Why Industry Research Labs Should Publish

This post is about a question that often comes up in industrial research: why should research labs publish papers? That is, why do labs benefit from publication?

I believe there are many good reasons for this, and they are not immediately obvious.

Labs and researchers should understand why they publish because it affects how publications—and researchers—are valued, how they explain the value of their work, and, sometimes, whether things get published at all. I’ve been thinking about this recently after thinking about the open-ended nature of research and creativity.

Publication sometimes baffles corporate management. I still remember the lawyer at one company many years ago who balked at the idea that, as he put it, we’d just invented something and immediately wanted to tell all of our competitors.

Advanced research and development focused on a singular goal, like literally putting a person on the moon, can work without publishing. But many labs aren’t focused on moonshots; none of the research labs I’ve been at were operated like that, even when I was at Pixar. Not everything must be published. But publication plays an important role in many broad classes of industry research.

This post expresses my own personal opinions, not those of any organizations.

It’s hard to have basic research in industry

Industrial research is often presented idealistically, and many researchers are motivated by academic research, publication, and discovering new knowledge. But corporations run research labs in order to improve company’s profit. When done well, industrial research can be enormously beneficial, both directly to the company, and, in the publication of new knowledge, to society.

For example, Claude Shannon was an oddball who spent much of his time at Bell Labs exploring random thoughts, building strange contraptions, and juggling on his unicycle. The outcome of some of his philosophical musings, the 1948 paper “A Mathematical Theory of Communication”, transformed the world (and his employer’s telecommunications business). William Whyte’s influential analysis attributed the success of research at Bell Labs and General Electric to the fact that “Of all corporation research groups these are the two precisely that believe in ‘idle curiosity.’”

Producing high-quality long-term research while also showing corporate benefits is a tightrope balancing act. Most industry R&D is very applied, more “D” than “R”.

But labs that focus too much on short-term deliverables can’t really do much long-term innovation. If every project has to ship in a product, there’s no room for big-picture thinking, risk-taking, or exploratory research.

On the other hand, some labs veer too far into pure research, which can be great for researchers publishing new stuff, but it’s not long-term sustainable. Once the company hits hard times and managers need to cut costs, the lab gets decimated or reorg-ed into a shell of its former self.

The most famous example is Xerox PARC, which did so much revolutionary research that never got used by Xerox. In one famous story, PARC inventors demonstrated prototypes of the first personal computer with a GUI and a mouse to Xerox’s managers. Xerox’s managers didn’t see the point of any of this, saying, “My secretary doesn’t need a better typewriter.” Besides, they were in the business of selling photocopiers. Then, Steve Jobs saw these demos, and adopted them all in the Apple Macintosh.

Some subsequent labs tried to be “Xerox PARC, but successful.” I worked at one of these, Interval Research, as a summer intern with Trevor Darrell in 1998. Interval’s management told researchers “if you’re doing research that’s less than 10 years to commercialization, then you’re thinking too short-term.” Indeed, during my summer there, I saw so many inspiring, moonshot-level internal project presentations and met so many creative and talented researchers and artists. But the lab closed down after only 8 years in existence, with very little to show for all that time and money.

Why is this balance so hard to reach? The best research is often open-ended and exploratory. You have an idea, you try it out and see what you find. You cannot plan this kind of research; you cannot tell if it will be useful; you do not know whether or not anyone in the company will ever want it. Maybe a project won’t be useful but it will lead to a different one that is. Occasionally you start with one very focused goal and end up with something totally different—and more interesting than the original goal.

We can call this The Paradox of Open-Ended Research: research that is not focused on a specific, static goal often has the most impact and benefit. It can be more impactful than research that formulates a strict plan and sticks to that plan. Consequently, it’s impossible to know in advance which projects are really going to show a benefit, and, conversely, there is lot of research performed that is generally not useful. Complaining that most papers aren’t useful completely misunderstands research.

This means that

Conversely, expecting rigid, predictable evaluations prevents high-quality research from happening.

In the words of Albert Einstein, “If we knew what it is we were doing, it would not be called research.”

And so there is an art to managing such research. It is a struggle to balance long-term, open-ended research and short-term impact, valuing publications on their own without becoming a paper mill, or, conversely, neglecting long-term benefits for short-term deliverables.

And, preserving the balance requires continued vigilance.

