Creative Explorations with DALL-E 2

Note: A revised, shortened version of this post is online at The Conversation, and reposted at other sites like FastCompany.

I’ve been playing with DALL-E 2, a new text-to-image demo from OpenAI. DALL-E 2 is so much fun. It’s a rabbit-hole of creative play and a glimpse into future power tools for imaging. With it came all the usual bad takes of, on one hand, AI making artists obsolete, and, on the other, AI art not being art at all. Nonetheless, DALL-E challenged my understanding of where we are with computer-generated imagery and computational creativity.

Here are some of the image series that I’ve created with DALL-E:

- Images in the styles of contemporary and modern artists: Facebook, Twitter.

- Three architectural series, made with Manuel Ladron de Guevara:

- Reimagining classic computer graphics imagery: Facebook, Twitter

- Portraits: Facebook, Twitter

- Sheet Music: Facebook,Twitter

And, for more, see my AI-art Instagram (@aaronhertzmann_aiart).

Check them out!

This post shares some of my observations, and what DALL-E tells us about creativity and the future of image manipulation. Many people get the impression from these results that DALL-E can do anything and that it makes artists obsolete. I don’t think either of these things are true, but it is groundbreaking nonetheless, a vivid indication of transformational technologies to come.

My experimentation has been a form of creative exploration. We often have the illusion that, when making art, an artist begins with a concrete goal and then executes on it. But, in many creative practices, one doesn’t plan for a specific, concrete goal. Instead, one idea leads to another which leads to another, which leads one into new ideas completely unexpected from the starting point. DALL-E accelerates this process, so you can iterate on certain kinds of visual ideas in minutes instead of hours, days, or weeks. While DALL-E 2 isn’t a good tool for achieving very focused or concrete tasks, it is an extraordinary power tool for creativity.

I am immensely grateful to Aravind Srinivas (via Alyosha Efros) for providing me access to DALL-E before it was opened up to the public.

What it does

DALL-E 2, like the previous text-to-image systems, generates an image from a piece of text. For example, when some friends and I gave it the text prompt “cats in devo hats”, it produced these 10 images:

These images come in different styles, and nearly all of them look plausibly like real professional photographs or drawings; the algorithm does not know quite what a “Devo hat” look like, but it’s close. I shared this one on social media:

These images come in different styles, and nearly all of them look plausibly like real professional photographs or drawings; the algorithm does not know quite what a “Devo hat” look like, but it’s close. I shared this one on social media:

Art hasn’t felt this easy since the invention of the digital camera.

What it can and can’t do

Even among all the recent progress, DALL-E 2 seems like a significant advance. It isn’t just making indeterminate artistic imagery or realistic images in a few classes, or other artistic kinds of images; it produces many kinds of complex, high-quality realistic and artistic images.

The initial images shared by OpenAI—and by the influencers they gave first access to—gave the impression that OpenAI could do anything, because it could do so many things. It could make things like “Underwater shot of a baby goat’s head eating a carrot, water bubbles, particulate, extremely detailed, studio lighting”:

Often, the best text prompts themselves demonstrated tremendous creativity on the part of whomever used them, like “An IT-guy trying to fix hardware of a PC tower is being tangled by the PC cables like Laokoon. Marble, copy after Hellenistic original from ca. 200 BC. Found in the Baths of Trajan, 1506”:

But there is some selection bias going on here. Hundreds of people are typing all sorts of zany and creative prompts into DALL-E. Only a fraction of those prompts produce awesome results; many don’t look very good. But only the awesome results are getting shared and going viral.

As with any good artist, we’re seeing just the very best results publicly, not all of them. Even if every image that Claude Monet shares looks good, this does not mean he can make a good image of any style or subject.

A lot of the academic discussion around text-to-image focuses on compositionality, and DALL-E’s difficulty with concepts like “A red cube on top of a blue cube”. This blog post gives a balanced analysis of some of the things that DALL-E does and doesn’t do well, and this report discusses some specific tests of compositionality that DALL-E mostly fails at.

OpenAI has been very up-front about many of the problems with DALL-E, and it’s worth reading their initial assessment of potential harms, including the discussion of visual synonyms and bias.

But I found DALL-E’s ability to compose concepts really stunning. For example, I could ask for, say, candid Polaroids of a polar bear’s vacation, and not only would it generate a realistic polar bear, but it would look like an awkward holiday picture with Polaroid photo processing. And then if I tried “candid Polaroids of a clown brunch”, I would get ten high-quality, very different pictures of clowns having a good time at brunch; I could easily imagine these pictures stuffed in a shoebox in the back of some ex-clown’s closet.

