Photography is not Objective, Art is a Set of Choices

Note: a version of these ideas now appear in a paper in Journal of Vision.

“You don’t take a photograph, you make it” —Ansel Adams

“Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.” —Edgar Degas

Over the years, I’ve heard—and believed—many variants of the ideas that photographs directly portray reality, and painting depicts the artist’s reality. People treat photographs as though they are just like seeing the real thing—as long as there was #nofilter. I’ve been told that my paintings show how I see the world. I’ve heard these kinds of things both in casual conversation, and also read them in scholarly texts in psychology, philosophy, and art. For example, some researchers claim that Van Gogh painted with a yellow tint or nonlinear perspective because he saw the world differently.

These ideas can be summarized as: an artwork displays the artist’s perceptions and experiences, and that photography records and displays objective information. Photography, being made by a machine, records objective informations whereas artists record subjective information. While many authors have pointed out problems with these ideas, they seem to nonetheless be widespread.

In this blog post, I argue that these views are wrong. Photography is not objective truth. Photography and painting both result from deliberate choices of depiction, and there is no dividing line between them.

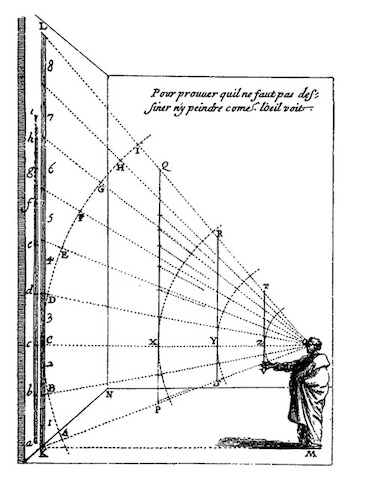

In two previous posts, I wrote about perspective and tonal choices in representational pictures, whether in photography or painting. These choices determine what a picture looks like, and, largely, how people interpret it. Even though photography arises from mechanically recording light, artistic and technical choices determine how recorded of light gets displayed. Different choices lead to different photographs or paintings, which give a viewer different perceptions, and none is objectively “correct.” These same kinds of choices are made in each, even though the process for making these choices are different.

Pictures are like stories, told with light rather than words. Perception is interpretation, and visual art is a construction made for perception.

The Impossibility of Capturing Experience

It’s worth appreciating just how impossible it is to try to capture real visual experience with a photograph. For those of us with mostly-normal (corrected) vision, our two eyes receive light from a wide horizontal and visual field that doesn’t map onto a flat plane. Each eye sees a different part of the world, which our brains use to get a sense of shape. Different parts of the world are blurry or sharp as our eyes refocus. We can interpret light in a broad range of intensities, from dim nighttime indoors, to bright sunlight. At any instant, we perceive extremely fine details in one direction (the foveal direction), with much coarser information in peripheral vision.

Projecting all this information onto a low-resolution, flat, static, planar array of pixels or pigments naturally throws most of the information away. It only captures one tiny slice of the light in the world. No conventional photograph or painting can capture the full richness of what we experience at any given instantaneous moment of real life. And this is to say nothing of directly conveying concepts or emotions visually.

Hence, pictures cannot fully convey real experience. At most they can only represent aspects of it.

Choices, Choices

“It’s all a big game of construction—some with a brush—some with a shovel—some choose a pen.” —Jackson Pollock

Making a representational picture—whether a drawing, painting, or a photograph—requires making a whole lot of choices. Some of these choices we make consciously, some intuitively, and some may be entirely hidden.

Imagine you’re in a new place, whether a new city street or a new mountaintop. You see countless sights and sounds in every direction, and you want to make a picture. What picture do you make?

The first choices are: what to depict/photgraph? What is included and what is cropped out? These choices alone can dramatically alter the viewer’s understanding of the scene, as compared to what you experienced. A photograph of a set of protestors can be made to look like a big mob with zooming and cropping, even if zooming out shows them to be an isolated group barely noticeable in an otherwise empty setting.

