The Curse of Performative User Studies

Why user studies in graphics and vision are (probably) often wrong, and what we can do about it.

This essay has been published here:

- A. Hertzmann, “The Curse of Performative User Studies” in IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications, vol. 43, no. 06, pp. 112-116, 2023. Official Link

Anyone who has spent enough time publishing some kind of artistic tools in computer graphics—even in computer vision conferences—has probably gotten reviews that praised a paper’s ideas and results, but required a user study. Or the reviewers didn’t like the paper’s methods or results, but still said the authors should add a user study. And so, maybe you added user studies to your next paper solely because you believed reviewers would require it.

Studies with human subjects—today grouped under the term “user studies,” even when they don’t involve target users—provide invaluable insights about user preferences and behavior, sometimes pointing out new research directions. Some subfields, including animation and tone-mapping, have long traditions of rigorous perceptual and psychophysical studies. But, performing an effective study requires time, effort, and thought.

Instead, many of our user studies are conducted sloppily, as an afterthought to research, rather than part of the research itself. Such perfunctory studies have proliferated since 2008, after the introduction of crowdworking using Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) made it easy to gather numerical scores from human participants.

Reviewers expect user studies particularly for tasks that resist easy benchmarking, including artistic stylization and interactive authoring tools. Since stylization and neural image synthesis became mainstream topics in computer vision conferences, reviewers at these conferences increasingly ask for user studies. Yet, few standards—if any—seem to govern how the studies are conducted.

I argue that many studies now published in graphics and vision are performative, not informative: we do them not because we want to learn something, but solely because reviewers expect to see a table of numbers. So we put on a performance, a bit of science theatre.

The desire for user studies reflects a deep question: how do we know if a paper’s method is any good? This difficult question defies any easy answers. But, many researchers I’ve talked to seem to believe that quantitative evaluation solves the problem. And so, it becomes required. How could you publish without a table of numbers? Yet, too often, the numbers produced by sloppy user studies seem unnecessary and unhelpful, just a waste of everyone’s precious time.

The field of HCI has grappled with these same issues since long before MTurk existed, and has concluded that user studies are only sometimes—not always—necessary for evaluation. For example, take a look at what this year’s UIST 2023 Author Guide says about them (under “User Studies Are Not Required” and “Systems Contributions Need To Be Evaluated Holistically”). We can learn from the experience of HCI.

We need a better understanding of if, when, and how user studies are valuable, and we need to adjust reviewing practices accordingly. In this piece, I’ll discuss the problem and provide some recommendations for what we can do about it.

An example of bad reviews

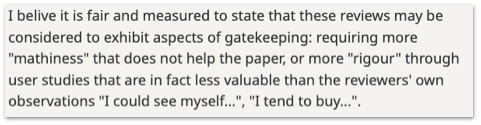

While not a graphics paper, a recent paper called “EinOps” offers an instructive example with publicly-visible reviews. Two of the reviewers argued for rejection, saying that, while they believed in the technique’s value, nonetheless the paper must support its assertions with user studies. In the rebuttal, the author added a user study. But, in the decision, the Area Chair (AC) scolded those reviewers:

To this anonymous Area Chair, I say “Bravo.”

If this sounds weird, I recommend reading the Paper Decision and reviews and then thinking through what user studies the authors could have actually performed, and whether they would have been genuinely meaningful or necessary. Would the author—who does not appear to be academically-employed—have had the time, energy, and expertise? Moreover, this Area Chair had outside knowledge of the system’s impact—would they have rescued the paper otherwise?

In computer graphics and vision, I’ve seen so many similar examples of reviewers offhandedly writing “you should have a user study” without any apparent thought to the consequences, or to what genuine value such a study would add. Reviewers ask for studies not because they need information, but because “papers should have evaluation.” I’ve also heard of a few cases where reviewers demanded evaluations with real deployments and real users that would have required multimillion dollar product developments. It did not seem that the reviewers had really thought critically about what they were asking for.