An example of making a complicated image

Suppose you have a specific task in mind; what’s involved in achieving it? Here’s one example of how it looks at present.

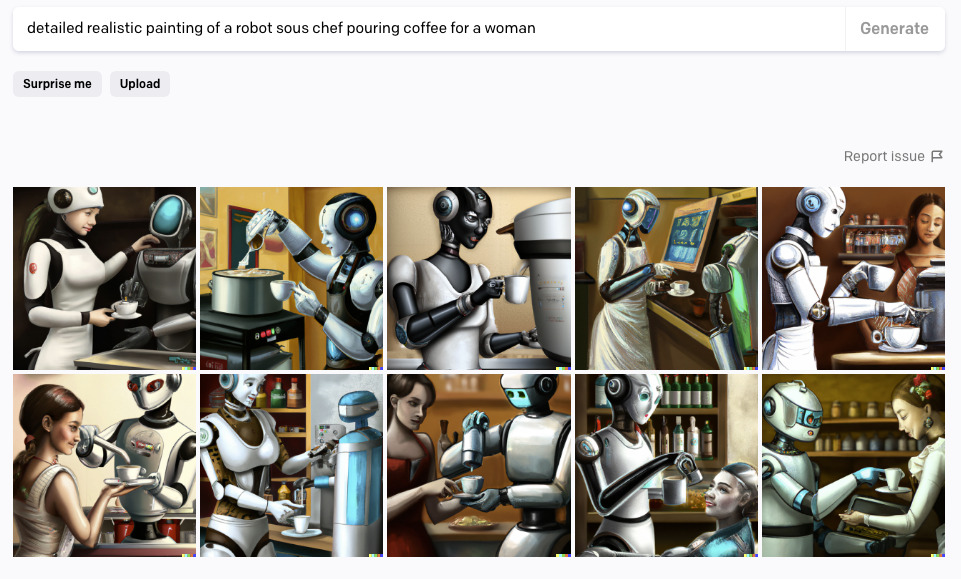

A roboticist colleague recently asked me for images of her with a robot, in something like her current profile photo where a robot arm pours coffee for her. For a prompt with this many elements, DALL-E generally gets all the elements into the scene, but often randomly mixes-and-matches concepts: making the woman into a robot or a woman with robot arms; having her pour the coffee; putting two coffee cups in her hands; giving her three arms; and so on. In addition, it struggles with fingers and faces in more complex compositions, similar to the indeterminate results common in GANs.

I tried a variety of visual styles, both because OpenAI disallows sharing realistic images with faces, and to avoid DALL-E’s struggles with realism on such complex prompts. But changing the artist changes the content, in ways that are often delightful but frustrate precise control. Using Norman Rockwell or Rowena Morrill made the clothing, robot, and setting old-fashioned; using Syd Mead produced sexualized images. We spent a lot of time poring over many different results and trying different visual styles.

Like a lot of creative processes, it might sound tedious but is actually really addictive and fun. I sometimes have trouble tearing myself away from using DALL-E.

After considerable trial-and-error, we found some prompts that worked well, such as:

