Useful Ways to Talk About of Art (Definitions, Part 2)

In Part 1 of this series of essays, I described problems with our commonplace ways of talking about art, and recommended avoiding the evaluative usage of “art.”

In this essay, I make some more recommendations about how to talk about art.

Don’t Worry About “Is It Art?”

“Is it art?” is a boring question.

Here’s a simple rule-of-thumb. If someone asks “is this art?” about something that someone made—and they’re asking seriously, not as a gag—the answer is almost certainly “yes.” Asking “is it art???” might have seemed like a serious provocation back in school days, but not any more. As artist Jason Salavon commented on one of my posts, “I don’t think ‘Is it art?’ is a question the art world spends much time on nowadays.”

Almost anything could be art, but what we care about is how it functions as art: is it good in some way? Does it provoke ideas, emotions, experiences, or something else? Is it ethical or moral? Don’t ask “is it art?”, ask “is it good in some way?” or, better, some more specific question than that. The useful questions are subjective. If someone wants to claim that their pizza is art, that’s fine, but the real questions are how beautiful the pizza is, or creative, or expressive.

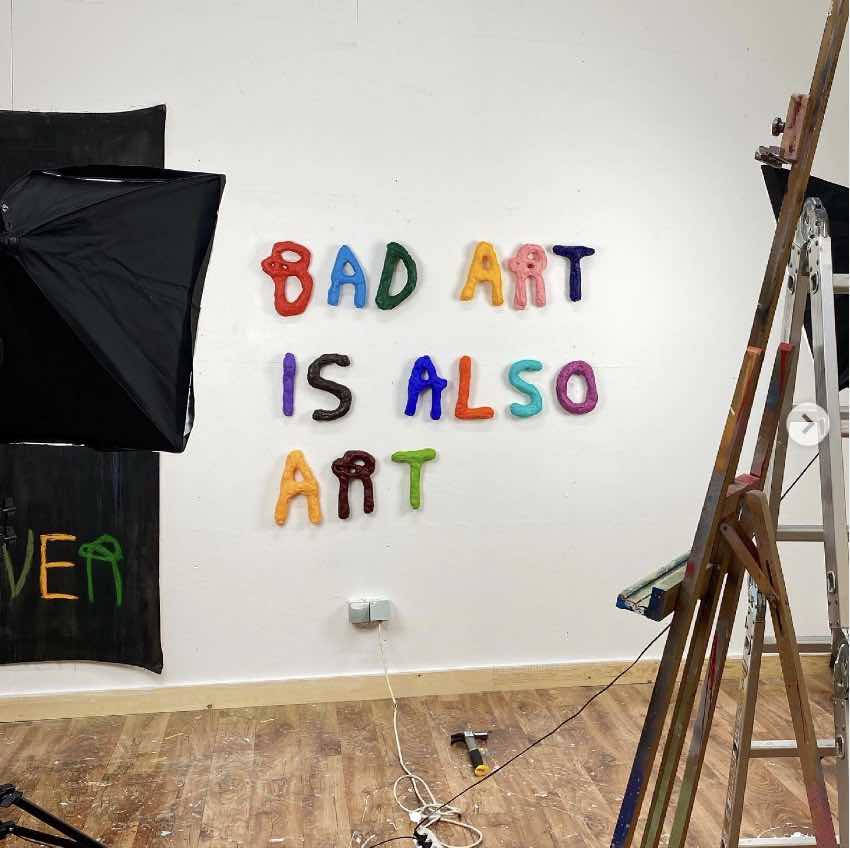

I prefer to use the word “art” as an empty vessel: it’s whatever people want to create as art. The bar for making art is very low. A preschooler drawing with crayons is an artist, even though there few people in the world that will appreciate their art. The bar for making art that lots of people care about is much higher, and subjective.

This is not meant to be a careful and precise philosophical definition of art, but one that is useful in practice, a heuristic for better discussions. We should spend less time discussing whether something is art, and more time discussing what value it has: do you like it? is it beautiful? interesting? provocative? unethical? etc.

I’m essentially describing a simple version of Jerrold Levinson’s Institutional-Historical Theory of art: “an artwork is a thing (item, object, entity) that has been seriously intended for regard-as-a-work-of-art — i.e., regard in which any way preexisting artworks are or were correctly regarded.” An artist can pick up a rock and declare it to be art. I recommend The Art Question if you’re interested in more information on the nuances of that definition and what it’s trying to say.