It’s also sad to see authors diligently add user studies at the reviewers’ request, only to have a paper keep getting rejected anyway. Like the EinOps reviewers, some reviewers seem to write “lack of user studies” as a scientific veneer for their real judgments. That is, rather being honest and saying “I’m not very impressed with the submission” or even “I’m just not sure,” it’s easier to say “there’s no user study.”

In the case of EinOps, instead of asking for user studies to support claims about user behavior and preferences, the reviewers could have instead asked the author to rephrase the claims, e.g., to reflect personal experience and observations.

Some user evaluation requests are even more ridiculous. One colleague at Pixar complained that reviewers rejected his paper because he’d not had animators make a professional animation with the system—essentially, the reviewers were asking for a multimillion dollar production. Even in the CHI community people complain about evaluation requests that would require years of extra effort. It’s unclear that reviewers have really thought through the effect of what they’re asking for.

Pitfalls

When performed well, a user study provides new information and answers questions about user preferences or behaviors. But, poorly-performed user studies can also be harmful, in ways that I summarize in this section. And, even studies that are merely useless cost researchers, reviewers, and readers valuable time, while perpetuating a culture of useless studies.

The Redundancy Pitfall

Often the ideas and the results in the paper figures are convincing enough to justify publication, and so a user study is redundant. If the ideas and the figures provide reviewers enough reason to believe in the paper, then no study should be necessary. In these cases, I doubt the reviewers pay much attention to the contents of the study anyway, only checking that it exists.

Quantitative user studies used to be rare in graphics, almost unheard of before 2009. Yet, there were lots of good papers anyway. In the two volumes of Seminal Graphics Papers, which collect 138 of the most important papers in the history of computer graphics, only two of the papers have anything resembling a formal user study (“Where Do People Draw Lines?” and “Scene Completion Using Millions of Photographs.”).

User studies can play a valuable role, providing a “sanity check,” when there’s a serious question of whether the results are representative or “cherry-picked.” How does the method generalize? But this sanity check isn’t always necessary, and it must be performed carefully, if done at all.

The Replicability Pitfall

It may be that a paper’s method isn’t very good, but the user study seems to show that it is. There are lots of ways to produce such a study.

In one recent project, my collaborators and I ran studies with several different crowdworking methods common in graphics and vision, and we found that different studies gave opposite conclusions. Our paper reports on all the experiments, and what we learned from them. However, we could have simply reported only the results that supported our research goals, making our story much simpler and more compelling—but also misleading.

I wonder how many published “user studies” in graphics and vision were performed this way: keep running MTurk evaluations until you get the result you want, only publish that final evaluation, and then declare victory.

In an influential 2011 psychology paper, Simmons et al. detailed many ways that experimenters can bias results towards the results they want, even unconsciously—including publishing only the studies that support the hypothesis and discarding the rest. Observations like this led to the Replication Crisis, in which psychology researchers found that that many published studies could not be replicated in independent trials, thus invalidating large swaths of recent scientific research. The crisis led to widespread reforms in psychology and other fields, including the use of preregistered studies and new policies on reporting experiments. We should learn from this experience, especially since many of our user study methodologies are variants of psychology methodologies.

If rigorous scientific experiments have gone through such an upheaval, shouldn’t we wonder about some of our own experiements? Indeed, there have been related concerns raised of a replication crisis in computer science and in machine learning, as well as evidence that dataset bias leads to results that do not generalize well. (Note that the easily-confused terms “reproducibility” and “replicability” are sometimes swapped in their meanings. I’m skipping over the precise meanings here.)

Closer to home, Natural Language Processing (NLP) research employs human evaluation of results similar to how we use them in graphics. But, a recent series of studies finds that most evaluations in NLP research are woefully non-replicable, with serious questions about whether the evaluations are at all meaningful. I’m not aware of any such study in the graphics literature.

All of the above leads me to hypothesize that many quantitative user studies in computer graphics and vision would not hold up in new experiments, due to a lack of experimental rigor.

