Changing Melodies: Art and Research are Often Open-Ended Exploration

This blog post is adapted/revised from parts of my ICCC 2022 paper, which borrowed from previous blog posts.

How does an artist decide what to do? We often think of artists as goal-oriented: an artist has an idea, a vision, or inspiration, and then they produce an artwork based on that inspiration. Likewise, we sometimes think of researchers and scientists as first identifying a problem to solve, and then executing on a solution.

I believe that both these conceptions are often wrong.

| Very often, the best art and the best research arises from open-ended exploration: when the artist or the researcher starts with an idea without knowing where it will lead. |

We often interpret art and research works as though they had been intended all along. They are often they are presented that way. But often the apparent “intentions” came during the work, not before it.

Understanding this has been liberating for me when I paint, and I think it’s essential to understand when doing research, managing or funding research, and building tools for artists.

Art and Research Don’t Have Simple Goals

When I started painting again in 2019, I started each painting with a goal, and often failed to achieve that goal. But sometimes my “failures” became my favorites, where I’d created something surprising and more interesting than my original intention.

I embraced the idea of not needing to achieve a specific goal, but starting a painting only with an intuition that “this looks like an interesting thing to try.” I then read Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned which provided many vivid examples of accidental innovations. While I disagree with the book’s theory of exploration, I found its emphasis on open-ended exploration as a practice in itself very inspiring.

Then, in my readings and viewings, I began to notice more quotes from artists and scientists who describe their processes in open-ended terms, which I’ve been collecting since then. Here are a few of those examples.

Examples from Abstract Art

Artists carefully consider and develop their artistic processes; process is not merely incidental to outcomes. In the context of the fine art world, Jerry Saltz writes “serious artists tend to develop a kind of creative mechanism—a conceptual approach—that allows them to be led by new ideas and surprise themselves without deviating from their artistic principles.”

Pablo Picasso: “I don’t know in advance what I am going to put on canvas any more than I decide beforehand what colors I am going to use … Each time I undertake to paint a picture I have a sensation of leaping into space. I never know whether I shall fall on my feet. It is only later that I begin to estimate more exactly the effect of my work.”

Francis Bacon: “one has an intention, but what really happens comes about in working … In working, you are following this cloud of sensation in yourself, but don’t know what it really is.” That is, his work starts with an initial intention, but it quickly gives way to surprise and discovery. He operates on the high-level goal of making paintings, but the specific intentions of those paintings are not fixed in advance.

Here’s Gerhard Richter describing his process:

In a separate interview, Gerhard Richter said “I want to end up with a picture that I haven’t planned,” for which he uses a process that involves chance. “There have been times when this has worried me a great deal, and I’ve seen this reliance on chance as a shortcoming on my part.” But, “it’s never blind chance: it’s a chance that is always planned, but also always surprising. And I need it in order to carry on, in order to eradicate my mistakes, to destroy what I’ve worked out wrong, to introduce something different and disruptive. I’m often astonished to find how much better chance is than I am.”

Amy Sillman on the practice of abstract art: “The art-making process is a recording of these restless interactions … Perhaps this is particular to abstract painting, where you often don’t really ‘know’ what you’re doing, and so you are doomed to work in between hoping and groping. In abstraction, time goes by in fits and starts, with resistance of materials being part of that time. … I know of no artist who is attempting to make something more beautiful, but I do know many artists who are looking for a form that ‘feels right’ without knowing why. Maybe it’s just satisfying to see something productive come of feeling like an idiot and the accompanying feeling of embarrassment.”

Computer Art. People often think of computer art as somehow mechanical or automatic. But the earliest generative art pioneers talk about how they use it as a tool for discovery and surprise. Here are two pioneering computer artists, who began making generative art with random numbers in the 1960s. Charles Csuri: “When I allow myself to play and search in the space of uncertainty, the more creativity becomes a process of discovery. The more childlike and curious I become about this world and space full of objects, the better the outcome.” Vera Molnar: talks about using randomness and “the thing that is not planned” to find surprising solutions, that she uses her generative art code to find surprises. (I had a better quote from her but cannot find it at the moment.) Helena Sarin: “I love making art because I love to surprise myself.”