Why publishing is valuable to industry labs

In my opinion, the most important reason to publish is:

Publication can help in all stages of research, from motivating better work to getting feedback on it.

Of course, a lab that churns out lots of papers might not produce anything useful other than long CVs. Publication is a tool to improve research; it is not the end goal in itself.

As an alternative, consider a whitepaper model: instead of publishing papers externally, researchers write whitepapers or technical reports, and share them in some company-only repository or Wiki. I argue that the whitepaper model (or any variant of it) will, on average, produce much worse research.

Here are some specific ways in which publication helps.

1. As a recruiting and incentive tool

One common justification for publication is: it’s a recruiting tool. In order to hire and retain the best researchers, you let them publish.

This is indeed a good reason to publish. Speaking for myself, publishing new research is very important to me, and, I think, to many other researchers.

However, treating publication as merely an employee benefit—like vacation time and breakroom snacks—is a big mistake. Publication should not be something that researchers are “allowed” to do in, separate from their “real work.” It should be considered a major part of their real work.

2. To provide motivation, milestones, and standards

During the process of a research project, you have many questions to answer. What are the long-term goals of the project, and how can we break down those goals into shorter-term milestones? How hard should we work on it? What demos should we build? How do we evaluate it, and how do we know how well it works? How should we document the project?

Paper publication helps with all of these questions.

In the whitepaper model, researchers can develop uninteresting, incremental projects and make whitepapers. Or they can spend years chasing a big problem, with nothing to show for it years later—this definitely happened at Interval. Or they might have a good idea but not evaluate it deeply enough to understand when it does or doesn’t work. Or they might develop something very cool and then fail to document it clearly; writing clearly is exceedingly difficult, and people often don’t know when their writing is unclear. There’s just not much immediate motivation to work any harder if your output is going to a PDF stored on a server that no one reads. And, even for the sincerely motivated research, there’s not much limited feedback as to whether they’ve done well, and how to improve.

Conversely, it’s simply hard for researchers to know if their work is any good. It is easy for us researchers to delude ourselves into thinking our work is great if we don’t have to convince anyone else about it. Researchers often hate peer review because the reviewers don’t believe the work is as great as the authors do. Publication provides some bare-minimum standards.

Publishing a paper is a potentially a lot more work than writing a whitepaper, and, again, just because something’s published doesn’t mean it’s good. Everyone knows that peer-reviewed publication models have many flaws and biases, e.g., incrementalism, overreliance on onerous evaluations. But, used well, publication really helps motivate and refine ideas. Sometimes just the existence of an external deadline makes a huge difference.

3. To support internal communication and discovery

Another seeming paradox of research is that, sometimes, the best way to share information internally is to share information externally.

The development of the Microsoft Kinect software provides a key lesson. The story I heard began with a Microsoft VP, who, around 2006, envisioned an interactive gaming system that didn’t require controllers. His team used the PrimeSense sensor, which allowed real-time depth measurements. But they couldn’t figure out how to reliably estimate human body pose. So they started looking around online for papers on pose estimation. They noticed that some of the best papers on this topic listed the affiliation “Microsoft Research.”

And so, external publications was how some Microsoft engineers discovered that the world’s top experts on their problem worked at the same company as them. Making this connection was integral to the Kinect’s success.

Relational databases have a similar story. The original relational database paper was published in 1970 by a researcher from IBM Research, but nobody at IBM paid attention to it. Larry Ellison read the paper and founded Oracle around it. IBM then realized they could compete, and built their own relational database system called Db2 that ended up being very profitable. This only happened because of the publication of that paper.

An underlying theme here is: communication in an organization is hard. Figuring out how to connect researchers with engineers that need their expertise is a shockingly-difficult organizational problem.

It doesn’t seem like it should be hard. Researchers should make databases on what they’re working on! Product teams can then look in the databases to find what they need! But filling out and sorting through a database is unrewarding and frustrating for everyone. The whitepaper model would have completely failed the Kinect. Researchers can have show-and-tell meetings with product groups! But still one must figure out which researchers should meet with which groups, and which research they should show.

Only rarely does a paper directly solve the real problem that product teams have; research projects allow researchers to build expertise that they can use to help product teams. You can’t really tell from a database of whitepapers who really knows what.

4. To get feedback from the research community

Suppose you wanted detailed feedback on a project from academic experts. How much would it cost? How hard would it be to recruit them?