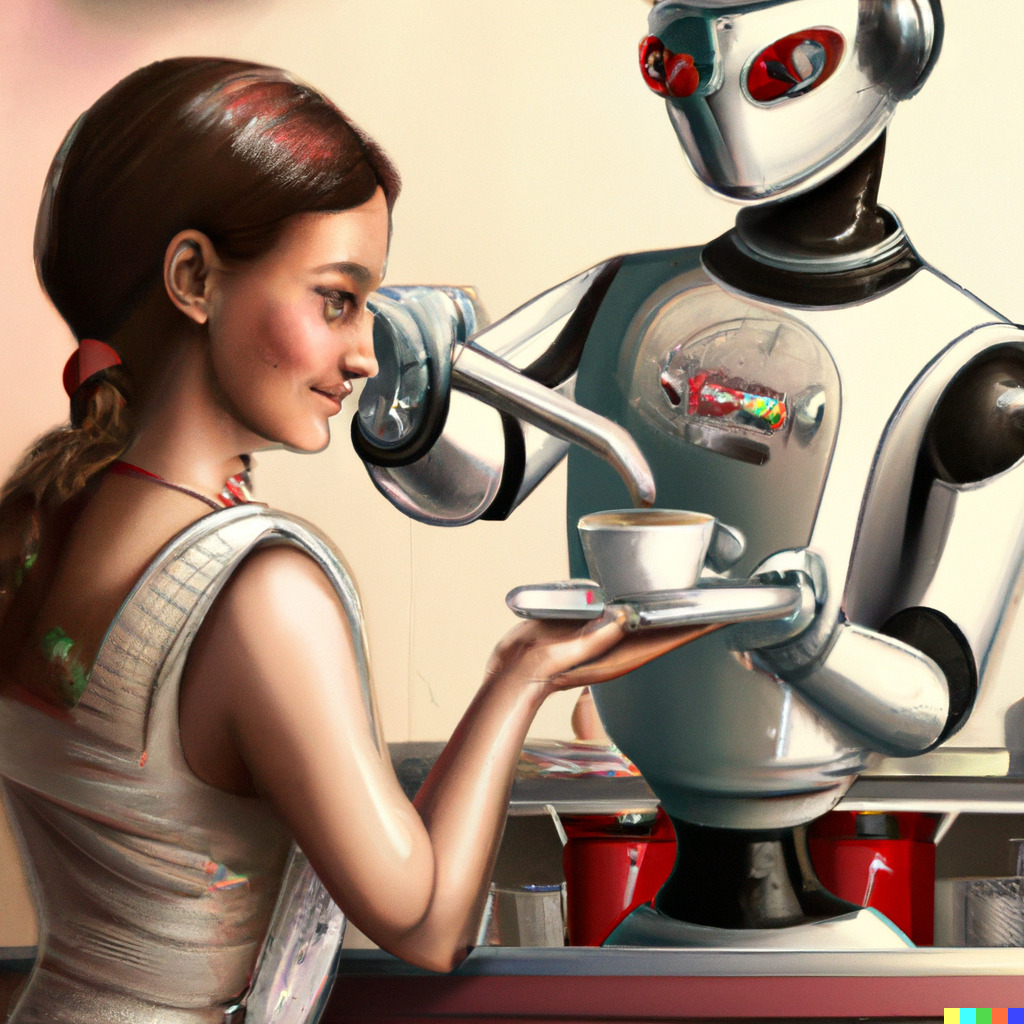

which includes a few good outputs, like:

One can edit the image further using the inpainting interface; I was able to fix the badly-poured coffee in one example this way. If desired, one could also touch up the details in Photoshop to improve it even further.

It’s staggering that an algorithm can do this. Each set of ten images takes less than a minute to generate. Even having to sift through all these outputs, there’s no existing way to pump out so many great results so quickly—not even by hiring an artist.

You can see more examples of this process in the comment threads on this Facebook post, and be sure to read the text prompts in the screenshots.

Also, I think this experience has taught me that “detailed realistic painting” is a good style to start with, which should make future explorations go a lot faster.

The forecast

For many applied tasks, like professional graphic design and illustration, you need a lot of control that DALL-E doesn’t provide. The initial GANs didn’t have them either, but lots of research followed the initial GAN papers to add many kinds of control and interaction. We will surely see many new papers coming that add those kinds of controls to diffusion models (like DALL-E) in the next few years.

How well could you use DALL-E for image editing? Based on the fiddly behavior of inpainting, which sometimes works great, and but often fails entirely, I would guess it’s not very reliable. (It’s hard to say since the inpainting algorithm hasn’t been disclosed.) Which suggests that it’s not going to be reliable for many image manipulation tasks if it can’t represent arbitrary images well in the model.

The underlying technology is going to keep improving; this week, Google announced Imagen, a parallel effort using similar technology that appears to have better results for photorealistic images. They say they have better ethical practices that, sadly, mean it might be less artistically interesting. As part of their ethical stance, they’re not releasing a public demo at all.

I’ve also heard from a few places that Imagen is more literal, predictable, and accurate, possibly due in part to the guidance weighting, and so might be better for more focused tasks, whereas DALL-E seems at first glance like a better creativity tool. But I also believe that any exciting new generative AI tool is going to enable some new forms of creativity.

Our children will grow up taking for granted that computers can “simply” produce realistic images, entire stories, or chat with them naturally, while we think that it is magic.

— hardmaru (@hardmaru) May 22, 2022

Just like how our previous generations thought the radio, telephone, TV, video calls seem like magic. pic.twitter.com/5tazufFWsC

Is it possible that, some day, these algorithms will really be able to capture all the visual concepts we care about? To paraphase Douglas Adams, the space of visual concepts is big. I mean, really big.

How does it work?

