Apparent Ridges, Edges, and Perception of Line Drawing

Note: a revised and updated version of this post has been published in Perception, or see the preprint: http://arxiv.org/abs/2101.09376.

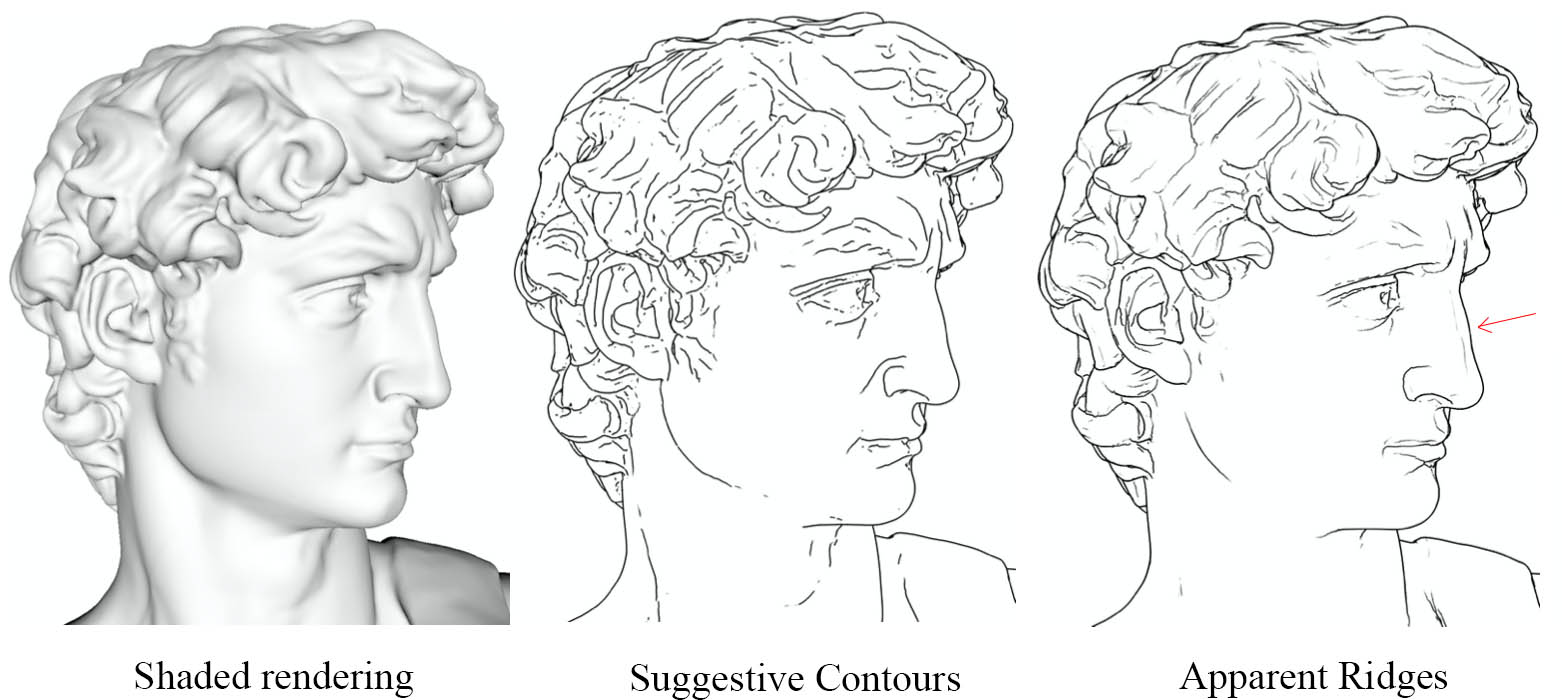

Two of the most compelling algorithms for describing how humans create line drawings of 3D models are the Suggestive Contours and the Apparent Ridges. In a recent article, I provided an explanation for human perception of drawing in terms of Suggestive Contours. However, in the best quantative study on where people draw lines, Apparent Ridges got better scores.

This essay attempts to resolve this apparent contradiction, and explain the role of each in understanding line drawing. I spent a lot of time thinking about this when preparing my article, but decided to omit this discussion for the sake of brevity.

What are the models?

