Why Does Line Drawing Work? A Realism Hypothesis

This page summarizes my new hypothesis about why line drawings work. These ideas were first described in the following paper:

- A. Hertzmann. Why Do Line Drawings Work? A Realism Hypothesis. Perception. 2020. 49(4):439-451. Official paper link, arXiv preprint

The second paper expands on how this hypothesis relates to theories based on edge detection. It is meant to be self-contained, and may be easier to read, though it covers fewer topics:

- A. Hertzmann. The Role of Edges in Line Drawing Perception. Perception. 2021. 50(3):266-275. Official paper link, arXiv preprint

You can also watch a presentation of this work on YouTube.

We begin with a mystery

We have eyes and vision in order to help us navigate and survive in the real world. Evolution gives us abilities to quickly and accurately understand images of the real world. If you see a picture of the forest at night in the fog, you can immediately tell what it is and recognize objects in the scene. Being able to accurately, quickly, and continually understand the world around us helps us find food, avoid danger, and live together with other people. Mistakes in vision–like hallucinating something that isn’t there–can lead to misunderstandings, accidents, and even death.

It’s not too surprising that we can understand photographs, since they look a lot like the real world. But what about line drawings? These look nothing like the real world. We don’t see black pen outlines walking around on white backgrounds. Yet, we can understand drawings just as easily as we can understand photographs. We see shape in drawings rather than just seeing them as marks of ink on a page. Why would this be?

If you can understand real images, you can understand basic line drawings

One influential philosophical theory holds that all artistic styles are learned from our cultures and upbringings. We learn to understand line drawings when we are children, in the same way that we learn to understand written language. Everything about art is a product of our cultures.

Yet, line drawings exist throughout many different historical cultures, even preceding civilization. Cave paintings made by our prehistoric ancestors using outline drawing and are easily recognizable to us today. Moreover, numerous studies with members of tribal societies show that someone who has never seen a picture can understand what’s in a line drawing. So it can’t be something that we learn.

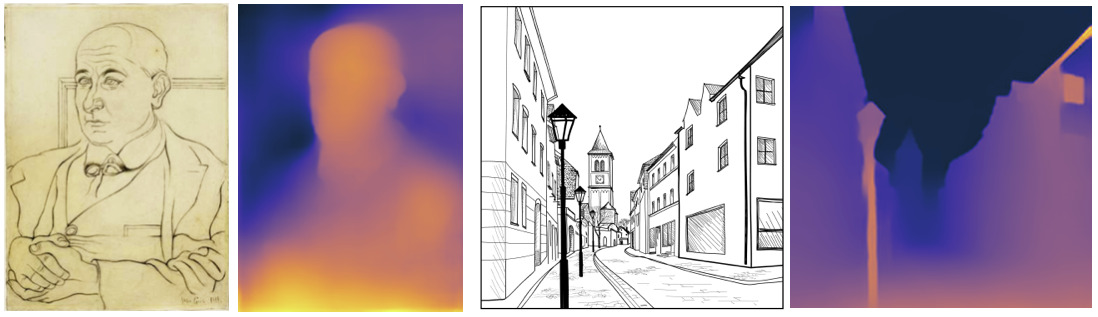

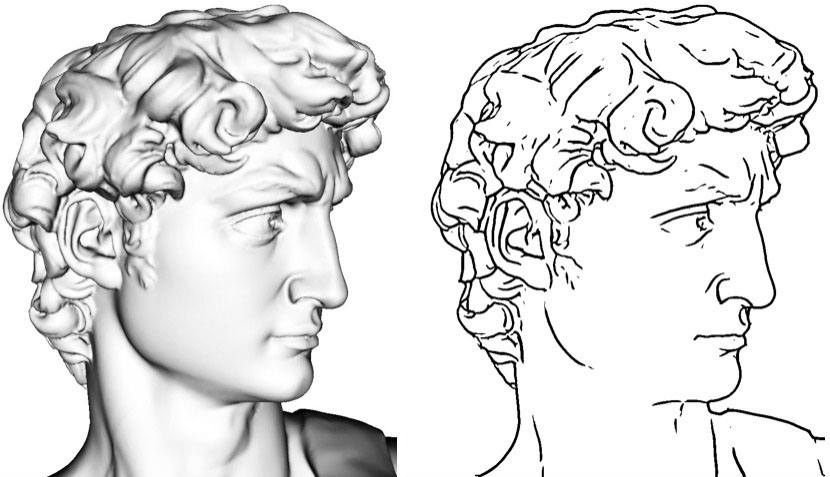

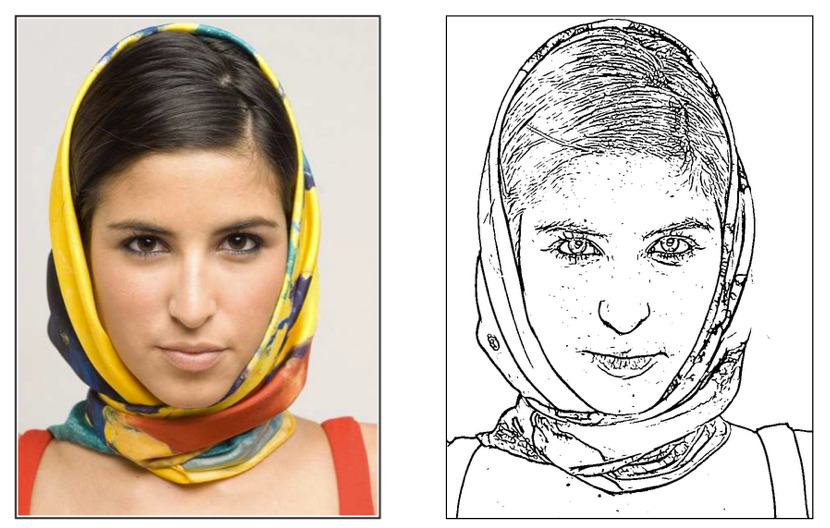

A few years ago, I wondered if perhaps understanding line drawing is a consequence of real-world vision. Specifically, I hypothesized that, if we could train a computer vision algorithm to understand 3D shape in real-world imagery just as well as humans, then that algorithm would also be able to understand shape in line drawings. While our current computer vision algorithms aren’t nearly as good as humans, I still thought I’d try it out. I downloaded a model that was state-of-the-art at the time. This deep neural network predicts relative depth for each pixel in a photograph:

Importantly, this model was solely trained on photographs, not on drawings. And, when I tried it on some line drawings, I got similar results!