Filmmaking

Ed Catmull quoted a movie studio executive saying that “our problem is not finding good people, it’s finding good ideas.” And Ed questioned this, asking around whether it is more important to have good ideas or good people? He found that audiences were split in their answer to this question.

He concludes that the answer is very clear: “If you have a good idea and give it to mediocre people, they’ll screw it up. If you give a mediocre idea to a good group, they’ll fix it. Or they’ll throw it away and come up with something else.”

Two examples from rock music

In so many histories of art I’ve read or watching, at some point someone says something like “we didn’t set out to invent” hip-hop or heavy metal or whatever.

Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned recounts how Elvis Presley came up with his signature sound. According to his guitarist: “All of a sudden, Elvis just started singing this song, jumping around and acting the fool, and then Bill picked up his bass, and he started acting the fool, too, and I started playing with them. … [the recording engineer] stuck his head out and said, ‘What are you doing?’ And we said, ‘We don’t know.’”

Get Back. Many illustrations appear in the recent documentary Get Back. The documentary follows The Beatles in January 1969 when they were under enormous pressure to write, record, and perform an entirely new album in only a few weeks’ time. In one clip, Paul McCartney comes into the studio and improvises random sounds on his guitar, until the kernel of a new melody and chorus emerge. We then see The Beatles experimenting with different approaches to refining the song. Ultimately, this song became the hit single “Get Back.” The song arose from the high-level goal of making a good song, and then going into the studio and exploring until something emerged.

At one time, The Beatles considered making it a protest song about anti-immigration policies. In this version, the chorus “Get back to where you once belonged,” which came from the original jam session, had a totally different meaning than in the final song. Had they released it as a protest song, surely many listeners would have inferred that the song originated from the political message, when in fact the song came before the message.

This example illustrates two kinds of goals in a work. There is the initial, high-level goal (“write a good song”), and the apparent goal or intent of the final song (“protest immigration policies”). As noted by Bacon, there is often also an initial idea or goal that begins the work, but this initial goal may be discarded along the way.

Creative Exercises

There are some explicit processes that codify exploration.

Improv theatre is an entire art-form of developing theatre pieces from scratch before a live audience. One of my improv teachers compared it to driving on a dark foggy road in the night, with your headlights illuminating only the road immediately in front of you. All you can do is to keep driving to the next visible spot and continuing from there. You cannot plan, you can only take it one step at a time. Yet, somehow even amateur improv actors can create compelling performances out of nothing. Driving on a foggy night in search of any interesting destination seems like an excellent metaphor for the creative process in general.

The use of creativity exercises and Surrealist techniques illustrate the importance of strategy and starting point. Exercises like Exquisite Corpse and automatic drawing can lead to entirely different outcomes each time.

Research

Numerous examples of significant scientific discoveries came about somewhat “by accident,” or an unplanned series of discoveries: penicillin, benzene, Uranus, even computer science itself.

In the words of Isaac Asimov: “The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not ‘Eureka’ but ‘That’s funny…’“

It is often said that the most important skill in research is figuring out what problem to work on, and figuring this out is part of the exploration. When I was in grad school, Richard Hamming’s You And Your Research really affected my understanding of research. He describes a very focused search for both the right problem and the solution. The “lean start-up” idea seems similar as well.

The distinguished mathematician Michael Atiyah, when asked “How do you select a problem to study?”, responded “I don’t think that’s the way I work at all. … I just move around in the mathematical waters … I have practically never started off with any idea of what I’m going to be doing or where it’s going to go. … I have never started off with a particular goal, except the goal of understanding mathematics.”

Image Analogies

Many of my projects basically solve the problem they set out to. Sometimes they solve the problem, but having discovered totally different techniques than we started out with. Some projects fail entirely to solve any problem and get abandoned.