But, even once we’ve pointed the camera in a specific direction and framed the shot, there are still many choices to make. In photography, tonal and color choices in consumer photography result from many hidden choices made by camera manufacturers, even if we show them with “#nofilter”.

The camera’s perspective projection picks just one of many ways to arrange objects in the frame. As an artist, one can choose to draw each object with any color, to make them brighter or darker relative to each other, to make some objects bigger or some smaller than each other, or to eliminate some entirely. When I paint a picture from life, those choices are intertwined in each brush stroke, which the collection of strokes together determine the shapes and color I’m using to portray objects, whether or not I’ve consciously made these decisions. Few of these decisions are conscious, whether in painting or photography; often there are a few conscious choices, and the rest arise from a combination of intuitions and technology.

Painting from photographs

To illustrate the choices involved, it’s worth comparing painting from life, versus photographs, versus painting from photographs.

Personally, I rarely enjoy painting from photographs because I feel like so many decisions have already been made in the photo. When I paint from life, I am bombarded by sensations of the world, and I must begin from those sensations to make a picture, to choose an arrangement of objects in the picture frame, and to pick their colors. In a photograph, the objects have already been arranged into a picture frame, and their colors decided. It’s hard to paint from a photograph without just copying many of those decisions.

As a result, I often find the drawings I make from life more lively and satisyfing than the ones made from photographs.

Here are four iPad sketches I made in sequence, while watching a sunset over Seal Rocks:

Each image took about 5-10 minutes to draw. For comparison, here’s a photograph that I took around the time of the second sketch:

The photo looks much more realistic, but I don’t feel like it quite captures the vibrance of the colors and the sunset. In each drawing I made different choices that are quite different from those made in the photo.

Back home that night, I drew another picture, working from a photograph taken earlier that day. This took about 30-60 minutes:

I think the colors and details here are much more realistic than in the sketches above, but that’s because I worked directly from a photograph, rather than sketching from life. So many of the color and perspective choices were made when the photograph was taken, and I only adapted them in the painting.

In fact, if you look at the photograph I worked from, it should be apparent how many of the choices in my painting came from the photo:

One certainly can start from a photograph and create something new that’s very different and new. But it’s very different than starting from life. You begin with the choices in the photograph, and then either accept or modify them. It’s like anchoring. I don’t think I would have come up with those first four sketches if I’d started from photographs.

I’m not saying that any of these images is intrinsically better than another. I think the photographs do a better job of “looking real” and conveying what the scene looks like. I think the drawings are more “expressive” and I like them better. I don’t expect that anyone else likes them. But that’s all beside the point; the main point is that these images all reflect different kinds of choices one can make.

Vision is Interpretation, Art is Construction

People who haven’t thought much about vision often think it’s easy. If you see a teapot, you know it’s a teapot. How? When asked, people give various “folk theories,” e.g., I know that it has a handle and a spout. But how do you know that that thing is a handle? Because it’s on the side of a teapot?

The long history of computer vision research shows just how hard it is to understand how vision works. In fact, many of the earliest computer vision researchers fell into the same trap. In the famous 1966 “Summer Vision Project”, a group of MIT undergrads was tasked with building an algorithm that looked at the contents of an image and describing what was in it. Now, sixty years later, and we still have not solved this problem (despite tremendous progress) that an AI professor once thought could be solved in a summer.

Nowadays, in our modern understanding of perception (which is informed by experience with computer vision), vision is about making interpretations of the stimuli we are given. Often this process is modeled with Bayesian models like predictive coding. Prior knowledge and experience provide what Gombrich called “the beholder’s share.”

When we view a picture, we know it’s a picture. We do not think we are looking through a window; numerous psychology studies show differences in how people interpret pictures of objects versus how they perceive the object itself. We can understand all kinds of artistic styles that wouldn’t make any sense if they had to be interpreted as direct recordings of light. You can basically understand what’s going on in my sunset sketches above, even though they don’t literally look like the real thing.