Note that this is a separate discussion from whether computer algorithms could be artists.

Use precise terms/phrases

People often treat “art” and “artist” like they are monolithic, unitary terms, when there are so many different kinds of art and artists; confusion occurs when people from different communities interact.

For example, the contemporary art world would not view Pixar concept artists or character animators as artists. In the computer animation world, they are revered as artists. But some “Technical Directors” have artistic jobs too, but don’t have the same high status, and contemporary art isn’t part of either of the way they talk about art. For the stereotypical common person, taping a banana to a wall isn’t really art, because there’s no technical skill (“craft”) involved.

In computer graphics research, “artist” is used as a generic term. Papers described systems used by artists, and are to be evaluated by artists. When I presented my stylization research in faculty interviews in 2001, many people asked skeptically: “have you shown this to any artists?” I always wondered: what kind of artist should I show it to? Contemporary avant garde artists, commercial designers, concept artists, untrained “outsider” artists, calligraphers, felters, potters, jazz trumpeters? Even within one of these groups, tastes and preferences may vary widely. I could have asked 5 artists and got 5 opinions. All 5 of them might have despised computers anyway; you would be unwise to ask Hayao Miyazaki to evaluate your new computer animation tool.

My advice here is: when talking about art and artists, be specific, if it’s not obvious from context. What kind of art/artist are you talking about? Contemporary/fine art? Animators? Cirque du Soleil performers? etc.

Likewise, the way people use the phrases “definition of art” and “what is art” often perplex me, because people seem to mean totally different things by “definition.” Different books on “what is art?” don’t just have different answers, they seem to be answering different questions entirely. Are we talking about a classificatory definition, how artists work, the way art functions, or something else? When people talk about the “intent” of a work, do they mean the artist’s goal vs. message of the work vs. the intention to make art?

Avoid these vague, overloaded terms and be specific.

Are Better Definitions Possible?

On two separate occasions when I’ve lectured about whether computers can be artists, a computer scientist raised their hand and said “Why don’t you just look up the definition of art? Then that will tell you whether computers can be artists.” As if these definitions are written in axiomatic language, inscribed in the Book of Standards by some formal Académie.

All of our definitions walk a line between descriptivism and prescriptivism: we simultaneously enforce meanings for words based on their definitions, while updating definitions based on real-world usage. Philosophers attempt to define “art” based on how people use the word, but the usage keeps changing. Sometimes these definitions have an agenda, slyly redefining “art” to incorporate the avant-garde of their day. But so far, the philosophers I’ve read have concluded that no simple definition is possible.

Good defintions of art could help us navigate future debates and discussions around art, helping us to understand how new technological and societal developments work as art. Some kinds of defintions, like Wittgenstein’s “family resemblances” or Dutton’s “cluster concepts”, provide useful categorizations of attributes for describing those things we call art today, but don’t seem to provide much guidance for helping people grapple with new forms of art.

I believe that a definition of art needs to reflect the way art exists as a function of the community around it. Classical “institutional theories” of art from George Dickie, Arthur Danto, and Jerrold Levinson assume an evolving but singular definition of art, rather than one that varies between cultures and communities. Art exists in the context of a community/culture, as evidenced by the names of old movements like “New Media,” and “Modern art” or the “Young British Artists”—who are now entering their 60s; these are the artworld equivalents of Oxford’s “New College”). Instead of “the artworld,” it’s really “the artworlds.” Or, to use a phrase from Larry Shiner, “systems of art.”

I believe it’s possible to produce more precise and accurate definitions of art, but they won’t be simple one-sentence definitions, to capture all the different kinds of art and different roles across different cultures and time, maybe something more of a multipart beast.

In my next blog post, I talk about some of the important eras that inform our current notions of art, a notion that I think could inform better definitions.

Readings

This post includes ideas from two books that shaped my understanding of the philosophical definitions of: The Art Question by Nigel Warburton, and The Art Instinct by Denis Dutton, briefly here. As a starting point, here’s an initial version of an essay from the The Art Instinct.

Thanks to Rich Radke, Juliet Fiss, Craig Reynolds, Rob Pepperell, and others who commented.