The Hard-To-Quantify Pitfall

Many kinds of research are fundamentally difficult to quantitatively evaluate, and honest authors may struggle to do so, being unwilling to put together a useless user study. Their papers then get rejected when reviewers insist on bogus user studies. This causes considerable frustration, sometimes leading authors to avoid entire subfields of research as a result.

Could MTurk Lose Its Value?

If that’s not concerning enough, consider this. Crowdworking on MTurk grew popular for user studies after a series of studies in HCI, visualization, and psychology showed that crowdworking gave similar outcomes to in-person studies. But, there’s some evidence that the reliability of MTurk data has gone down over the years.

What’s more, there’s some evidence that MTurkers are starting to use LLMs to generate answers to their survey questions. I’ve already heard anecdotally of MTurk survey responses that begin with “As an AI Language Model”, indicating that this is already happening.

MTurk might not be useful for much longer.

Common Responses

Over the years, myself and others have raised some of these issues before in various forums. I believe the common responses are telling.

Some people respond with: “But then how do we evaluate papers?” How best to perform evaluation is an important question. But the question presumes that quantitative evaluation is necessary for publication—and that the current measurements are better than nothing, even when they’re meaningless.

Certainly, when we have reliable ways to evaluate our work quantitatively, we should use them. But we should also recognize the shortcomings of our metrics, and adapt. Otherwise we fall into the McNamara Fallacy, named for former US Secretary of State Robert McNamara. This fallacy entails making decisions solely based on whatever we can measure numerically, and treating all other considerations as though they don’t exist, even though they may, in reality, be more important than what’s measurable.

The other response seems to be apathy: our field doesn’t seem particularly concerned about whether or not our studies are “true.”” This again raises the question of why we are doing them at all. If we’re doing them, we should care about whether or not they’re meaningful.

What Should We Do About It?

There are a few things we can do about these problems, both individually and as a field.

Stop requiring useless user studies “You should do a user study” should be treated like “This method is not novel”: You shouldn’t say either without explanation.

A reviewer requesting a user study should precisely specify the purpose of the study and how it would be conducted. Reviewers should think through what evaluation should be performed, and how the results of it might change their evaluation of the paper. The goal can’t just be “to see which method is better,” because no study can answer such a generic question. Even with a well-defined task, a technique may work well for one class of problems or users, and poorly for another.

Likewise, authors, committee members, and paper chairs should push back on reviewers that ask for user studies.

Conversely, be open to qualitative user studies that can provide information that quantitative studies lack.

Conduct user studies thoughtfully, but sparingly. We should do fewer user studies, but better user studies. User studies should be performed carefully, with the aim of gathering specific information or answering a focused question, and carefully reporting the results. Think carefully about what questions you can address and what information a study provides. Incorporating user feedback early in the research can be particularly valuable.

Moreover, there are many different kinds of user studies and user research besides quantitative MTurk evaluations. Informal, qualitative user feedback can provide a lightweight indication about the usefulness of a system.

We can look to various evaluation techniques developed in HCI, including those summarized by Ledo et al.. Their “demonstrations” category roughly matches our common practices of showing results figures, but they offer specific guidelines about these demonstrations. They also discuss different ways that usability can be evaluated, beyond just quantitative scoring of responses.

See our recent survey paper for more advice.

Accept that reviewing is a judgement call. Many of these problems stem from a quixotic desire for scientific objectivity in research. We must accept the fact that paper decisions are subjective and involve judgement calls. In many top computer science conferences, we accept papers based on whether we think the paper will make a positive impact. This is why we reject many papers for no particular flaw other than not being very “novel” or “interesting.”

We also need to recognize that almost no graphics paper evaluates with real applications in real deployments. All our datasets and benchmarks are approximations to what a real practitioner might care about, and sometimes they are poor approximations. Indeed, the “users” in our so-called “user studies” are almost never actual users of the proposed system.

Hence, reviewers must make judgement calls about whether the ideas and results are valid, interesting, and worth publishing. User studies can help with these judgments if done well.