However, some of many of my favorite papers developed accidentally—most notably, our “Image Analogies” paper.

For that project, I initially proposed developing a semi-automatic system to assist artists in stylized rotoscoping, inspired by having recently seen Bob Sabiston’s “Snack and Drink” at an animation festival.

Here a few of the slides from the internship proposal presentation that I gave at the beginning of the summer:

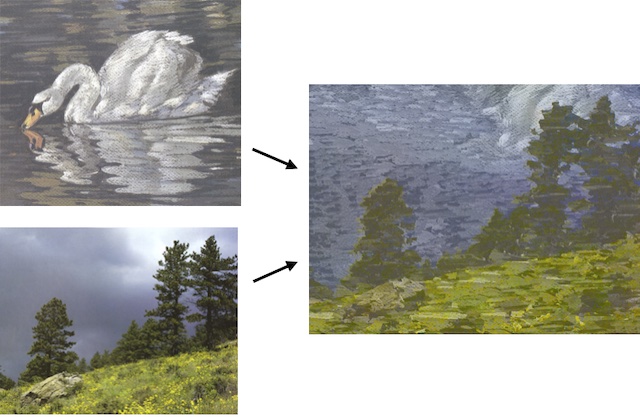

I started working on curve filtering for rotoscoping, and, in collaboration, one idea led to a different one which led to a different one, eventually leading to a very different project, namely a way to “learn” image transformations from examples (by guided texture synthesis). Since it was my thesis topic, we applied it to artistic image stylization, such as learning painting, pen-and-ink, and pastel styles:

along with various other filters.

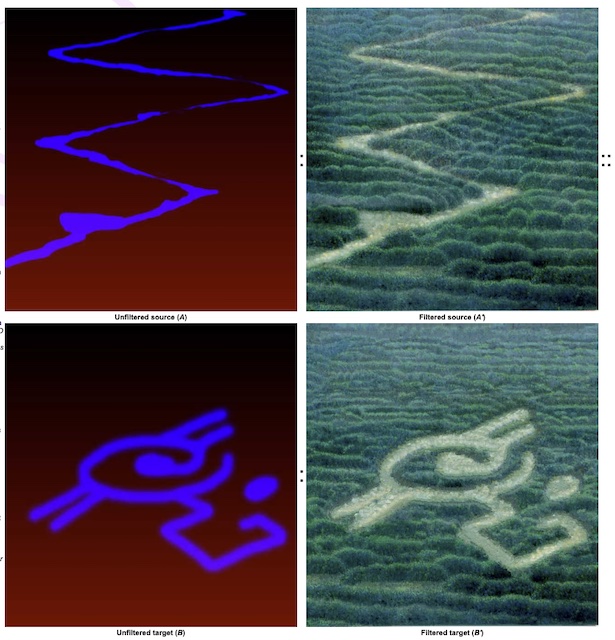

One we had a technique for learning filters, we started to find applications for it everywhere. At one point while working on the project, I walked into a friend’s office and saw this painting by Masaaki Miyasako on the wall:

which immediately gave me the idea for controllable texture synthesis:

which we could then make more complex and also interactive:

(The interface was built by Chuck Jacobs.)

I wanted to call the paper “Learning Image Filters,” but my coauthors preferred the title “Image Analogies.”

After the paper was published in 2001, someone downloaded our software and applied it to an application we hadn’t thought of: generating terrain from maps.

None of these ideas were planned. They were all the product of a focused exploration and constantly throwing out the old goals when better ones appeared.

I’ve heard from other colleagues about projects that had similarly circuitous routes. The PatchMatch algorithm began as an attempt to summarize videos. DALL-E (someone once told me) began as an attempt to improve language models using image data.

At the time, we translated the title of the painting “変奏曲” as “Changing Melody” or “Musical Improvisation.” While Google Translate now gives me a different translation, those titles and the zig-zag path seems like a good analogy of exploration.

Thanks to Heidi McDowell for pointing me to the Amy Sillman essay.