This shows that perception of line drawing must be somehow a consequence of real-world perception. But why?

(Many vision researchers have informally hypothesized that line drawing perception is a consequence of edge receptors in the early stages of the human vision system, but I think this is implausible for many reasons.)

Line drawing as Abstracted Shading

It turns out that there’s a way to create line drawings that is based on possible real-world conditions.

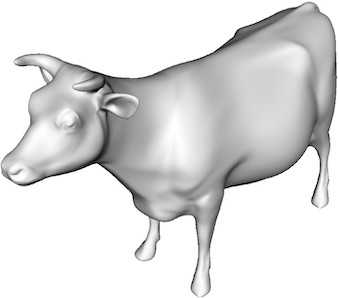

Set up a 3D object in front of you. Paint it white. Turn off all the light sources, except for a headlamp that you wear on your forehead. If the object is a model of a cow, it may look like this:

If we draw a picture of this image with a black pen on white paper, the simplest thing to do is to draw lines through the darkest regions. And that picture might look like this:

We can see that the drawing is, approximately, a plausible real-world image. That is, it’s not something that we’re likely to see around us. But it’s something that we could see in the real world… and we are able to understand realistic photos of things we’ve never seen before-even when the image is corrupted with fog or rain or image noise-and this rendering setup shows how a realistic setup can approximately produce line drawings. This model of line drawing originated in computer graphics research.

| I hypothesize that, for a person who has never seen a picture before, the human visual system interprets a line drawing as if it were a realistic image, with a lighting and material setup similar to those above. |

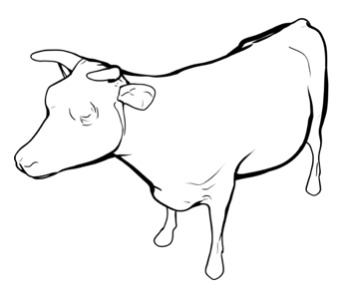

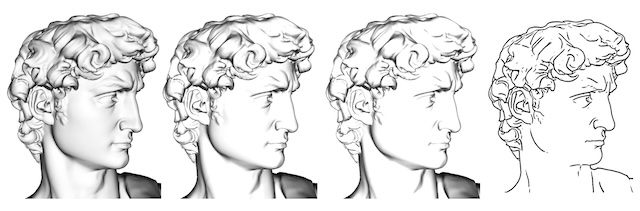

In other words, for a line drawing, there exists a realistic interpretation of the line drawing. When you see the image on the right, you can interpret it as if it were, roughly, the image on the left:

There’s no clear division between realism and line drawing:

This setup works with various different settings of materials and lighting; here are two other possible examples. In each case, the lines are being determined by a valley-detector algorithm (in OpenCV):

This hypothesis doesn’t say anything about how the vision system actually works. It says that, whatever the vision system is doing for photographs, it’s doing basically the same thing for line drawings in the same way.

Future directions

This hypothesis could be tested by brain-imaging experiments with human subjects. I predict that the neural responses to a line drawing will be very similar to those of corresponding 3D renderings. There are some previous neuroscience studies that have been performed comparing neural responses of line drawings to photographs; these methodologies could be used to test my predictions. This could also be used to assess what kinds of lighting and material setups best match line drawings. I don’t have the expertise or resources to perform these experiments, though I’d be interested in talking with people who do. Update: much more recently, I’ve come across this very-related paper, which shows a close relationship between neural/cortical features in line drawings versus photographs; this an example of the methodology that could be used to test this hypothesis using more low-level features than used in that paper.

This theory focuses solely on a very basic line drawing style. In the paper, I discuss how several other types of line drawings-such as white-on-black drawing and hatching-can also be understood as abstracted shading. But the range of visual artistic styles we can understand is vast; we seem to have the ability to visually separate style from content. How do we do this? This probably involves some experience and cultural background, but is not purely cultural.

Abstracted shading references

This theory is based on computer graphics research on abstracted shading. Here are my favorite papers on this topic (I’m biased about the third one):

-

D. DeCarlo, A. Finkelstein, S. Rusinkiewicz, A. Santella. Suggestive Contours for Conveying Shape. ACM Transactions on Graphics. Vol. 22, No. 3. July 2003. Project page

-

Y. Lee, L. Markosian, S. Lee, J. F. Hughes. Line drawings via abstracted shading. ACM Transactions on Graphics. Vol. 26, No. 3. July 2007. Paper

-

T. Goodwin, I. Vollick, A. Hertzmann. Isophote Distance: A Shading Approach to Artistic Stroke Thickness. Proc. NPAR 2007. Project page

Also, a significant precursor is:

- D. E. Pearson, J.A. Robinson. Visual communication at very low data rates. Proc. IEEE. 1985. Paper.

For a more complete tutorial/survey on line drawing algorithms, see:

- P. Bénard, A. Hertzmann. Line Drawings from 3D Models: A Tutorial. Foundations and Trends in Computer Graphics and Vision. Volume 11, Issue 1-2. 2019. Official paper link, arXiv preprint