Why Edge Detection Doesn’t Explain Line Drawing

Note: a revised and updated version of this post has been published in Perception, or see the preprint: http://arxiv.org/abs/2101.09376. I think the paper expresses these ideas much more carefully and clearly than this old blog post.

Why do line drawings work? Why is it that we can immediately recognize objects in line drawings, even though they are not a phenomenon from our natural world. Numerous studies show that people who have never seen a line drawing before can understand a line drawing; line drawing is not something you have to learn to understand.

A classic answer to this question is what I will call the Lines-As-Edges hypothesis. It says that drawings simulate natural images because line features activate edge receptors in the human visual system. From what I can tell, this belief is widely shared among vision researchers; many people bring it up whenever I discuss line drawing perception, as did many commenters on a recent Twitter thread. A generalization of this is that lines correspond to some internal representation, such as neurons that fire on object contours, which I’ll call Line-As-Internal-Representation and also discuss here.

The purpose of this blog post is to explain why I think you should be skeptical of the Lines-As-Edges hypothesis. Many vision researchers and tweeters state some version of the hypothesis with uncritical certainty, as if the problem is solved, and I seem to have a hard time convincing them otherwise. It has the feeling of unquestioned, received wisdom: everyone knows that this is true, and sees no need to question it.

I don’t claim that Lines-As-Edges is necessarily false, but I do argue that it is unsatisfyingly incomplete. In a recent paper (preprint version), I proposed a totally different explanation for line drawing. My explanation is also incomplete, but I think it provides some potential benefits. It is also compatible with Lines-As-Edges, so they could both be accurate.

What is the Hypothesis?

In order to discuss the hypothesis, we need a clear statement of what it actually says. Yet, for being so widely accepted, it’s very hard to find such a statement. Although the idea has been “in the air” for decades, the only real statement of Lines-As-Edges that I’ve found is by Sayim and Cavanagh (2011), and even they point out big gaps in the theory.

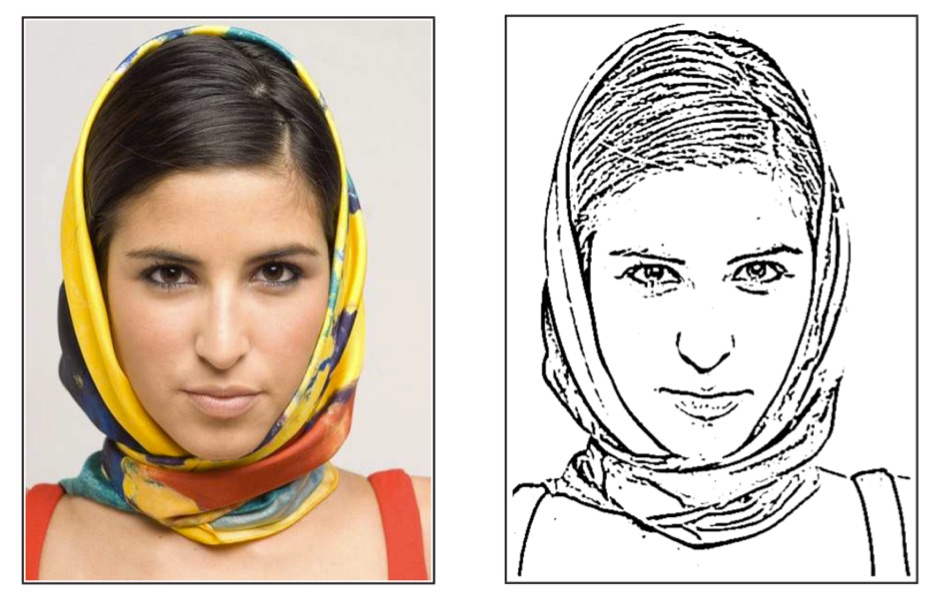

The idea arises from two compelling observations. First, since the pioneering experiments of Hubel and Wiesel in 50’s and 60’s, we know that the visual cortex includes cells that are responsive the edge patterns. In short, one of the first things that happens to the signal from our retinas is edge detection. Second, if you run an edge detector on a real image, and threshold the responses, then you often get something that looks like a line drawing. Here is one example, a Difference-of-Gaussians from the XDoG paper:

The most basic statement of the hypothesis is: the lines in a line drawing are drawn at natural image edges, where an edge receptor would fire. These lines activate the same edge receptor cells that the natural image would. Hence, the line drawing produces a cortical response that is very similar to that of some natural image, and thus you perceive the drawing and the photograph in roughly the same way.

Problem #1: What about all the other features?

The most basic statement of the problem with Lines-As-Edges is that the human visual system isn’t just an edge detector. You can see colors, you can see absolute intensities. You can tell the difference between a thin black line and the silhouette of a dark object against a light background; we have both kinds of receptors in the primary visual cortex, as well as others. Yet Lines-As-Edge supposes that the vision system discards all of this other information present in an image, for just this one special case. Why?

Discarding some features and not others seems arbitrary. Surely we could discard some other random collection of features and get other plausible image interpretations out of them.

I’ve never heard a plausible answer to this question, or even seen a concrete attempt to answer it.

Problem #2: We can’t see internal representations

A slightly different statement of the hypothesis is what I’ll call Lines-As-Internal-Representations. The idea is that we have neurons that activate for object contours and similar, and that line drawings directly activate these neurons. Lines-As-Edges is a special case of this hypothesis.

I don’t understand this claim at all. You can’t just show some visualization of some arbitrary neuronal activation to the brain and expect that those neurons will fire.