There’s a lot of mystique around AI software. But, as the first author of DALL-E says, the method is quite conceptually simple; it’s basically a statistical sampling algorithm. Philosophically, it’s the kind of curve-fitting and model sampling that one might learn in a Statistics 101 class. Google’s new Imagen uses similar techniques to DALL-E 2, and they also describe their method as “conceptually simple and easy to train.” In both methods, the results are astoundingly good.

That said, the specifics are only “simple” if you are up-to-date with the latest developments in neural image generation: while these methods are just data fitting, they’re data fitting in high-dimensional spaces that’s turbocharged with tasteful choices of modern algorithms, tons of model parameters, unfathomably-large datasets, careful engineering, and staggering computation times.

Personally, I think we would be better off if we could avoid using the harmful term “Artificial Intelligence” to describe these systems at all. It’s all just software that people wrote.

Is it creative?

The DALL-E announcement vexed me a bit because it came out just as I putting the finishing touches on a paper on computational creativity—DALL-E seemed to make some points in my paper obsolete before it was even published. For example, in the paper, I point out that existing stroke-based painting algorithms have fixed painting styles, which is still technically true but now irrelevant.

I had a moment early on while using DALL-E to generate different kinds of paintings, like “odilon redon painting of seattle”:

in which I thought, considering all the different painting styles I’d generated, (a) this is better than any painting algorithm I’ve ever developed, and (b) it’s a better painter than I am.

in which I thought, considering all the different painting styles I’d generated, (a) this is better than any painting algorithm I’ve ever developed, and (b) it’s a better painter than I am.

In fact, no human can do what DALL-E does: create such a high-quality, varied range of images in mere seconds. If someone told that you a person made all these images, of course you’d say they were creative.

But I still maintain that this does not make DALL-E an artist. In the computational creativity community, some people have argued that computers could be considered creative, and that we can judge their creativity according to the novelty and quality of their outputs. By those measures, DALL-E has already surpassed humans. But, as I’ve argued before, we’ve already got algorithms that produce high-quality, novel outputs; we can’t judge creativity just by the outputs, though surely there are elements of human creativity here. The difference is that DALL-E can produce much more variety and sustain interest for much longer than previous methods.

Creative processes as exploration

In the new paper I mentioned, I point out a missing element in a lot of popular and academic conceptions of creativity: the role of open-ended exploration.

We often discuss artworks and inventions as though they result from the artist or inventor’s goal or intent. The artist intended to show a thing, or express an emotion, and so they made this image. But, when I began painting again a few years ago, I found that my paintings came from the process, not just my goals. And, when I started to look around, I found numerous examples of artists and researchers describing their own processes in the same terms. The paper provides many examples and quotes from artists about how art and creativity isn’t necessarily about intent.

One example is this clip of Paul McCartney coming up with “Get Back” in a jam session. He didn’t start with an idea of what the song was about, or an intention for the meaning of the song; he just started jamming and the band developed it from there.

For me, comments, ideas, collaboration, and “Likes” from other people also provide necessary fuel for the creative fire.

Finding my “style”

In my own explorations with DALL-E, one idea would lead to another which led to another, and eventually I’d find myself in a completely unexpected, magical new terrain, very far from where I’d started. Stanley and Lehman describe discovery and creativity as a sequence of stepping stones, an apt analogy for this process.

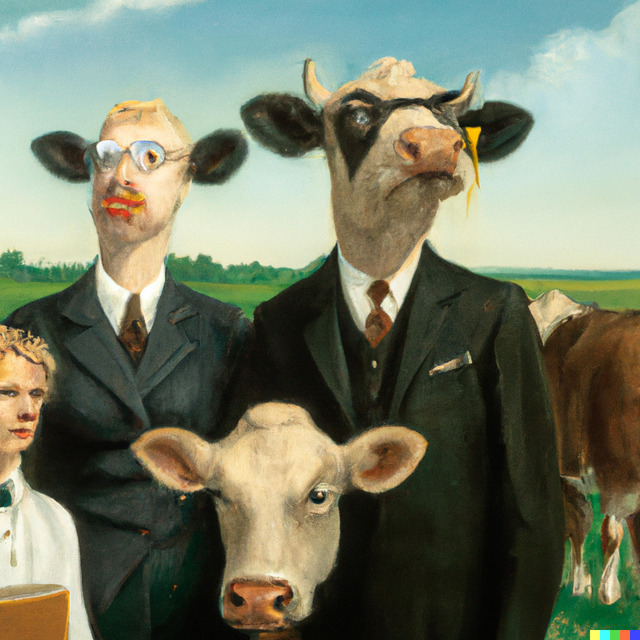

As one does with a new tool, I started playing around: generating zany prompts, probing and testing the system, and spending hours with friends coming up with new prompts and riffing off each others’ ideas, like this “Norman Rockwell portrait of a family of business cows”:

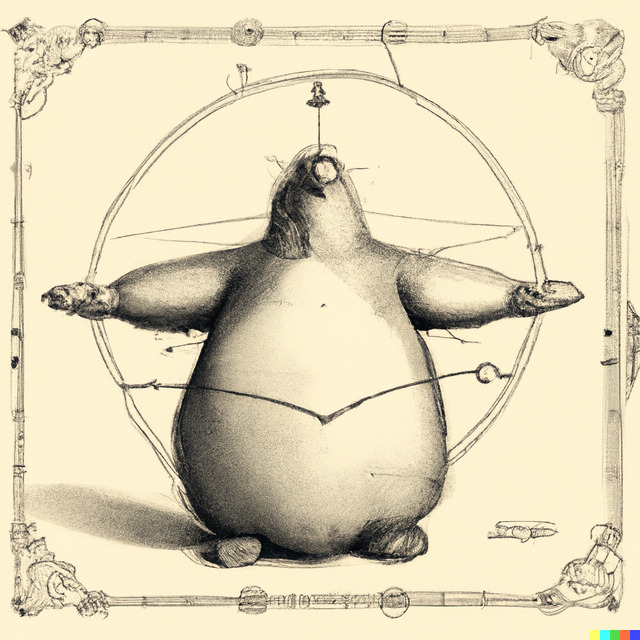

And, “The Vitruvian Manatee by Leonardo da Vinci”:

Something that week had made me think of the contemporary painter Sarah Morris; I wondered if DALL-E knew her style, and it did. So I figured I could try more contemporary and modern artists beyond the usual suspects. I think I liked the Jeff Koons images more than I like actual Jeff Koons artworks, and I loved what it did with artists like Kehinde Wiley and Maurizio Cattelan. After running enough of these experiments, I put these images into a single thread on social media, while wondering how pleased and horrified these artists would be if they ever saw this.

Here’s a “Sol LeWitt painting of an oscilloscope”, made because Sol LeWitt is an important precursor to the history of generative art:

I began to see my experiments as “series,” like artists’ series: a consistent dive into a single theme, rather than a set of independent wacky images. Other people can make better, more-viral images than me. I like to think I have a bit of a subtler artistic style with these images; some of the images are like the things I like to paint, and maybe the style is close to my taste in art, since so much of making art with DALL-E is curating results.

Ideas for these images and series came from all around, often linked in a series of stepping stones. One of the final ideas in that first series was a Yayoi Kusama installation, and, after trying a few unsatisfactory locations for it, I hit on the idea of placing it in La Mezquita, in Córdoba, Spain. I sent the picture to an architect colleague, Manuel Ladron de Guevara, who is from Córdoba, and we began riffing on other architectural ideas together. This became a series on buildings in different architects’ styles.

A drive up the California coast led to the idea for my next series: classic computer graphics images. (I thought the “buzz and woody, 3d render” was pretty funny.) Comments on the Facebook page for that series led to the next series: portraits of friends and colleagues. Here are two portraits that came directly from the prompt each person provided, without iteration:

The “robot pouring coffee for a woman” also came from this series of portraits.

Prompting as art

I’ve started to consider what I do with DALL-E to be both an exploration, and a form of art, even if it’s amateur art like the drawings I make on my iPad. In this, I am influenced by artists like Ryan Murdoch and Helena Sarin who have advocated for this kind of prompt-based image-making to be recognized as art.

Working with DALL-E, or any of the text-to-image systems, means learning its quirks, developing strategies for avoiding common pitfalls, knowing about its potential harms (some are quite hidden) and surprising correlations, like the way everything becomes old-timey when you select an old painter or photographer’s style.

Meeting very specific, concrete goals is often frustrating, as illustrated by some of the examples above. Sometimes I can find a good image, especially if my goals are vague, but always the process will be delightful, and offer up surprises that lead to new ideas that themselves lead to more ideas and more and more.

It’s too early to judge the significance of this art form. A phrase from the excellent book Art in the After-Culture keeps sticking in my head: “The dominant AI aesthetic is novelty.” Surely this would be true, to some extent, for any new technology used for art. The first films by the Lumière brothers were novelties, not cinematic masterpieces; it was amazing to see images moving at all. (That quote comes from a chapter critiquing the way AI art benefits big technology companies.)

But AI art software develops so fast that we’re in a cycle of continual technical, artistic novelty, and it seems each year we’re exploring an exciting new technology, more powerful than the last.