Discourage bad studies. Poorly-done studies make a paper worse, and they perpetuate expectations that papers include studies, even bad ones. But, at present, authors are incentivized to include them, just in case they get that reviewer or committee member who uncritically demands a study. Ideally, when reviewers or committee members identify bad studies, they should explain the issues to authors and require them to remove the bad studies, even for papers being accepted for publication.

Do new research on user studies. I wish I had precise instructions for exactly how to do evaluation, apart from ``use good judgment (and read our survey).’’ But I don’t think there’s an easy recipe.

Many fields, when confronted with an evaluation problem, have developed new methodologies and approaches to evaluation. It seems most field need to occasionally revise their standards for evaluation. In computer vision, benchmark datasets addressed the widespread problem of not being able to tell whether new methods were any better than the old ones. This led to a long period of extraordinary progress, but now over-reliance on benchmarks and quantitative evaluation cause their own problems. In Psychology, the Replication Crisis included research describing the problem, studying its extent, and developing new guideliness addressing it.

Here are some research questions—specific to graphics evaluations—that we may wish to ask. Do readers’ evaluations from the paper figures predict the results of user studies? That is, when do studies provide more information not available from paper figures? Do existing studies hold up to replication? Such methodological tests could be performed in some artistic domains like image stylization or character animation, comparing across many published methods, and comparing with non-crowdworked assessments, made by actual expert users of such software, in multiple target domains. What factors affect the usefulness of studies? Some of these will necessarily be specific to subfields, e.g., how rendering style affects judgements of character animations. Some judgments will be more robust than others, e.g., judgement of image restoration quality may be much more consistent than aesthetic preferences for indeterminate images.

Develop new guidelines. With sufficient research on user studies, conference chairs could adopt guidelines around how to perform and report studies. Other fields have done so, for example, as a result of the Replication Crisis, many psychology journals adopted new standards for performing and reporting psychology experiences.

Particularly noteworthy for us is HCI’s response to years of discussion about user studies. The UIST 2023 Author Guide explicitly states: “User Studies Are Not Required … rather, papers must support the claims they make with evidence. The form of that evidence will vary based on the claims of the paper,” and then provides a nuanced discussion of the different issues and approaches around evaluation, while asking reviewers to familiarize themselves with papers that discuss these issues.

We could have the same thoughtful and evidence-based approach to user evaluation in our fields, if we so chose.

Further reading

In-depth discussion of user studies in graphics and vision, how to improve them, and use other techniques for user research:

- Zoya Bylinskii, Laura Herman, Aaron Hertzmann, Stefanie Hutka, Yile Zhang. Towards Better User Studies in Computer Graphics and Vision. Foundations and Trends in Computer Graphics and Vision, 2023. Vol. 15: No. 3, pp 201-252. Official Link

An influential, eye-opening survey on the ways that researchers can cheat when doing studies, even unintentionally:

- Joseph P. Simmons, Leif D. Nelson, Uri Simonsohn. False-Positive Psychology: Undisclosed Flexibility in Data Collection and Analysis Allows Presenting Anything as Significant. Psychological Science, 2011.

How working with real users can inform and drive good research in computer graphics:

- Maneesh Agrawala, Wilmot Li, Floraine Berthouzoz. Design Principles for Visual Communication. Communications of the ACM, April 2011, 54 (4), pp. 60-69.

An insightful HCI paper pointed out many of these issues 15 years ago:

- Saul Greenberg, Bill Buxton. Usability Evaluation Considered Harmful (Some of the Time). CHI 2008.

How the UIST program committee deals with this issue:

- UIST 2023 Author Guide, scroll down to “User Studies Are Not Required” and “Systems Contributions Need To Be Evaluated Holistically”.

These ideas benefitted from discussions and collaborations with many people, including Maneesh Agrawala, Zoya Bylinskii, Stephen DiVerdi, Andrew Fitzgibbon, Perttu Hämäläinen, Laura Herman, Cuong Nguyen, plus countless reviewers that asked me and other authors for user studies.