Suppose you have an algorithm that computes y=f(x), and the computation involves an intermediate variable: w=g(x); y=h(w) so that f(x)=h(g(x)). You cannot expect to get the same result if you run w=g(x); y=f(w). The types might not even match. In terms of neural networks, this theory seems to be proposing that you can take filter output i from network layer j and directly feed it as input to the network. How would this even work?

Problem #3: What is the benefit?

To really understand vision, we have to reason about more than just the visual cortex. If human vision was just edge detection, then we would have already figured out how vision works a long time ago. Understanding vision by looking only at neurons is like trying to understand how a computer program works by looking only at the compiled machine instructions without reasoning about what the program is for.

The human vision system is extraordinarily robust at what it does: help us navigate and survive the world by providing us high-quality inferences about what we see. This process is extremely robust to all sorts of misleading and noisy sources of information. Any explanation for how it can be fooled into inaccurate perception requires a compelling explanation in terms of the goals of the vision system. For example, Adelson’s checkerboard illusion indicates that the visual system is much more interested in inferring actual reflectance rather than incoming irradiance. Most visual illusions exploit inductive biases of the vision system: biases that are useful in normal situations, even though they create unexpected outcomes in cases that didn’t matter that much to our Pleistocene ancestors. Our Pleistocene ancestors probably didn’t need to consciously reason about relative irradiances.

Lines-as-edges posits a massive “failure” of visual inference—hallucinating shape where there is none—without providing any corresponding beneficial inductive bias. We don’t actually believe the shape is there due to the dichotomous nature of images, but the inference of shape is still wildly erroneous under this hypothesis.

Problem #4: Visual art isn’t just line drawings

Suppose we add color to a line drawing:

Now you get a sense of the color of the object, and not just its outlines. How would one generalize Lines-As-Edges to account for these different types of depiction? The visual system is no longer ignoring everything aside some gradients; it’s now paying attention to some colors (and not others).

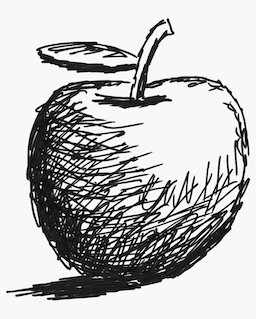

Or suppose we add hatching:

How does Lines-As-Edges now explain our perception of this style?

Artists depict objects in a seemingly-infinite combination of outlines, colors, hatching, stippling, painting, and so much else. To account for this, the Lines-As-Edge hypothesis would need to argue that somehow the visual system recognizes each style and identifies which features to ignore and which to keep. Again, this may be true in some sense, but it should be clear that Lines-As-Edges is far from being the end of the story.

Alternatively, it could be that untrained observers cannot understand these drawings; I am not aware of any studies on this topic, but I think it unlikely, since studies have shown that untrained observers can understand line drawings and they can understand photographs.

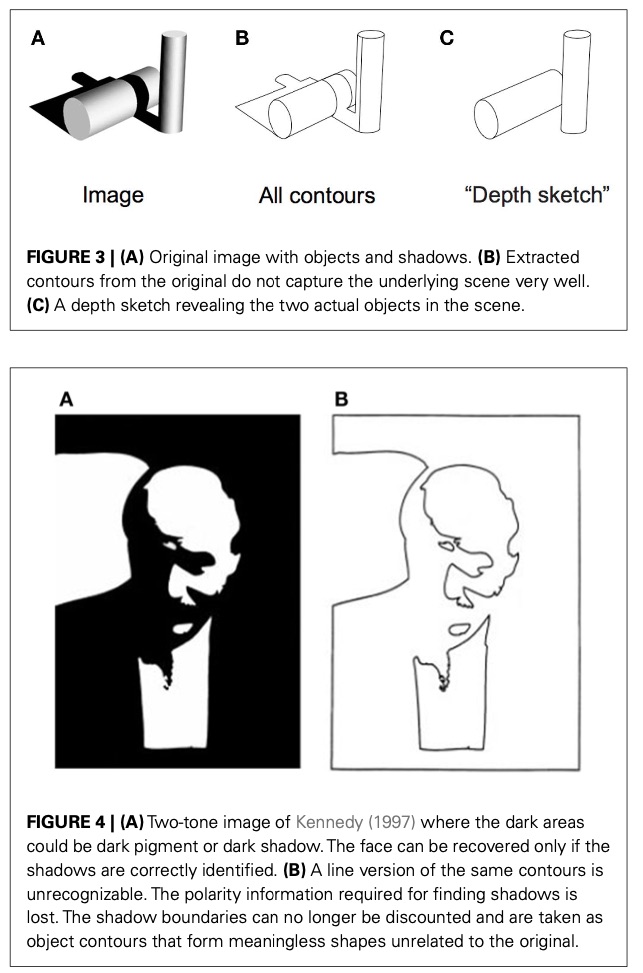

Problem #5: Edge detection is not a line drawing algorithm

Lines-As-Edges starts from the observation that edge detection can produce line drawings. But it often doesn’t. Here are two examples from Sayim and Cavanagh:

That said, I think that Lines-As-Edges could be modified to account for this, combining ideas from Judd et al. (2007) and my paper. The modified hypothesis would be: the visual system interprets line drawings as if they were edge images of a matte white object under headlight illumination, or averaged over a range of similar illumination. To my knowledge, this modified hypothesis is novel; except that Judd et al. make very similar assertions that come extremely close to this. However, this modification does not fix the other problems listed above.

Alternatives

I believe my hypothesis proposes a different way to think about this, without the problems above. This hypothesis is compatible with Lines-As-Edges, while answering many of these questions. My hypothesis has its own gaps, but I think it nonetheless it provides a promising way forward on these questions.

See the end of this follow-up post for one possibility about how my hypothesis could incorporate edge information.