help with government funding and scientific credibility; both have often been problematic when SIGGRAPH was viewed as just being the R&D arm of the entertainment industry.

These kinds of definitions can overlap with other fields. The vision conferences now regularly publish computer graphics papers, another example of evolving goals. And, I was a little surprised, honestly, when SIGGRAPH 2004 accepted our image deblurring paper.

Of course, the most basic, Wittgensteinian definition of SIGGRAPH is “what is interesting to the SIGGRAPH community.” It originally baffled me as a criteria for what papers to accept, but now I think this is one useful important meta-definition, since it allows the other definitions to change and evolve over time, by including things that don’t seem to fit any of our more-rigid definitions. (The “positive impact” of the paper is probably the meta-definition that I care the most about when reviewing.)

Such definitions are naturally unstable. When the “Escherization” paper was published at SIGGRAPH 2000, one of my mentors shook his head, saying “What, are we publishing any sort of mathematics without any applications?” and another one said on a different occasion, completely independently, “It’s so great that SIGGRAPH is showing that there’s room for these kinds of delightful papers.”

Thanks for feedback from Kavita Bala, Kartik Chandra, Theo Honohan, Tzu-Mao Li, and Yael Vinker.