It would be expensive, at least. But, most likely, they wouldn’t respond at all to most requests.

With publication, in exchange for sharing your work with the world, you get this feedback for free. Sometimes the feedback isn’t great, but often it’s really valuable.

Often the feedback doesn’t feel great, but part of the art of reading reviews is in reading between the lines. Doing so to understand the fundamental issues can be really valuable.

I can think of several times when reviewer feedback has really strengthened my work. We submitted a paper to SIGGRAPH 2004 that was rejected, even though we were really proud of it. One of the reasons for rejection was a very hacky treatment of center-of-mass forces, which we thought inessential to our ideas. But we fixed that hack, and the revised version was accepted the next year. The new version was far better without this hack.

I am forever indebted to that anonymous reviewer several years ago who, in the process of rejecting my half-baked submission to an art journal, pointed me to Rob Pepperell’s work, which in turn led me to publications in both indeterminacy and perspective in the years since.

Once you publish the paper, you can get more feedback: feedback from conference-goers, feedback from social media. People may make suggestions—or use your work—in directions you’d never thought of.

5. For researcher evaluation

Having researchers publish gives a sense of how their research is doing, especially if their work gets extra recognition or leads to invitations and awards.

This has the obvious pitfalls: researchers shouldn’t be evaluated by paper counting, and a company that purely incentivizes submissions puts an undue burden on the research community.

6. To stay engaged with the community

Research is a community, or, rather, a set of communities. Participation comes from publishing, reviewing, serving on communities, giving talks, chairing conferences and journals, writing reference letters, mentoring junior researchers, and attending conferences and other meetings. Much of this is service to the academic community.

Industry researchers who participate deeply in the community become part of the community, building valuable social relationships that allow them to keep their finger on the pulse of research and to recruit. Conversely, industry researchers and developers that do not participate may be seen as only taking from academia and not giving back. Industry labs are often seen positively or negatively by academia by how much they support or give back to the community.

7. To inspire research in areas the company cares about

Publishing research in an area can inspire outside researchers to work on things the company cares about. I’ve heard stories of this working well.

8. Flag planting

I’ve heard that publication can help defend against certain kinds of frivolous lawsuits, since they demonstrate publicly that you had a specific idea at by a specific time, so other people shouldn’t be able to later patent that idea and sue you for infringement.

Finding the Balance

There is no single, simple recipe for successful research: open-ended exploration by nature is an exploration. When used well, publication is a tool that helps researchers do better research. When used badly, publication becomes the only goal in itself, driving publishable but useless research. Likewise, there is no single, simple recipe for managing research; truly measuring long-term impact with short-term metrics (like publication counts) is impossible.

Every successful industry research lab lies in an unstable equilibrium between the two main pitfalls: research solely for the sake of research without corporate benefit (which is unsustainable), or short-term research that must show corporate benefit (which kills long-term innovation).

Doing great research is an art, and managing great research is an art as well.

A few other interesting readings:

-

The Rise and Fall of Industry Research Labs by Moshe Vardi.

-

The Idea Factory by Jon Gertner, about the history of Bell Labs (via Omer Shapira).

-

A recent take from an ex-Google Brain employee with some different points from those here.

-

Craig Reynolds recommends the book Fumbling the Future: How Xerox Invented, then Ignored, the First Personal Computer

-

Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned with many great examples of open-ended discoveries (although I disagree with their framing that “there is no objective”)

-

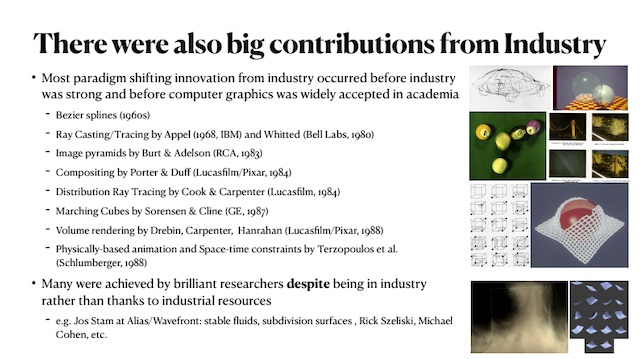

Frédo Durand’s slides on whether academia can compete with industry, which includes this slide about important academic contributions from industry in early computer graphics:

Thanks to Vova Kim, Craig Reynolds, David Salesin, and Moshe Vardi for several comments and suggestions.