The Suggestive Contours algorithm draws lines at dark valleys of a particular image rendering. The Apparent Ridges algorithm draws lines at large gradients of a particular rendering. Both produce high quality line drawings in different cases, and there are several published variants to these algorithms.

I won’t go into much detail here about how these algorithms specifically work. You can find a non-technical introduction to line drawing algorithms starting here. For more detail, I recommend the original papers, which are very well written, as well as the method of Lee et al.; see the survey by DeCarlo for a comprehensive view of these algorithm. Incidentally, Pearson and Robinson basically proposed Suggestive Contours in 1985, but didn’t develop any algorithms for 3D models.

What do the studies say?

First, what do the quantitative evaluations actually say?

I know of three studies that are relevant here; each of them evaluates something different. First, Cole et al asked human artists to create line drawings from 3D models. The authors found that methods related to image edges and image gradients—including Apparent Ridges—were the best predictors of hand-drawn lines. However, there were shapes where Suggestive Contours performed better. Second, in a separate study on how people perceive shape from line drawings, Cole et al. found that people perceive shape with roughly-equivalent accuracy from Suggestive Contours and Apparent Ridges (see Table 1 in their paper). Apparent Ridges did slightly better on models with a lot of creases (especially “bumps”), and Suggestive Contours did a bit better on some other models. Finally, in our Neural Contours paper, we also found that image edges and Apparent Ridges best matched human judgements of how good line drawings looked.

As useful as these studies are—the two by Cole are especially important and significant—there are a number of reasons to question any specific conclusions about ARs and SCs. These studies studies are generally comparing these curves in isolation, but one gets better scores by combining different kinds of curves. I also think that the evaluation of these methods is a little iffy for mechanical objects with creases. I think one reason Apparent Ridges scores well is that it essentially subsumes creases, whereas Suggestive Contours needs to be combined with creases, and combining multiple curve formulations causes issues that haven’t been addressed yet by current algorithms. On the other hand, Apparent Ridges (as currently formulated) can’t create junctions, e.g., where 3 creases come together, and cases like this are not penalized much by current evaluation metrics. Moreover, each of these is just one study in a particular test setup and sample set.

In short, there are cases where Apparent Ridges gets higher scores on some tasks, but there is no clear “winner” or answer to any question about which method is “best.” There is a need for more research to improve and extend these algorithms, and perhaps also to develop more perceptually-valid metrics for evaluating them.

Apparent Ridges in the Realism Hypothesis

Apparent Ridges is based on the idea that line drawings follow image gradients, which I do not believe is a good explanation for perception.

How do I reconcile my hypothesis that Suggestive Contours explain line drawing perception with the fact that Apparent Ridges seem to perform at least comparably well?

The key idea is that, in my hypothesis, even though a viewer perceives lines as if they are Suggestive Contours, the “best” line drawing of an object is not the Suggestive Contours drawing. (For the sake of this discussion, I will assume smooth surfaces and assume occluding contours are always drawn.)

