Why DeepDream Dreams of Doggies

The DeepDream algorithm creates hallucinatory imagery, fantasizing elements of architecture and animals from input images. The algorithm made a big Internet splash when it came out in 2015. An algorithm meant to provide a relatively ordinary visualization task produced wild imagery that some people compared to LSD trips and perceived as “creativity in the mind of the machine”.

DeepDream was, arguably, a novelty. However, it was one of a few algorithms that launched new interest in AI algorithms for art, around which a new community has grown, and continues to grow.

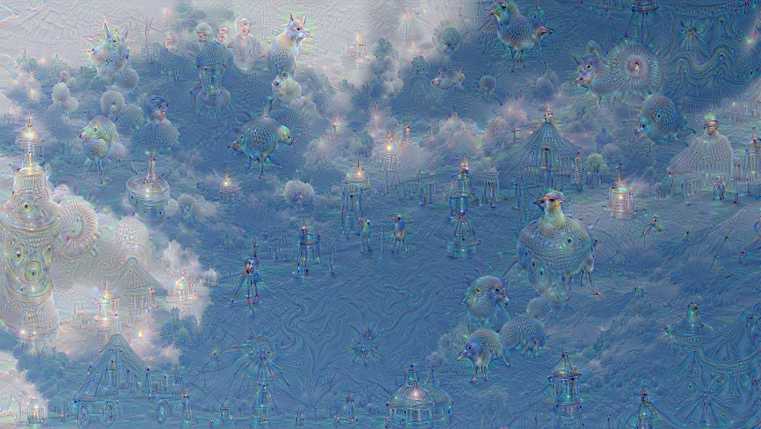

Here’s one of the first images from the original description of DeepDream:

and some of the structures they found:

These structures resemble creatures, often some sort of dogs. And, the more images people produced using higher-level network layers, the more dogs appeared.

Why dogs?

It turns out that DeepDream’s obsession with dogs isn’t because they’re cute; it’s an accidental by-product of history. Specifically, as pointed out by an ImageNet coauthor, it’s because there are a lot of dogs in the dataset. It’s worth understanding why. There’s new attention recently to analyzing the contents and structures of datasets. DeepDream doggies present a small-but-interesting case study in the unexpected effects of a seemingly-minor technical choice made long ago.

Maybe our current era of AI art wouldn’t have taken off in the same way, were it not for this one little choice made years ago.

Toward Fine-Grained Classification

The ImageNet dataset was developed over several years in Fei-Fei Li’s lab, with the aim of creating the first very large dataset for computer vision. In the initial publication in 2009, it comprised a large collection of images scraped from the web and loosely labeled by human annotators. However, these crowdworker annotations were not very good, or very meaningful.

In order to get better annotations, the researchers, led by Jia Deng, devised a more rigorous annotation methodology. But this methodology was more expensive and time-consuming, so they had to narrow it down to a challenge subset of 1000 categories. What should those categories be?

These 1000 categories were chosen to test different aspects of a vision system’s performance. On one hand, most of the categories were aimed at testing coarse image classifications, e.g., being able to distinguish lobsters from teakettles. But vision isn’t just coarse image categorization. They also wanted to test fine-grained categorization within some class of objects. What should the fine-grained categories be? Previous fine-grained datasets had been based on object categories like birds and clothing style.

For whatever reason, they chose dogs. Starting with the 2012 version of the challenge dataset, they included many different dog breeds, since distinguishing a miniature schnauzer from a dalmation is a very different problem from distinguishing a lobster from a teakettle.

As a result, dogs represent a whopping 12% of the challenge dataset. The challenge, known as ILSVRC2014, was won by a network called Inception. And then other researchers began to work on visualizing how Inception works.

Cry “DeepDream,” and Let Slip The Dogs of ImageNet

DeepDream, created by Mordvintsev et al., began as a visualization technique, creating images likely to “excite” intermediate neurons. That is, it seeks to answer the question: what kind of images “excite” the Inception network the most?

The answer is, to a large extent, images with dogs. If, over your entire life, you saw dogs 12% of the time when you’re eyes were open, you’d have dogs on the brain too. As pointed out by one of the ILSVRC coauthors, DeepDream makes dogs because it’s seen them so often.

DeepDream also makes creatures, buildings, and vehicles. And, indeed, looking through the categories in ILSVRC2014, many of the categories are creatures, buildings, and vehicles. There are also numerous household object categories, but these don’t appear as much in DeepDream, perhaps because they are more visually dissimilar to each other. That is, all birds have eyes and beaks, but “soccer ball,” “saxophone,” and “umbrella” don’t have much in common visually. Notably, there very few people in DeepDream; ILSVRC2014 only includes three person categories (and one of them is “scuba diver”), though people may appear in other images in the dataset.

Although generative art and AI art have been around for nearly six decades, DeepDream helped popularize it for a new generation. Artists began to explore DeepDream, a first step toward “AI artist” being a category in itself today.

DeepDream wasn’t the first algorithm to create this kind of feature map visualization, but it was the first to become Internet famous. Would DeepDream have been so popular without the dogs and other creatures?

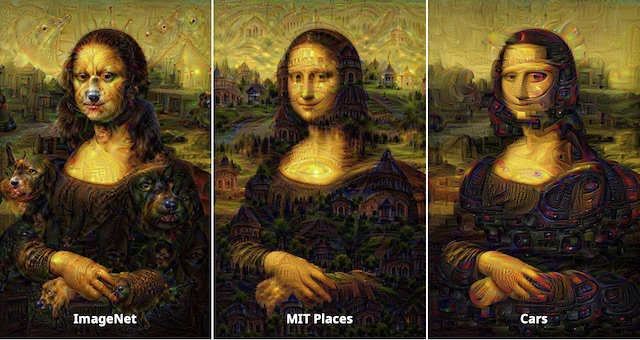

Here are some later images, computed using DeepDream with networks trained on other categories (places and cars), taken from this website:

In the conventional DeepDream, evocative doggies appear, whereas the structures in the other images, while interesting, don’t have the same power.

If, years earlier, the ILSVRC creators had instead focused on fine-grained categorization of cars or places, and DeepDream only made mutant cars or buildings, then perhaps it would not have excited imaginations quite the way it did, or helped launch an AI art movement the way that it did.

Thanks to Alex Berg for reading an early draft of this.