This is the flip side of the “art is perception” fallacy. Perception isn’t “transparent,” and neither is art. Perception is interpretation, and art is a construction made for perception.

I once drew a portrait of a friend. When I showed it to her, I mentioned that I didn’t think it was very good. She said “That’s okay, it still shows how you see me through your eyes.” This is exactly wrong. When I make a drawing, it’s not what I see, it’s what I make.

Pictures as Storytelling

Storytelling provides an excellent metaphor for making pictures. Looking at a picture is not like reading a book and knowing what the words are. It’s like reading a book and interpreting what the writer meant.

Suppose you’re at a party, or with a friend, and you want to tell a story about some complicated event in your life. You immediately have lots of choices to make. Do you begin at the first thing that happen, or start with the big event in the middle, or begin with a teasing summary? Do you describe only the external events that happened, or do you describe your feelings in the event and how you interpreted others’ feelings? Do you use neutral language or emotionally charged language? What elements do you describe and what do you leave out?

Each choice you make will affect how the listener hears the story: what they understand about what happened and about you; how they judge or interpret the events; whether they enjoy or it or get bored; and so on. It is impossible to fully convey your full experience in words. Yet we tell each other stories all the time, to communicate our experience, to find empathy and strengthen bonds, or to manipulate and persuade. The degree to which we succeed depends in part on our skills in storytelling.

Pictures are like stories. They may be pleasurable for their own sake, and they may contain information about the world and about us. But all that information is the product of choices made by the painter/storyteller. We construct stories from raw elements of experience or fiction; we construct paintings from sights and sounds and our imaginations.

Both painting and storytelling are skills that one can practice, and learn, and get better at through experience, as well as by learning various techniques (e.g., three-act structure, timing).

Drawing and painting are skills of construction, like learning languages, and learning to write. It’s not about innate talent, or just recording what you see; it’s about learning how to build images.

But Aren’t Photographs Special? Is anything true?

Photographs seem objective and real in a way that most paintings don’t. In some ways, they are. Cameras do measure light, and display it in a way that can be made repeatably and described objectively, e.g., via light sensitivity plots and color response curves. They replicate much of our experience of the real world, and “look real” in many ways. They are surely better for many tasks. If you want to know the precise shape of building, you should look at a photo and not one of my paintings. It is much easier and faster to make photographs that accurately measure aspects of the world.

Nonetheless, the way images are displayed are still the result of subjective choices, not objective truth. The difference is when these choices are made. In a photograph, many of the compositional choices were made by camera manufacturers. If you pick up a camera and shoot, then nearly all of the representational choices come from rules set up by the manufacturer. If you adjust camera settings (zoom, exposure, lenses, etc.) then you gain more control, within the array of options designed by the manufacturer.

Photographs can be very deceptive, e.g., misleading uses of forced perspective. These topics come up a lot in discussion of “fake news” and digital forgeries. See Frédo Durand’s slides for a comprehensive survey of real and fake imagery, and the confusing and fascinating ethical boundaries between them. It’s not as simple as “real” and “fake”

What is a picture?

Pictures defy simple explanation. Past psychologists and philosophers have proposed all sorts of glib ways to understand images: some have argued they are purely a cultural construct, others have claimed they are a an objective science of optics. Understanding how pictures work is far more complicated than this; they are a complex product of culture, biology, optics, evolution, and personal experience. To deny any aspect of these, whether the biological basis of vision or the cultural effects of different modes of communication, is to miss some aspects of picture-making. To assume that photography is something set apart from painting and drawing is to mistake the nature of photography.

Vision and perception play important roles in picturemaking, but each picture we make is an act of construction, an act of creation, an act of deliberate communication. Just like a story, a picture can be truthful or deceptive or creative or imaginative—or even all of these things all at once.