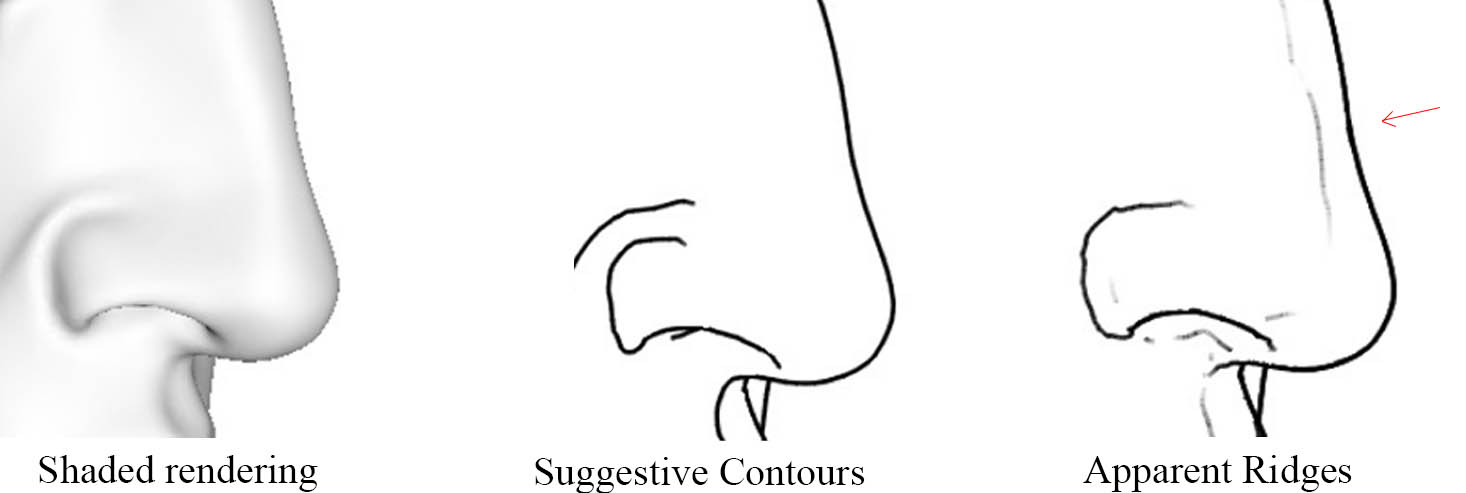

Consider this “nose ridge” example (rendered by Pierre Bénard using qrtsc):

This is similar to Figures 3 and 9 in the Apparent Ridges paper; in Figure 3, the authors point out artworks that use similar ridges.

This is similar to Figures 3 and 9 in the Apparent Ridges paper; in Figure 3, the authors point out artworks that use similar ridges.

I interpret this line as exaggerating the curvature of the nose, in order to show that it’s not flat. The line indicates a sloping surface; it indicates a Suggestive Contour that isn’t “really there.” In my hypothesis, this means that I will perceive a 3D surface that is slanted more than the real surface. In contrast, this line is missing in the Suggestive Contour rendering; however, this makes the viewer perceive the surface as flatter. If the overly-slanted surface is a better reconstruction than the overly-flattened surface, then it makes sense to draw that extra curve.

More formally, suppose the vision system should infer a 3D shape that is consistent with the Suggestive Contour model: each line should either be an Occluding Contour, or a Suggestive Contour, and the vision system infers the most probable shape that fits these constraints (possibly with some perceptual uncertainty). If the artist’s goal is to minimize the distance between the perceived shape and the intended shape, then they draw lines that “aren’t there” in order to indicate high surface slant that might otherwise be perceived are more fronto-parallel.

To restate this as a concrete prediction: suppose you ran a shape estimation algorithm that inferred 3D shape from sketches, using the Occluding Contour + Suggestive Contour assumption (and creases were handled as well). Then I hypothesize that this algorithm would produce roughly equivalent renderings from each of these different line drawings, and that the drawing that led to the best shape reconstruction (e.g., minimum reconstruction error) would often not be a Suggestive Contour rendering. This is something that could be tested with the kinds of algorithms that we have available now.

Explaining variability and lines-as-edges

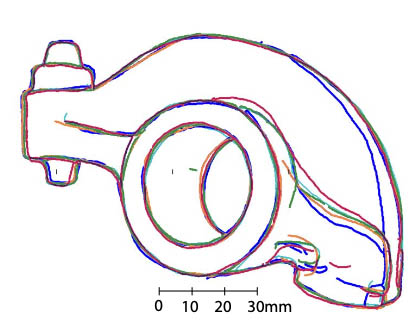

There are a lot of different drawings you can make that will lead to roughly the same percept. Here is a plot of the variability in human-made drawings, from Cole et al 2008:

Observe that everyone basically draws the Occluding Contours, but the interior curves are drawn in different ways. This may reflect the different skills and styles of the artists, but it may also reflect the fact that different curves will give roughly the same shape percept.

This gives a possible way to explain why line drawings occur so often at image edges. In the Realism Hypothesis, line drawing can conceptually be modeled as a process of creating a “virtual 3D scene,” with lighting, shading, and 3D shape, and then drawing lines that match this rendering. Since an artist has many choices for how to set up a “virtual renderer” when depicting an object, they can choose a virtual lighting and modified 3D shape that produces a set of lines that mostly align to the edges of a realistic rendering. Even if image edges do not explain human line drawing perception, they might be often the best places to draw lines.